Atlas

Jar Of Sparks . October 2022 - January 2025

Dread was a single player game in development from January 2023-August 2024.

Atlas was a coop PVE experience in Development from September 2024-January 2025.

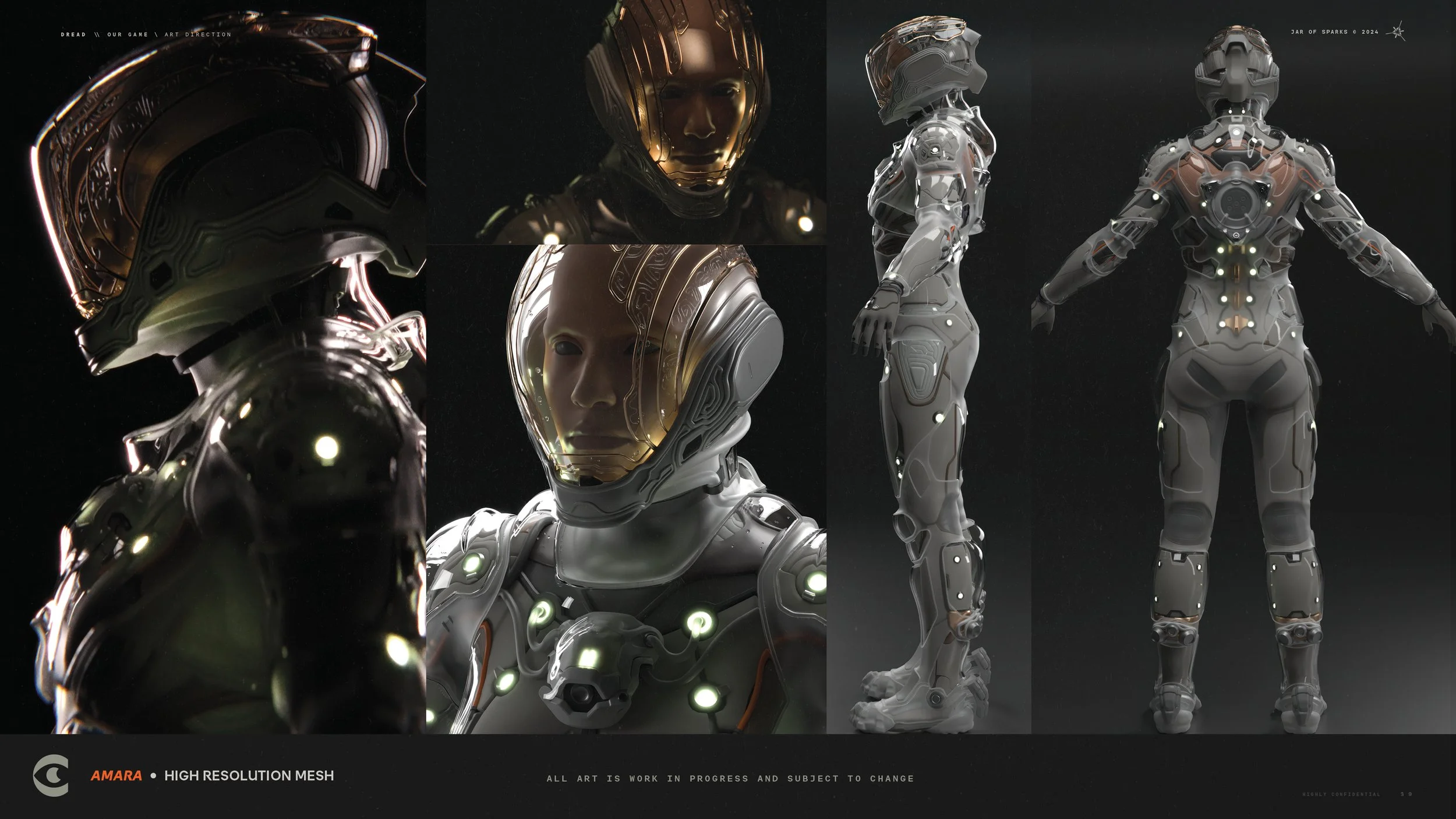

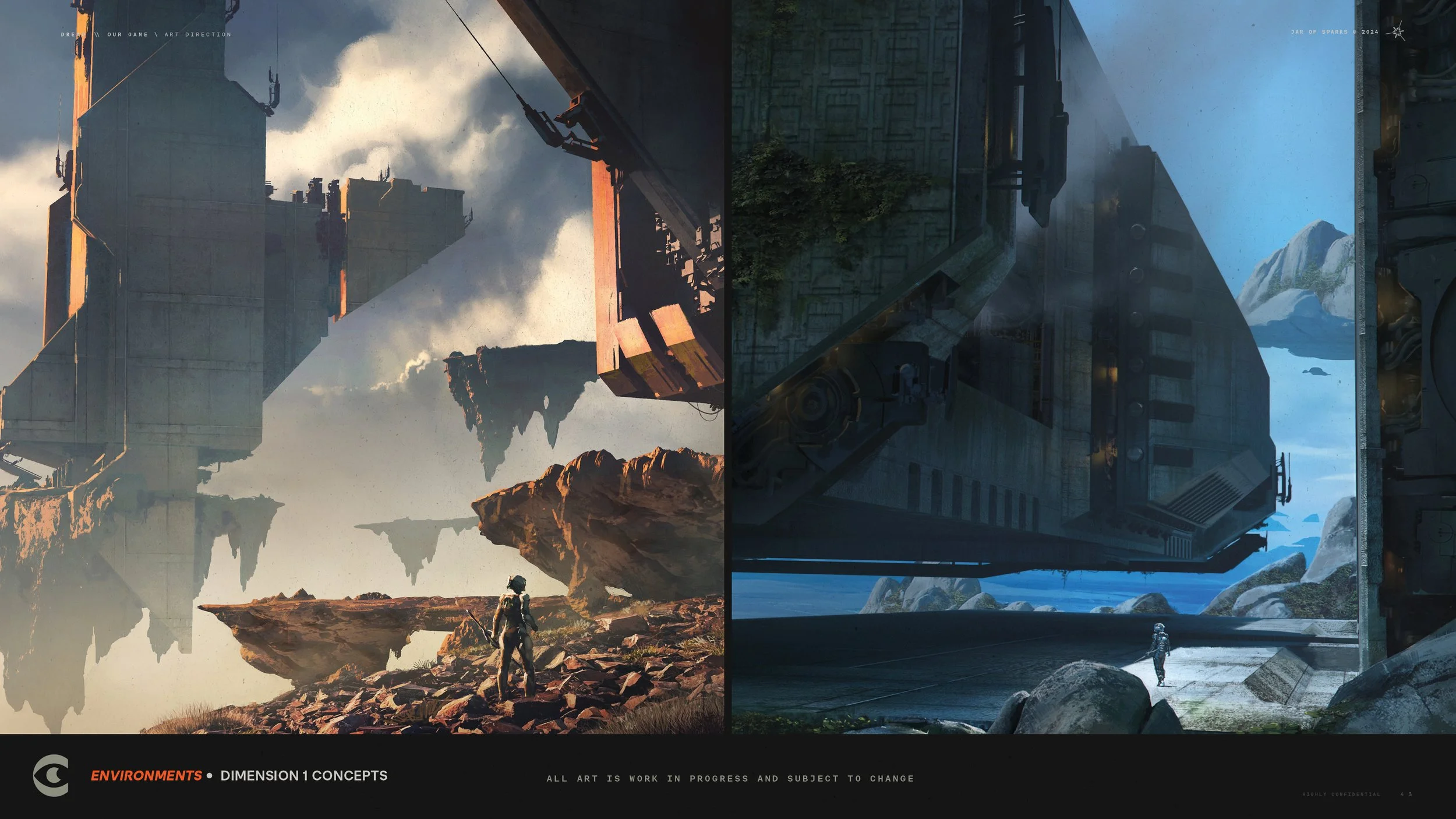

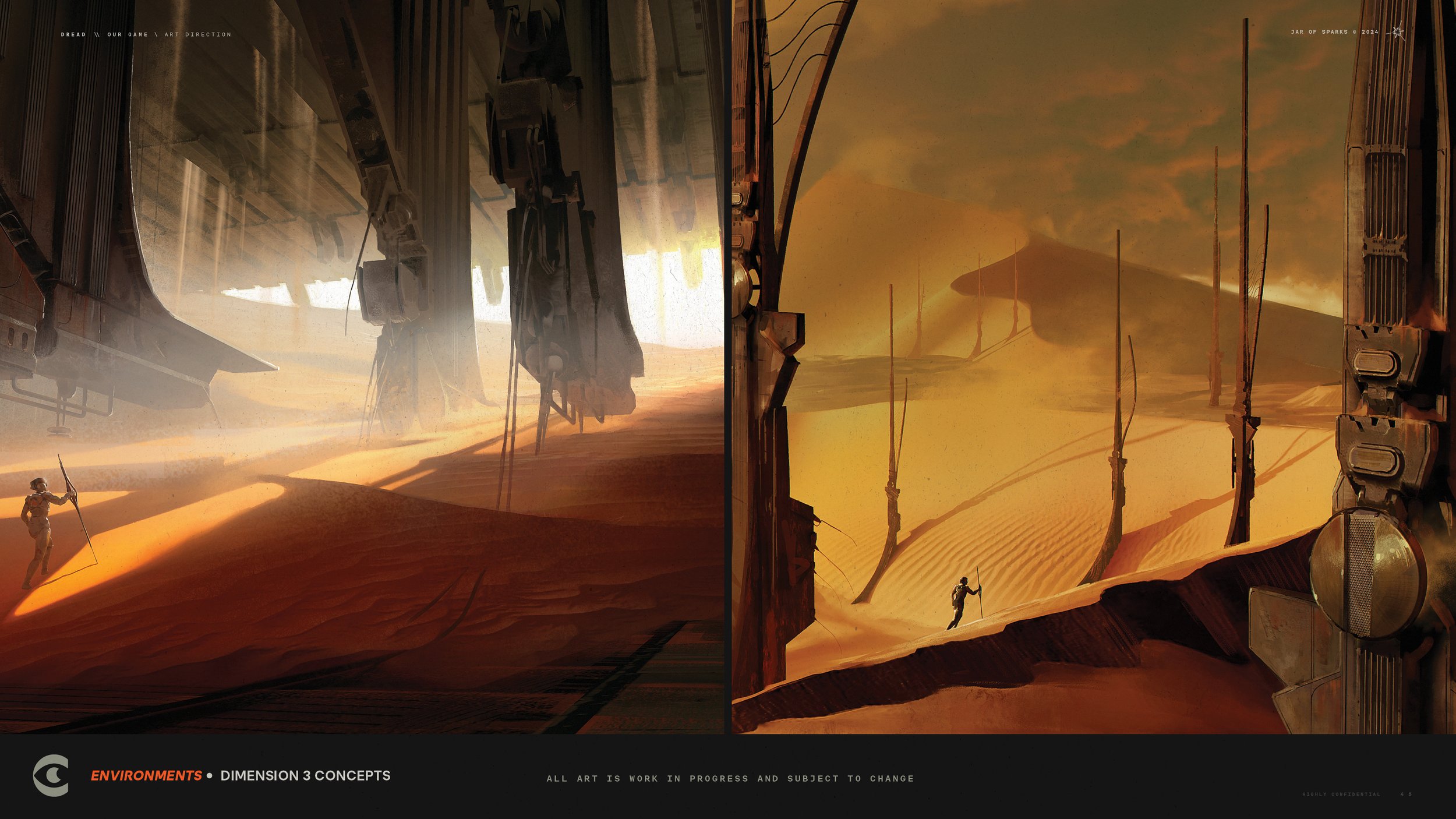

Atlas/Dread was a game that was in development for 2 years at NetEase. The link posted above is one of our last creations. It was a coop PVE experience that was created from the ashes of a single player game called Dread. That video was part of a Q4 2024 pitch deck to enter the vertical slice phase of development for NetEase. Please note that nearly all of the environmental concept art here was made by Martin Dechambault and the character concept art was made by Jeff Simpson. There were many other artists too and absolutely no AI was used in the creation of Dread or Atlas.

Origins

In April 2022, my former Xbox manager, Jerry Hook, approached me about becoming a founding member of a new studio. After a few initial discussions, I declined and chose to stay at Microsoft.

About five months later, their Creative Director reached out again and the project they were considering had evolved in scope. This time, I was offered the opportunity to create new worlds, with the promise and goal of building a new AAA-scale franchise. I would join as their Game Experience Director, overseeing the hour-to-hour experience of the game’s story and level design.

Dread

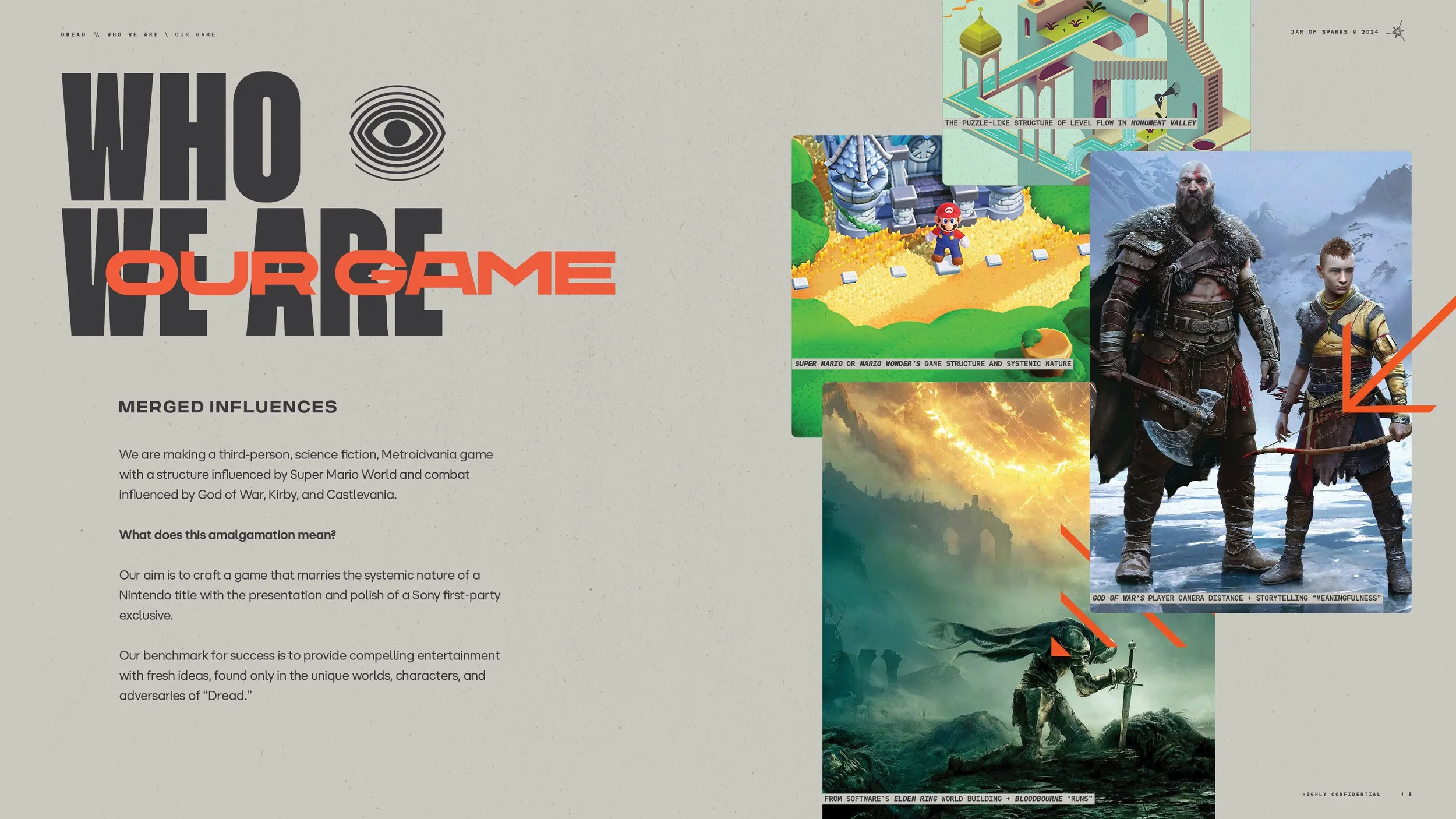

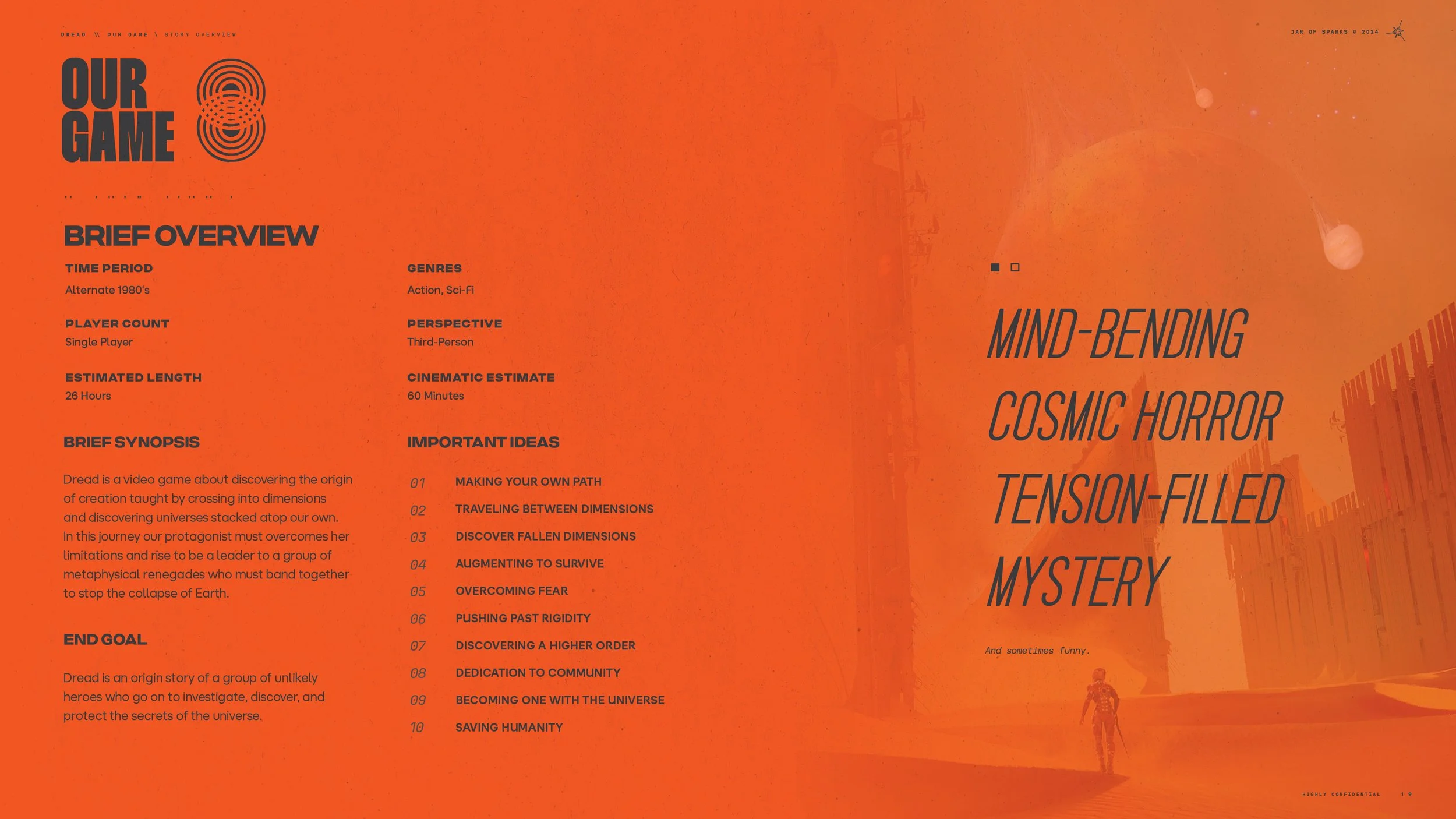

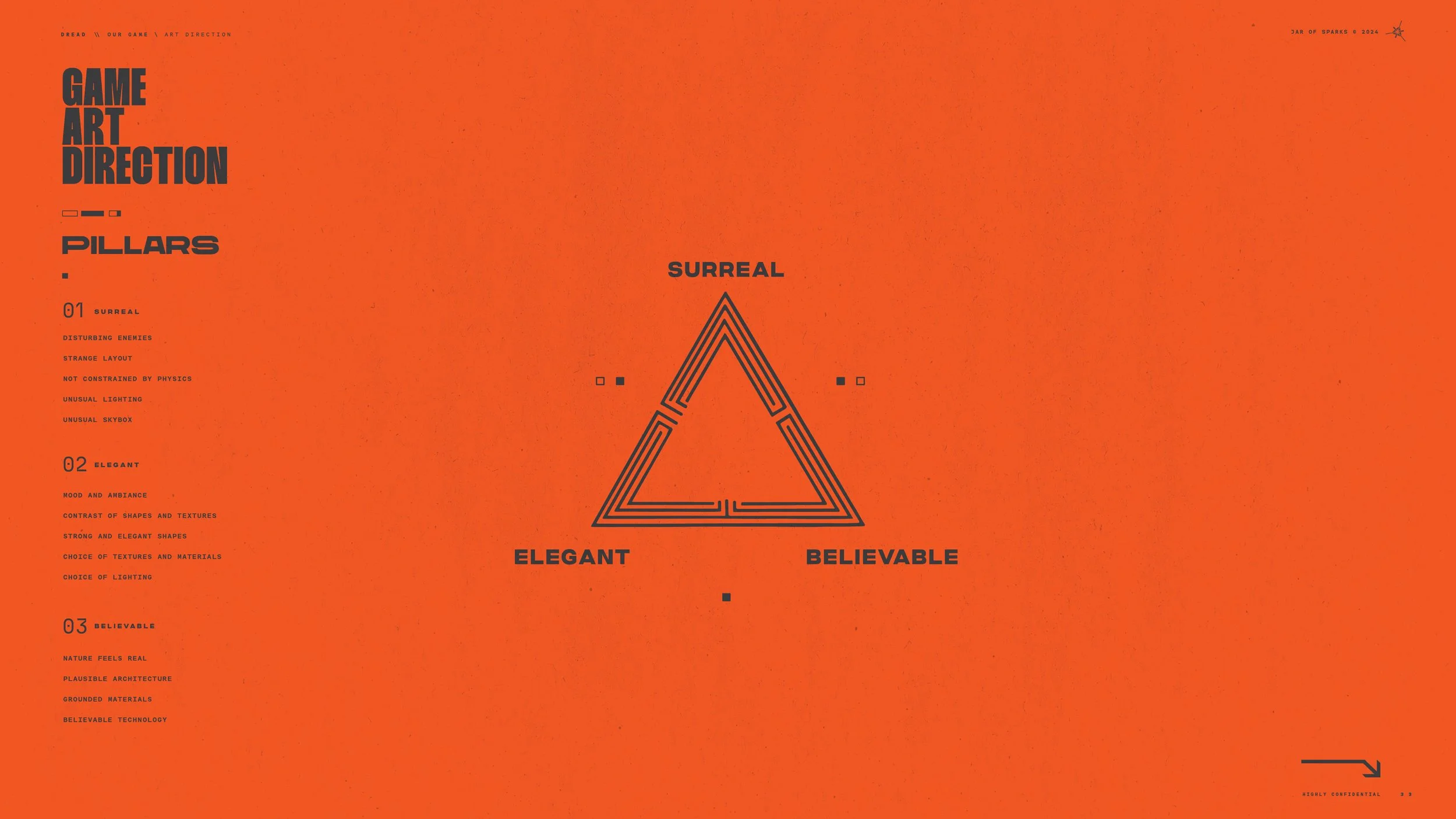

Dread was an ambitious, mind-bending science fiction adventure created by Jar of Sparks and published by NetEase. Not just another third-person action game; it was an exploration of dimensions, cosmic horror, and the human spirit’s resilience against the unknown. Designed as a Metroidvania with elements influenced by Super Mario World for its structure, God of War for its combat, and Castlevania for its sense of progression.

n a world filled with linear cinematic games and open-world sandboxes, Dread aspired to be different. It was a science fiction odyssey, a puzzle-box adventure, and a combat-driven action game all at once. It gave players freedom within a structured mystery, where every action had cosmic consequences.

At its heart, Dread was about becoming something greater than yourself—about uncovering the truth of existence, the weight of knowledge, and the cost of power.

Narrative Backdrop

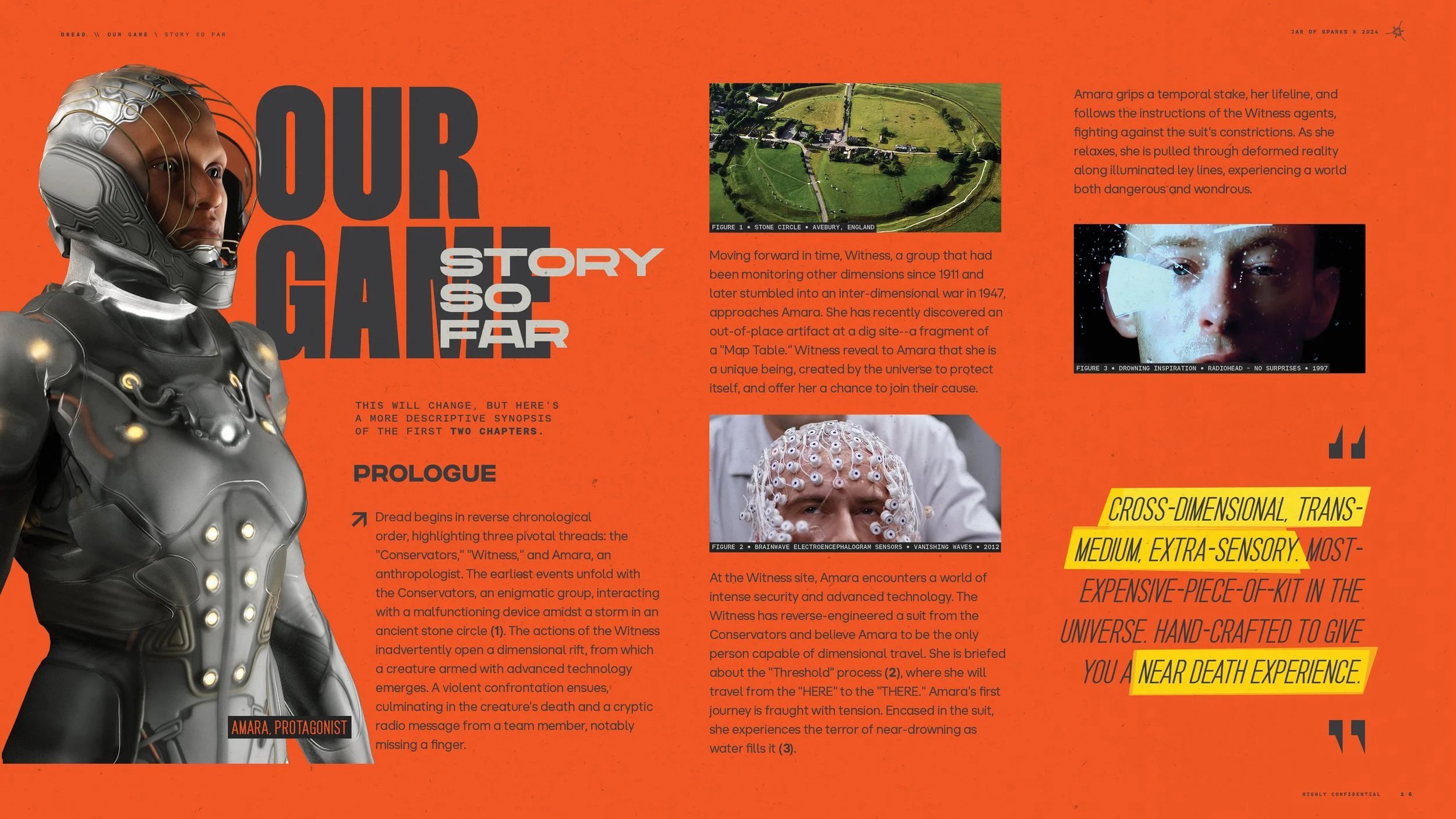

Dread is set in an alternate timeline, primarily unfolding in a version of the late 20th century, with its events branching from key discoveries made by Witness—a secretive organization that first detected dimensional anomalies in 1911 and later stumbled into an interdimensional war in 1947.

By the time Amara is recruited, Witness has developed the technology to navigate the THERE, sending operatives into fractured dimensions in a desperate bid to prevent reality from unraveling. While much of the game takes place in these surreal, collapsed worlds, its connection to Earth's history—particularly the idea that humanity was never meant to uncover the truths Witness has found.

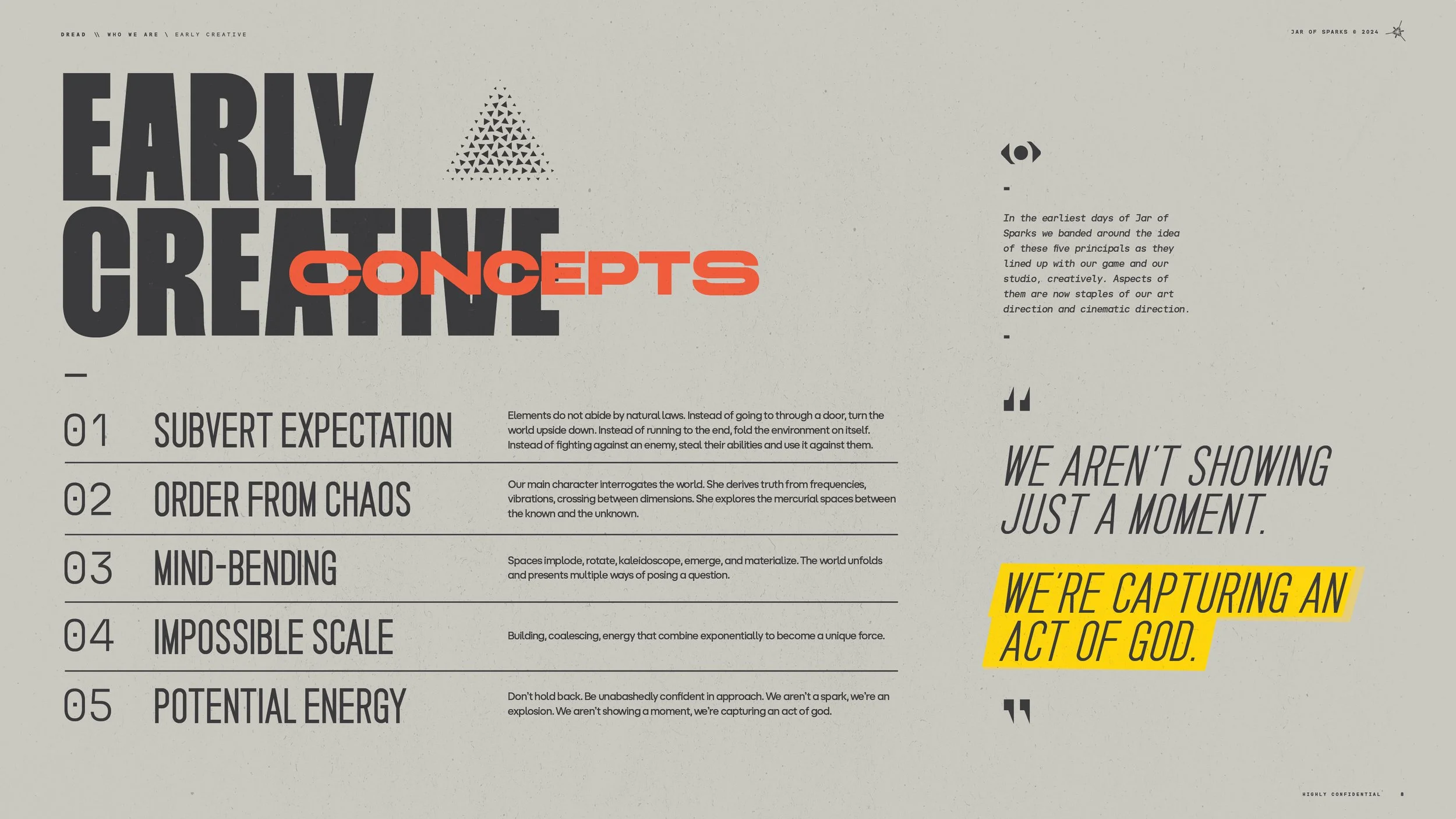

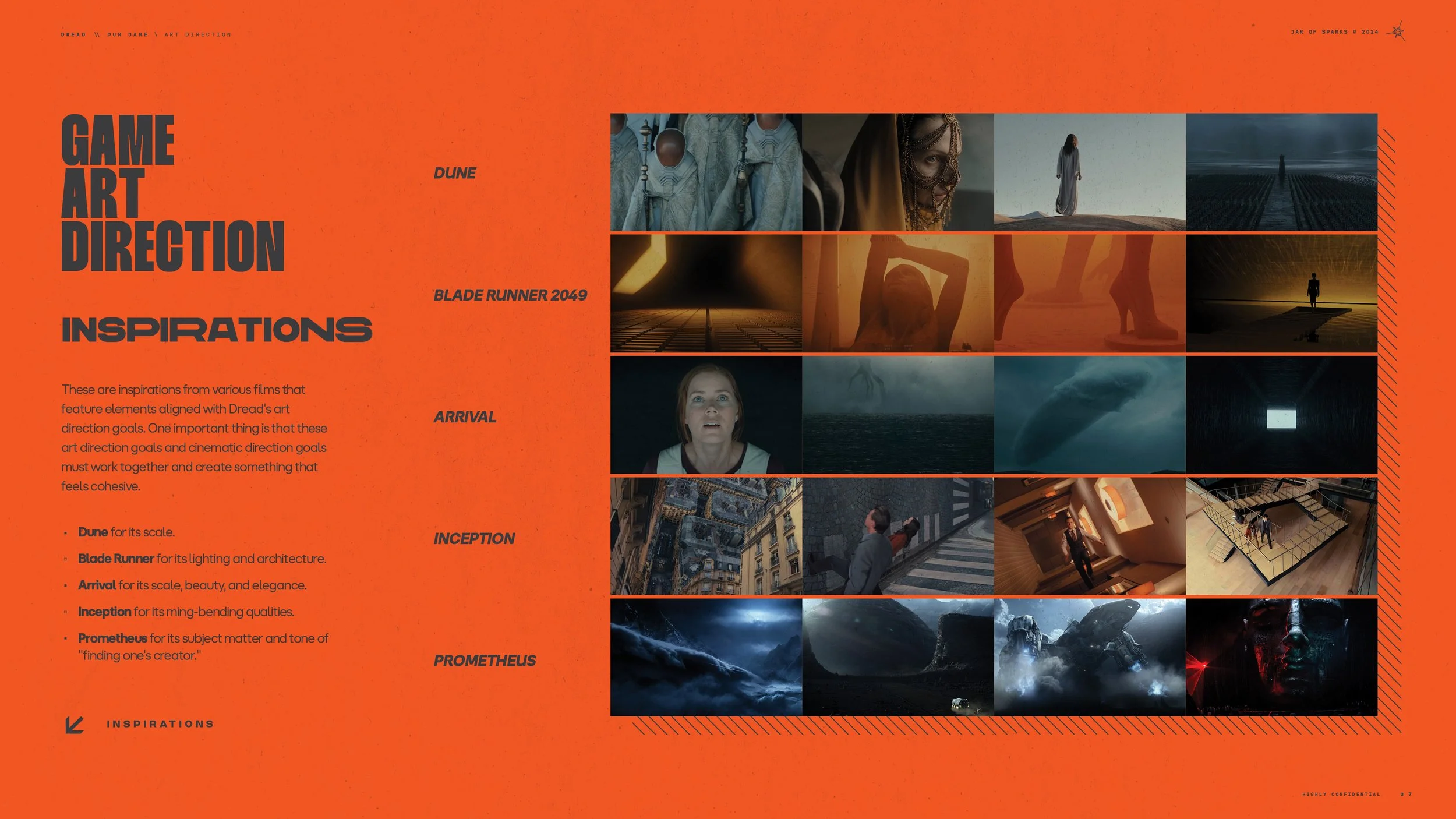

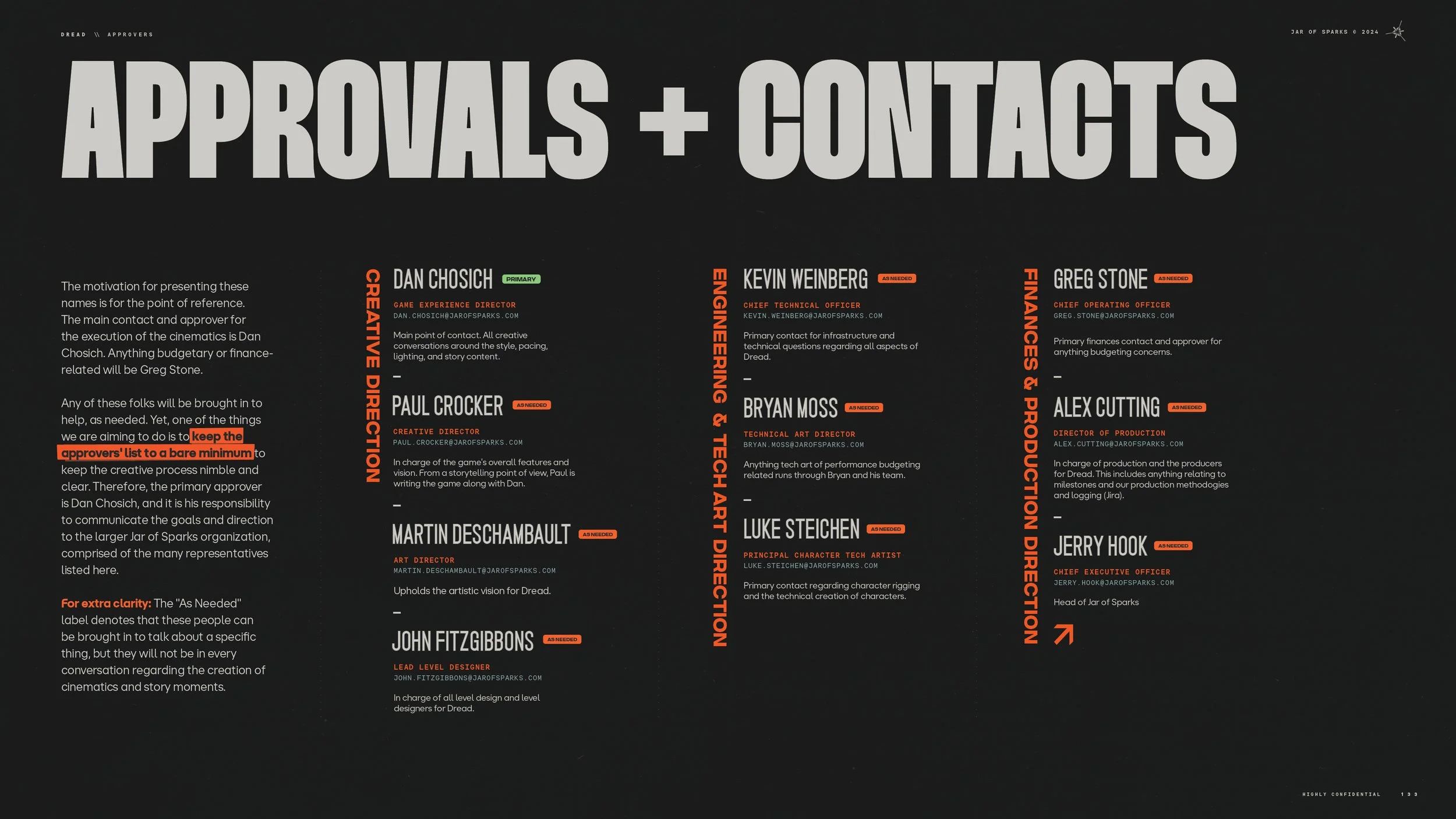

When presenting the game we were creating to NetEase, I developed materials to explain the team and various concepts of the IP. Some of these were created before the team was even hired. As a result, many film and TV references were used to help convey ideas—serving as key touch points for NetEase’s executive and marketing teams.

Atlas: Team Composition

Video showcasing the various projects the leads and directors of the project had worked on prior to joining Jar of Sparks.

Atlas: Halo Team Experience

Video to reinforce that nearly all of Halo Infinite’s campaign leadership team worked at Jar of Sparks along with various environment artists, FX artists, and combat designers.

Dread: Witness

Video to help explain Witness. Witness is a secretive, extradimensional exploration and extraction force, founded in 1854, that operates at the bleeding edge of science and the occult, tasked with uncovering the hidden history of the multiverse, salvaging lost knowledge, and preventing reality from collapsing

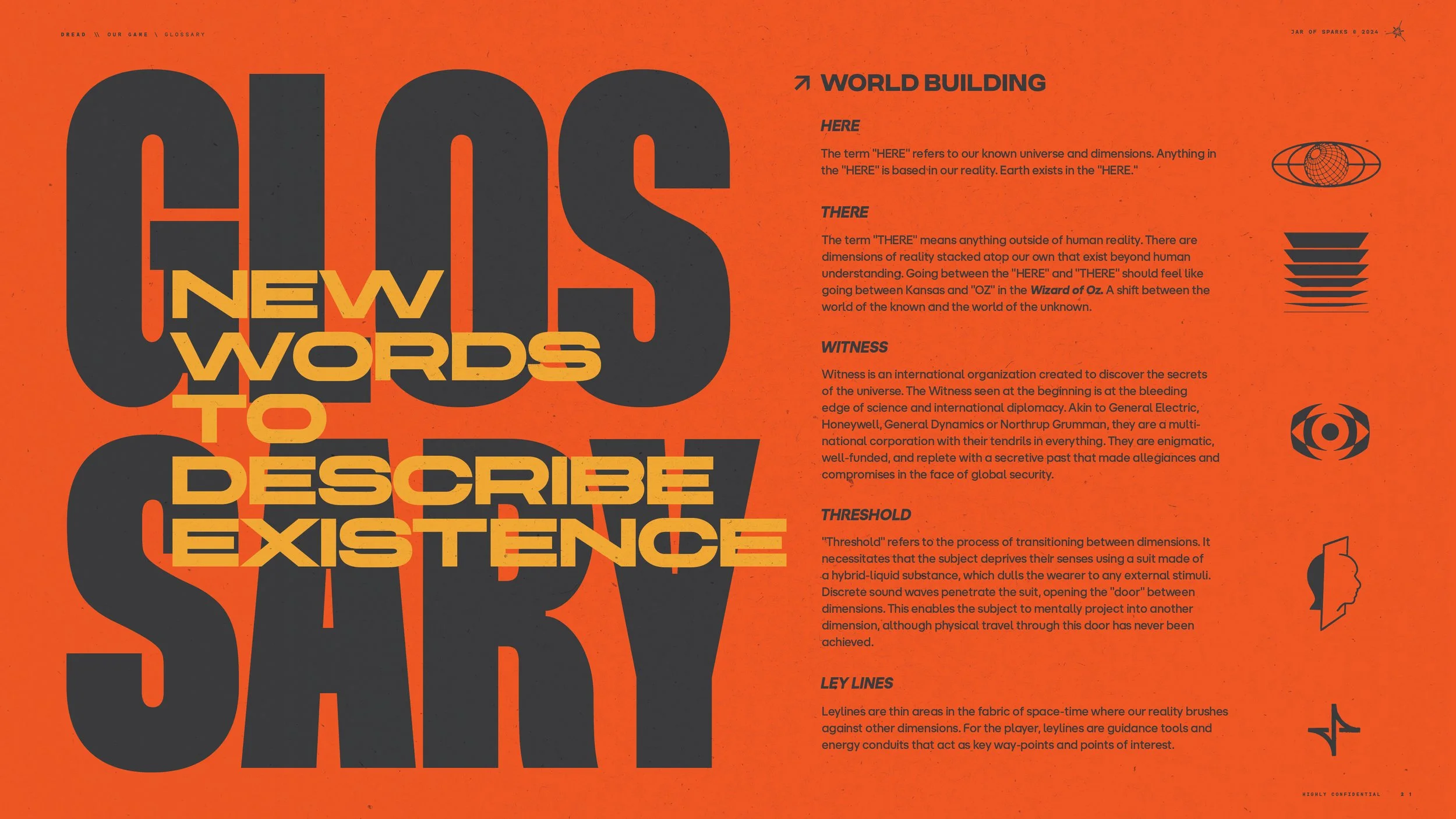

Dread: Here

Since we didn’t have a name for our reality, we referred to it as the “Here.” We wanted The Here to feel akin to Dorothy’s reality before she visits Oz—black and white, clinical, and oppressive. Despite the terrible dangers, visiting other worlds serves as a reprieve.

The “Here” is the known universe—Earth and its tangible reality—where Witness operates from, a fragile anchor of existence slowly unraveling as dimensions bleed into each other.

Dread: There

A video to explain, “The There.” This was done early in the concept phase. There was this thinking that being in “The There” was similar to rock climbing and every step forward needed to be secured similar to campfires in a FromSoft game. Definitionally, the “There” is a vast, surreal expanse of collapsed dimensions, fragmented civilizations, and cosmic anomalies where time, space, and reality itself have begun to decay.

Atlas: Enemies

This video describes the feeling we wanted the enemies to espouse. Every dimension had 4 species and inside of that species were 10 families of variants. Bosses/Gods were not included in those figures.

UNIQUE SELLING POINTS

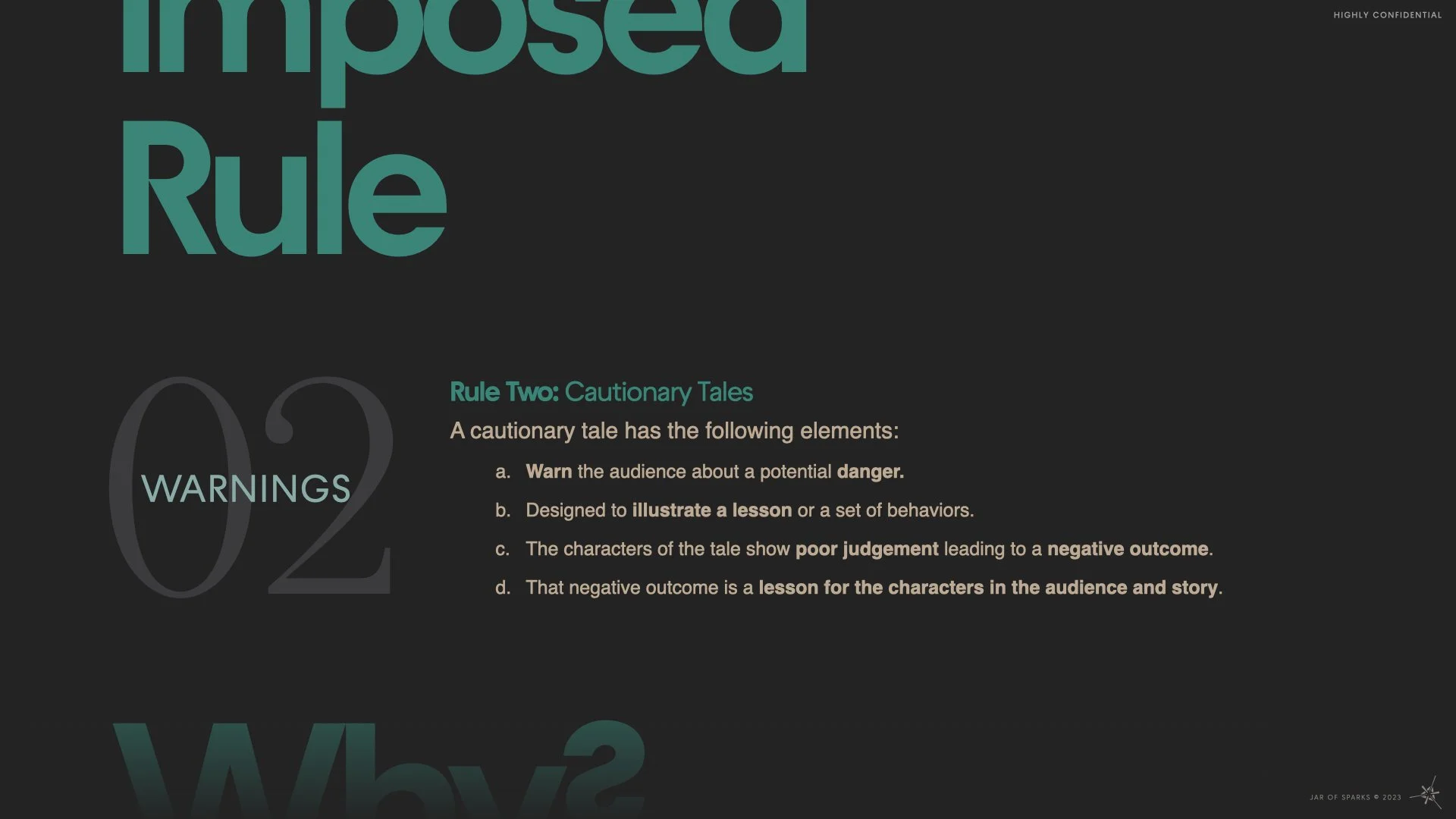

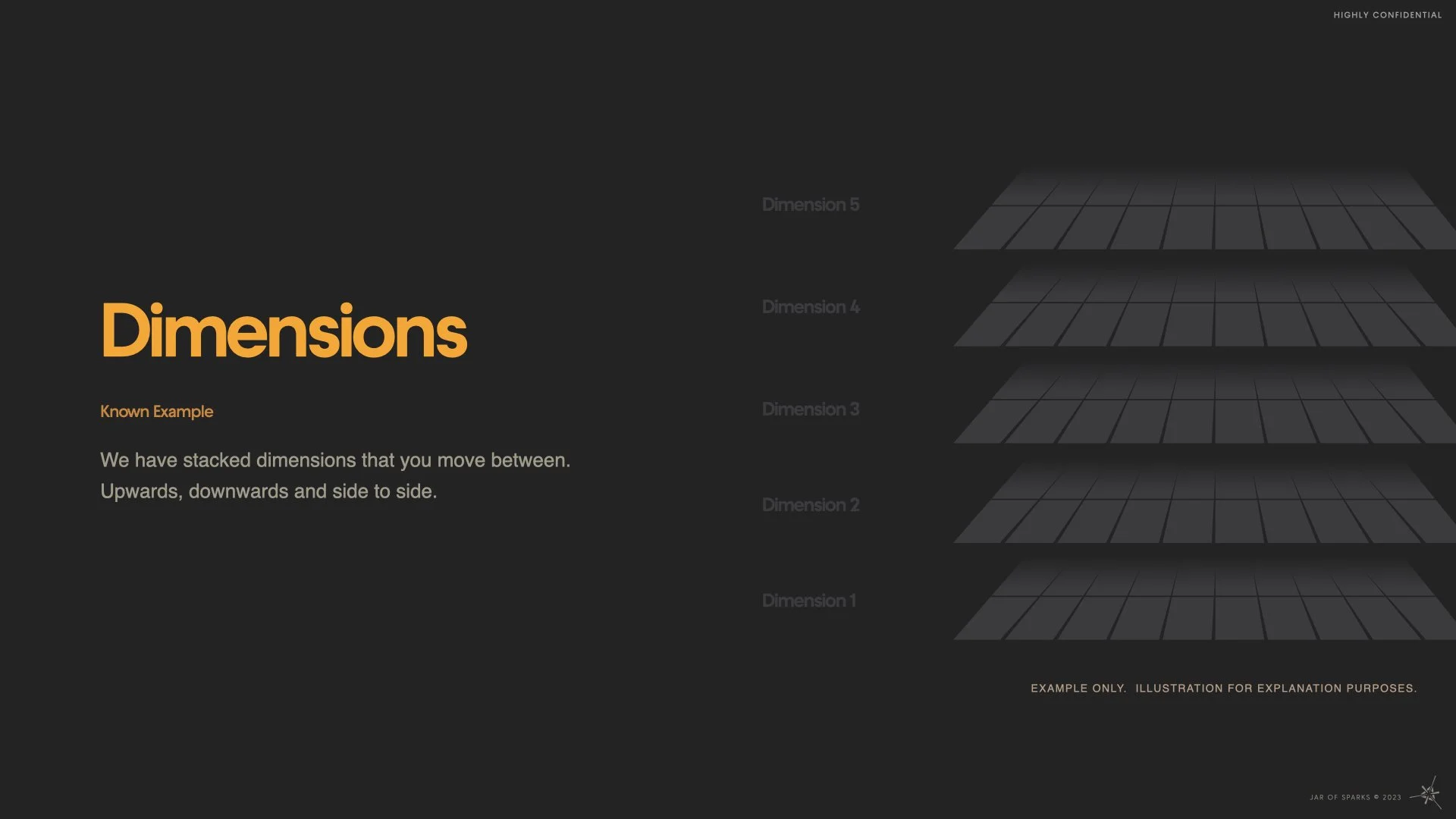

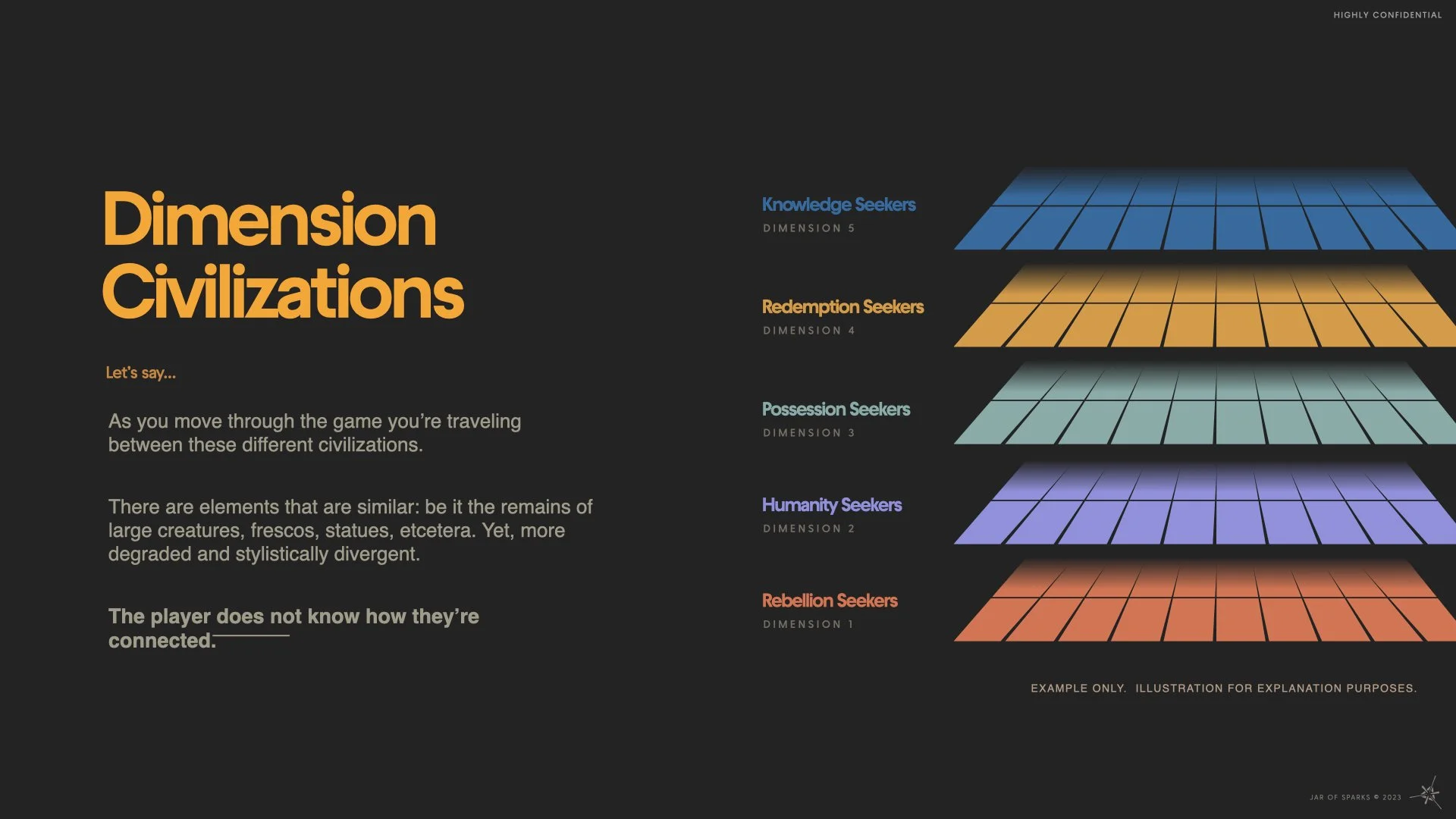

Living, Breathing, Dimensions

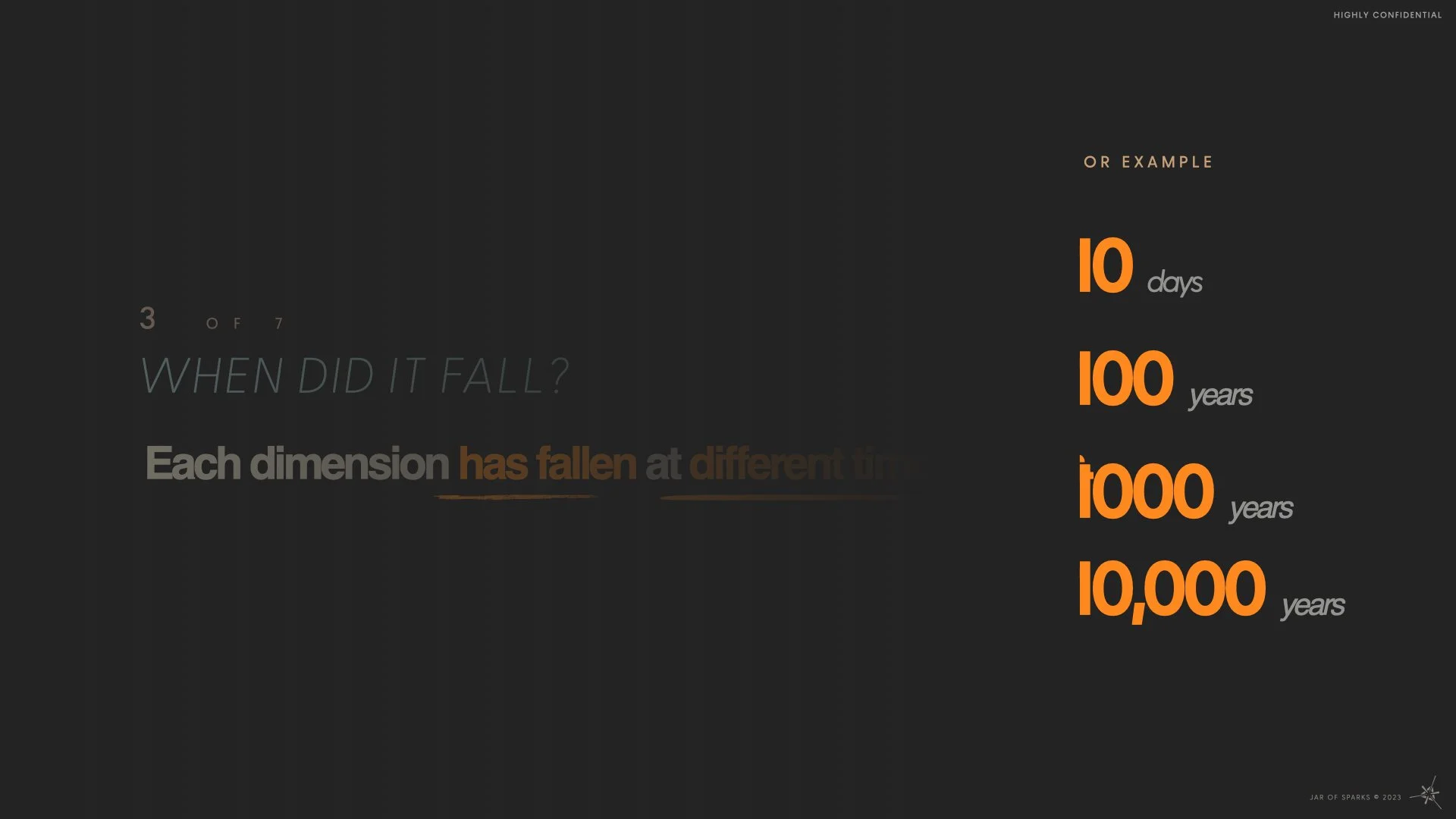

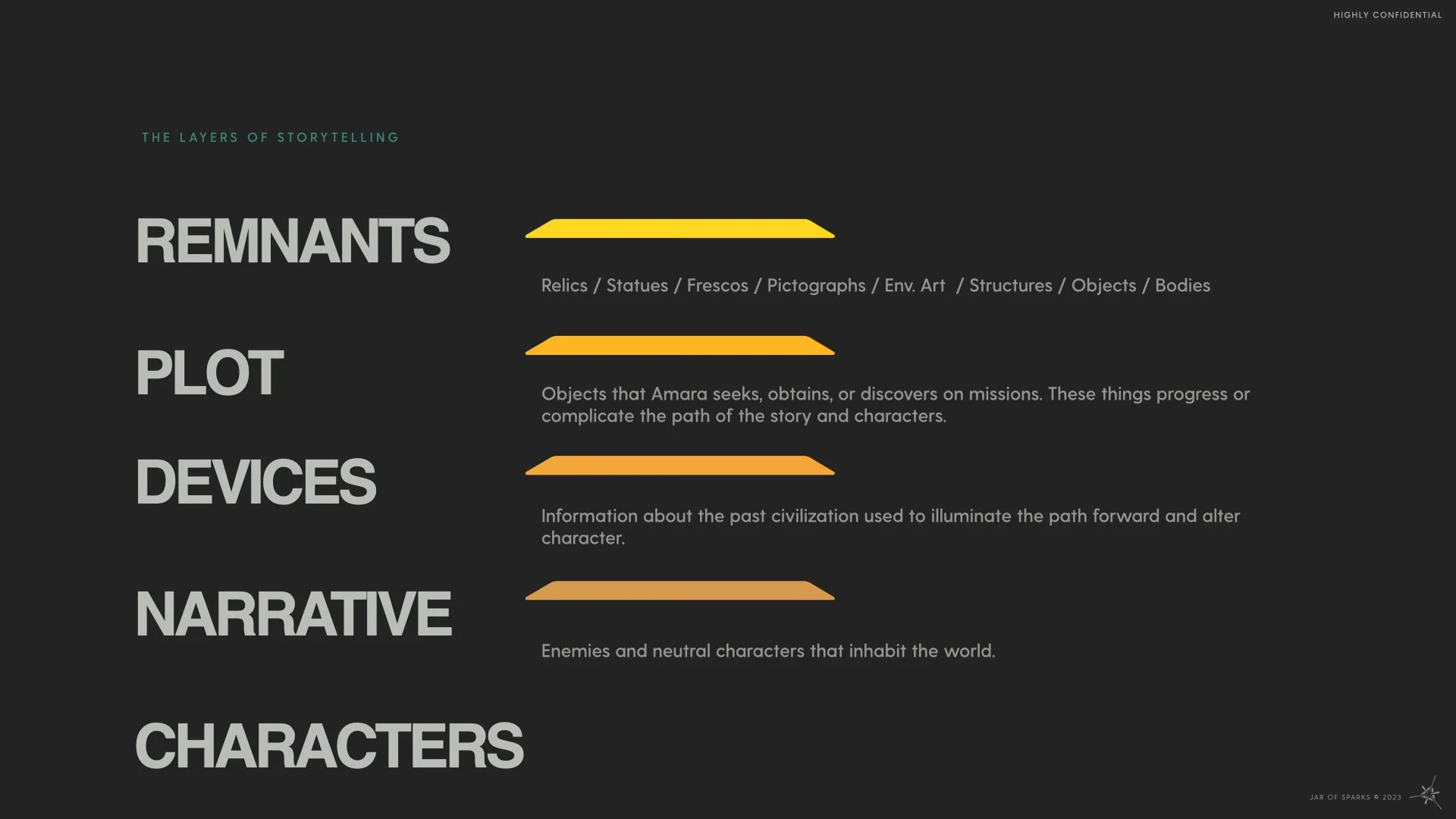

The world of Dread was not just a single setting but a network of interwoven dimensions, each with its own set of rules, histories, and perils. These dimensions were cautionary tales—failed civilizations that had reached too far, unraveling their own existence. Players navigated these broken worlds through ancient ley lines and portal technology, uncovering the remnants of lost knowledge and forbidden power.

The Map Table

The Map Table is an idea that I created with the Creative Director after a long period of trying to figure out the game’s structure. We discovered the difficult way that it’s hard to write a game if you don’t understand the way the game is structured. Figuring out the structure was the key to understanding the way the story needed to unfold.

What is The Map Table?

The Map Table was an ancient, reality-warping artifact that allowed players to manipulate dimensions, create pathways, and reshape their journey through the game. Unlike traditional game maps that merely marked locations, the Map Table dynamically altered the connections between different dimensions. By inserting missing pieces and rotating its structure, players could access new areas, uncover hidden lore, and even change the rules of engagement in each level.

How Did it Work?

The Map Table started broken, with missing pieces scattered across different dimensions.

Players had to explore worlds, solve puzzles, and survive enemies to collect these pieces.

Once pieces were inserted, new pathways appeared, ley lines connected maps, and previously unreachable locations became accessible.

Each piece of the Map Table unlocked knowledge about the universe, revealing how civilizations fell, why the Witness was so invested in Amara, and the true nature of the Conservators.

The more Amara rebuilt the Map Table, the closer she got to understanding her role in the multiverse and the existential threat looming over reality.

What Made The Map Table Unique?

Tactile & Nonlinear Design: The table wasn't just a static UI—it was an interactive, physical object that players could rotate, manipulate, and use to strategize their next move.

Dimensional Tethering: Objects and pathways could be "tethered" or "untethered" to different maps, fundamentally altering environments.

Ley Line Navigation: The table interacted with ley lines—hidden energy currents linking dimensions—which allowed Amara to discover new portals and hidden locations.

A Living Artifact: The table reacted to player choices, changing the world around Amara based on how it was assembled.

Cosmic Horror Mystery: It was implied that the Map Table had been used before, possibly to create entire universes, making it more than just a tool—it was a remnant of gods, conquerors, or something even worse.

Puzzle Box: The Map Table turned the runs into a puzzle box. Each map on the run would need a very clear landmark. Specific maps along the critical path would be designated on the Map Table with unique iconography to ground the player upon glance. The structure of the game itself became a game where players could manipulate the levels they wanted to play to gain rewards, buffs, and face enemies that granted them specifics powers to achieve longer and more advantageous expeditions.

Cautionary Tales & Cosmic Guardians

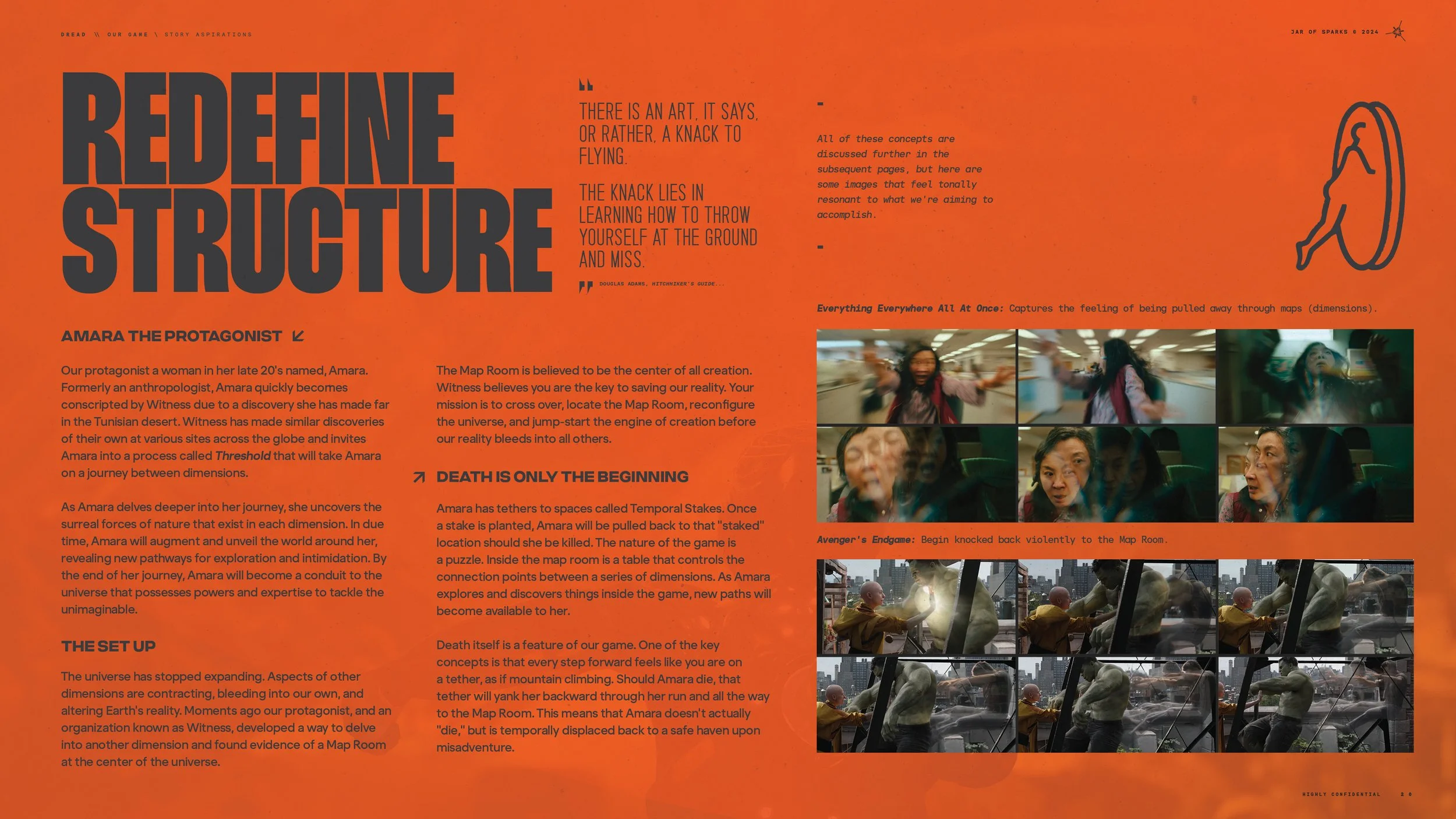

At the heart of Dread was Amara, an anthropologist turned interdimensional explorer, who stumbled upon an artifact—the Map Table—that thrust her into the unknown. Amara's journey was as much about self-discovery as it was about cosmic mysteries. She learned that she was not the first to traverse the THERE—a liminal space between realities—but part of a greater lineage of explorers and protectors.

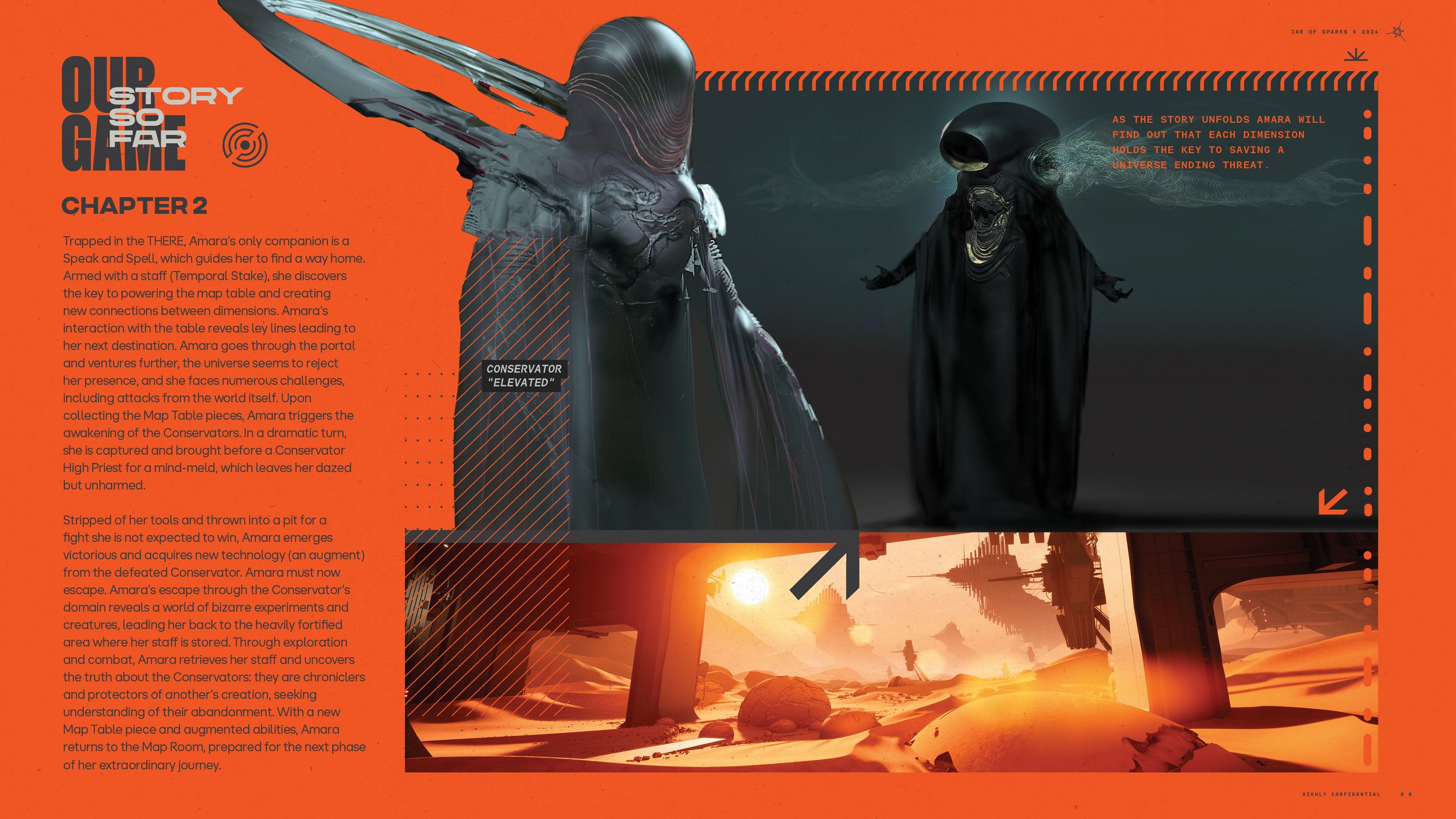

The Conservators, enigmatic beings designed to safeguard knowledge, had long abandoned their creators' laws, seeking to transcend their existence through forbidden experimentation. Meanwhile, the Watchers, colossal extradimensional enforcers, acted as reality’s immune system, hunting those who tampered with the balance of the universe.

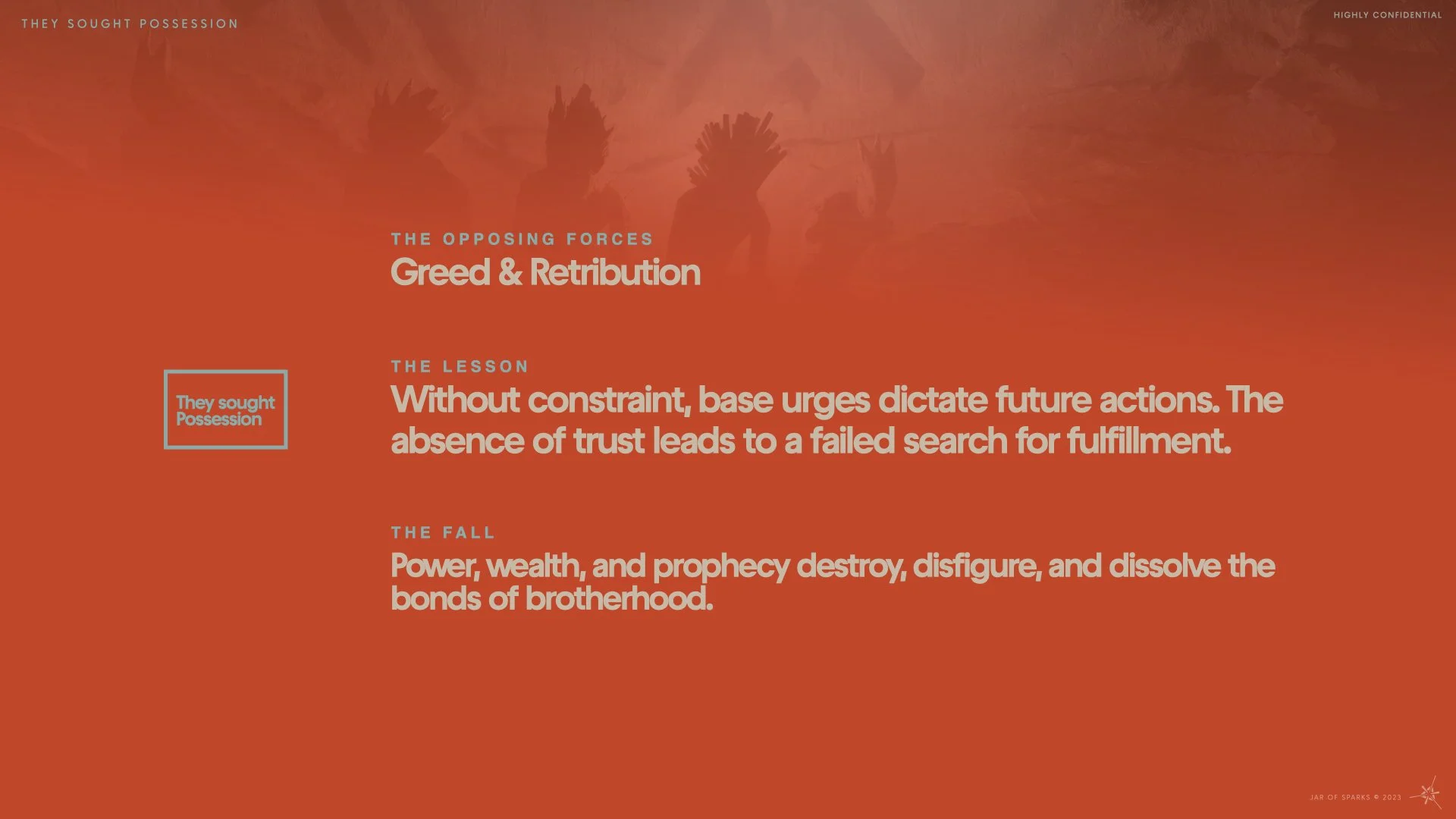

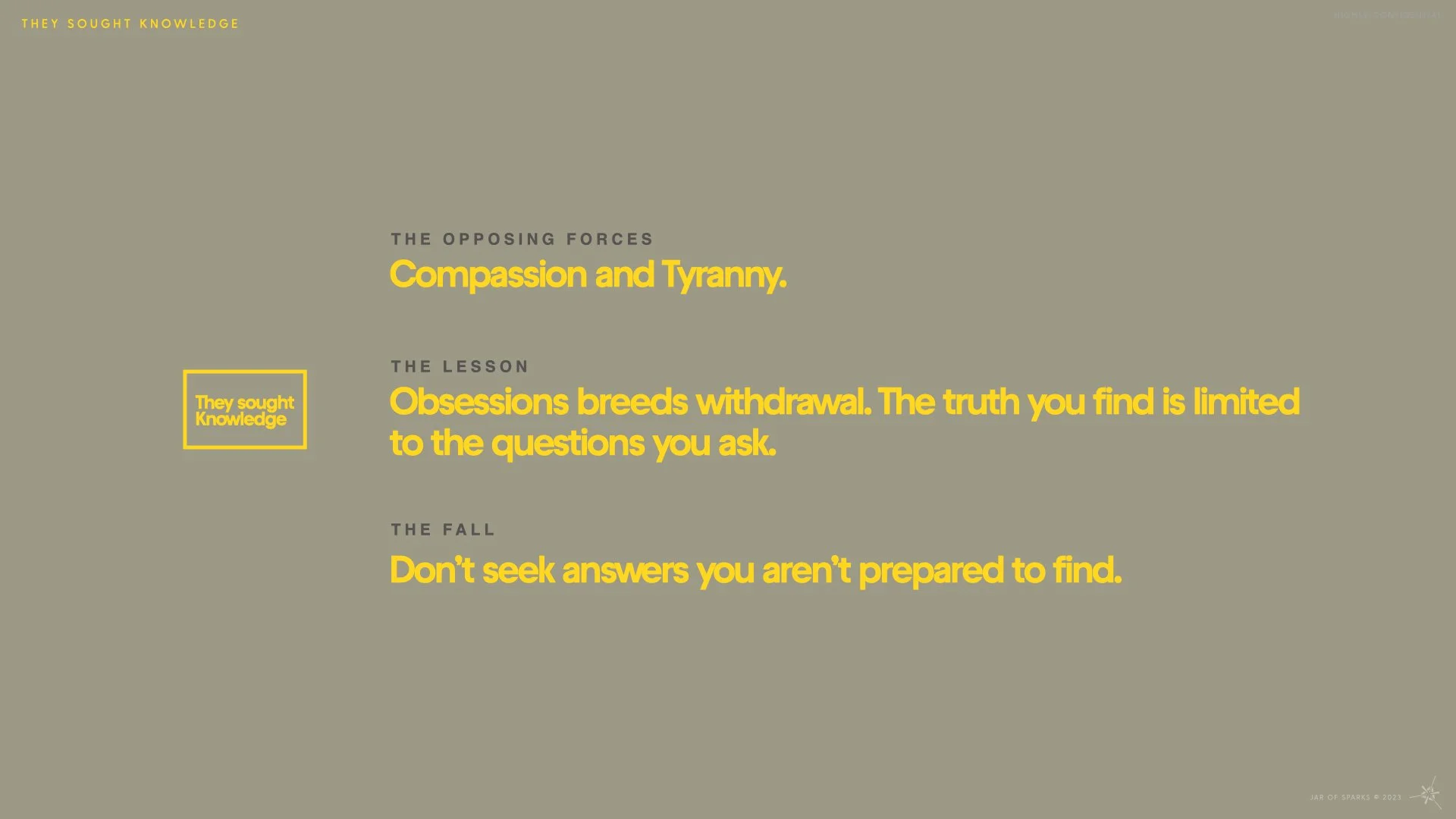

This video is a backstory that was created to try and imagine civilizations that could live in other dimensions. We used aspects of this but not anything explicitly.

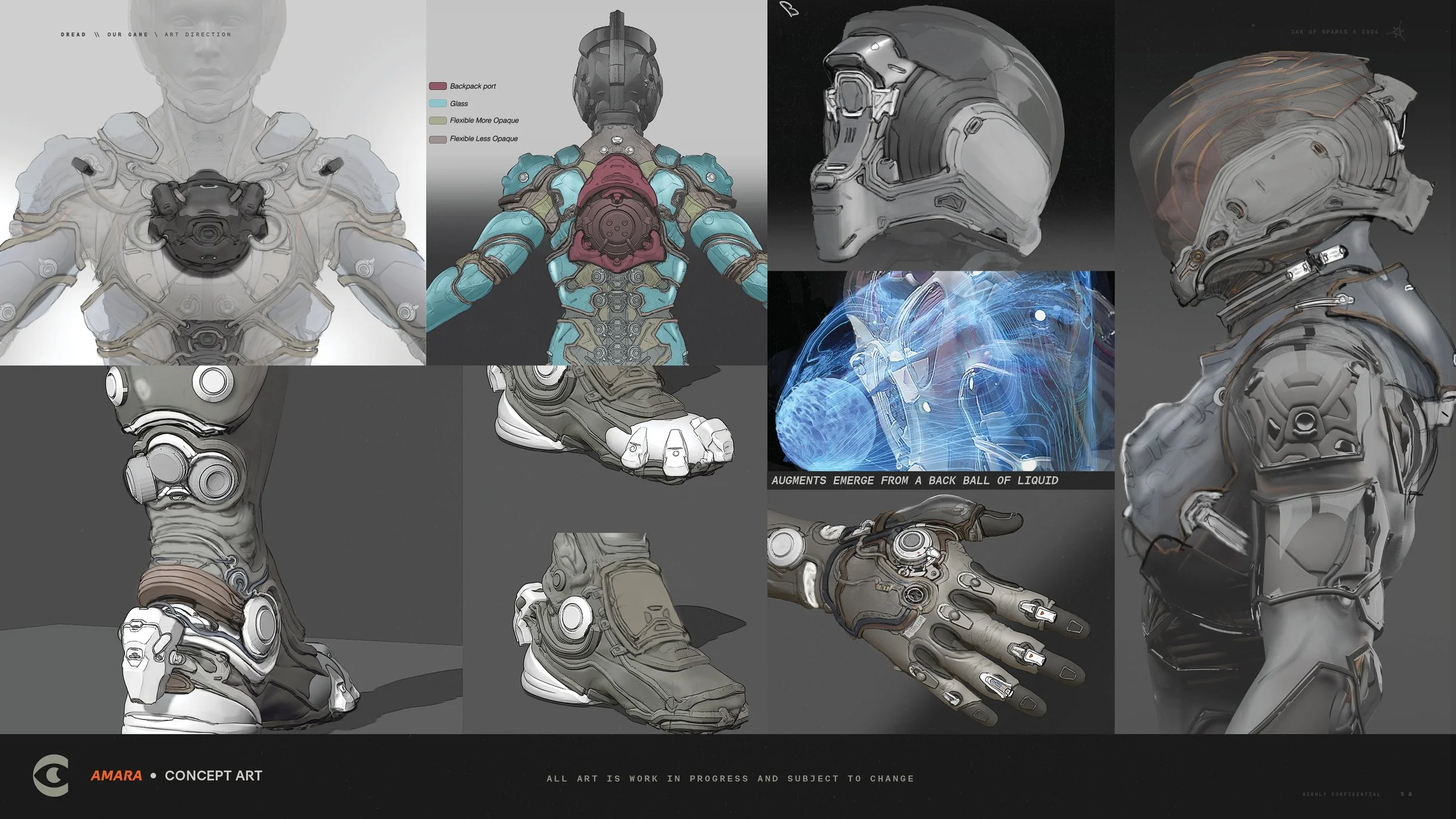

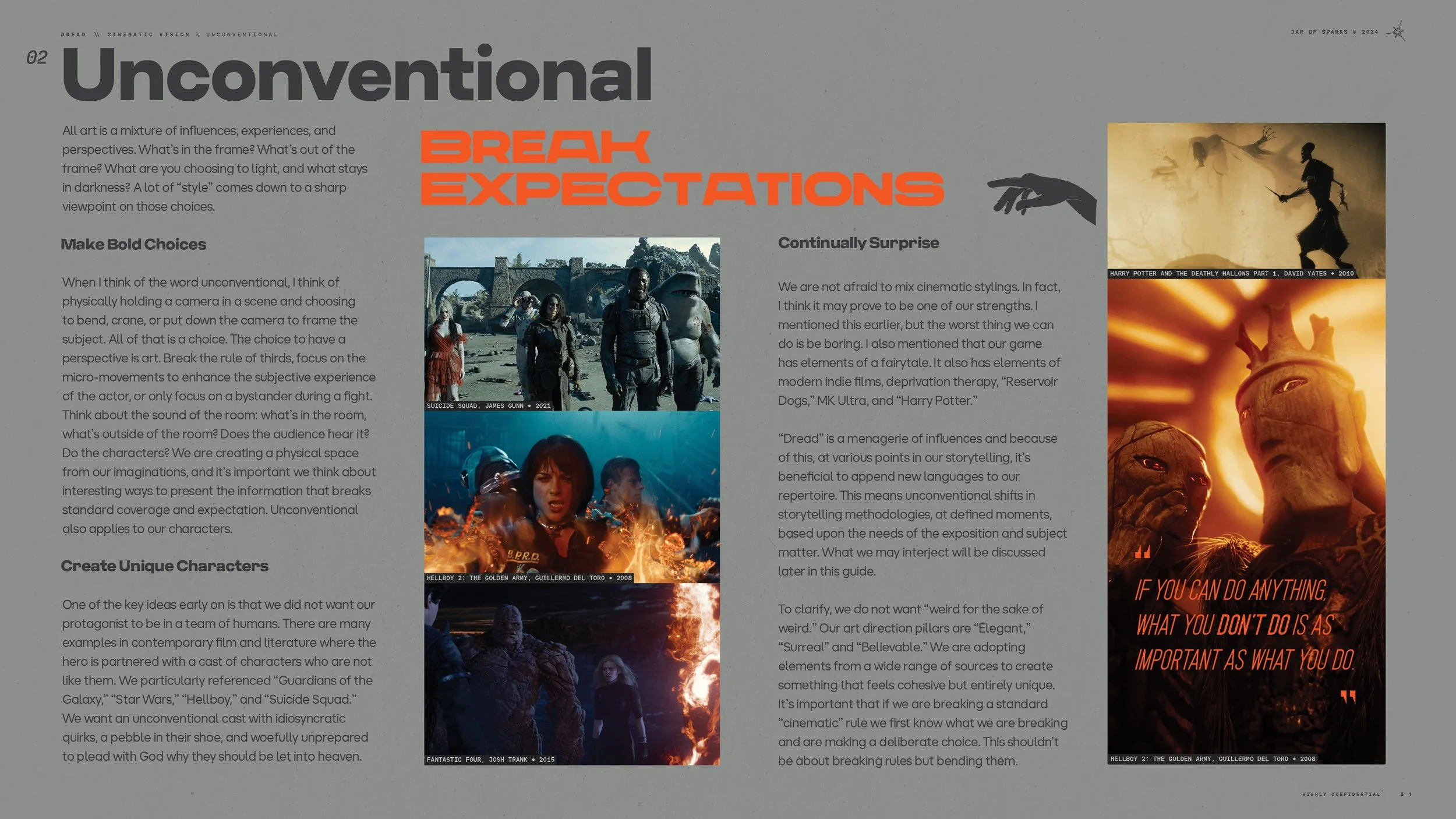

Augments: Evolution Through Conflict

Amara was not a superhero but a survivor. Her abilities came from Augments, technological and organic enhancements extracted from defeated foes. These Augments were not static upgrades; they reflected the creatures Amara encountered, allowing her to adapt to the alien environments in unpredictable ways. This system blurred the line between predator and prey, forcing players to think tactically about how they engaged with enemies.

Gravelegs Enemy Augment

The augment system changed but this is a pretty clear example of how an enemy could grant the player their primary attack.

Gravelegs Enemy Update

This video was animated and created by Lead Animator Scott Marshall to show how the Gravelegs emerges from the sand and hides within the scrap of the environment.

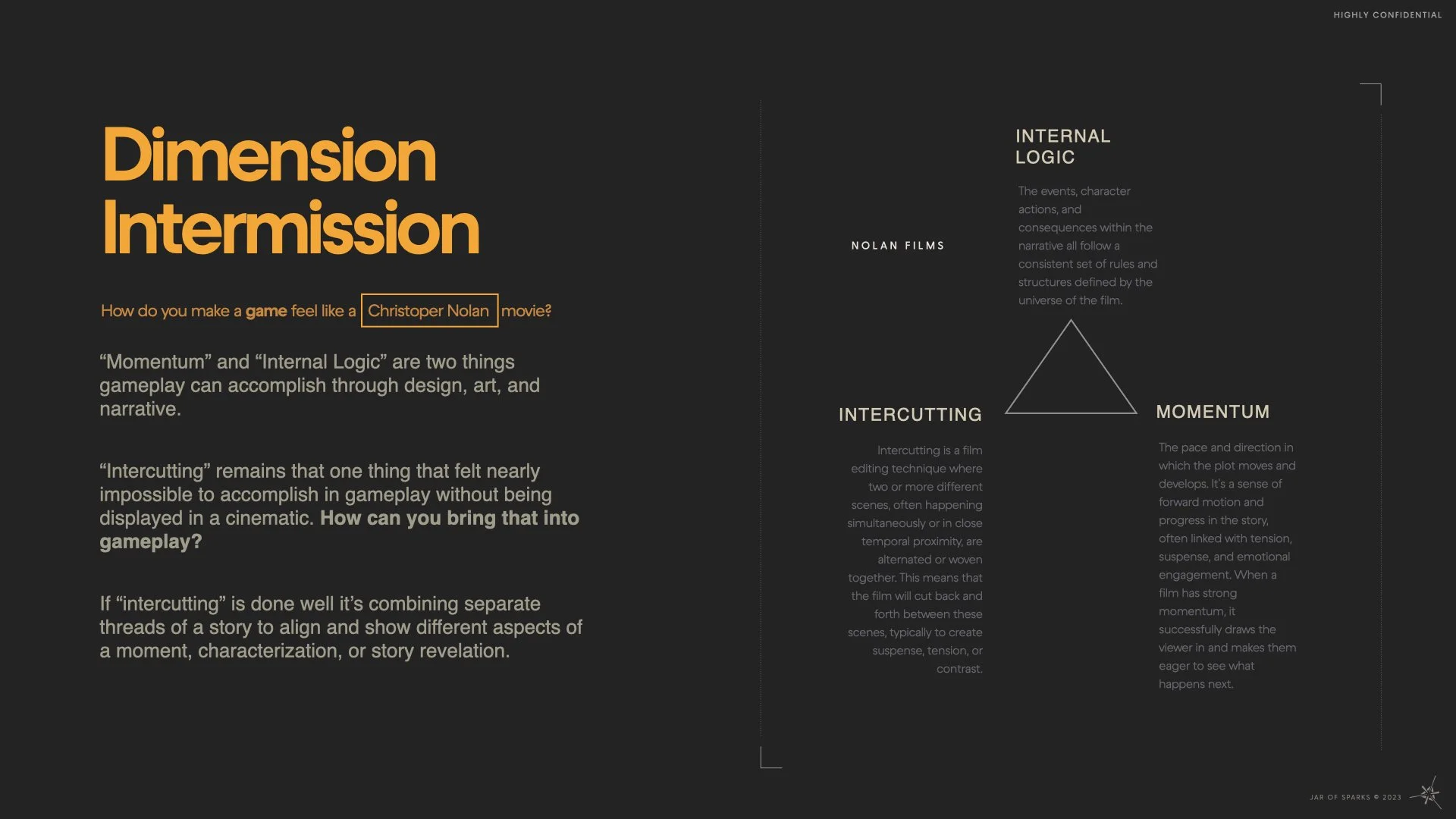

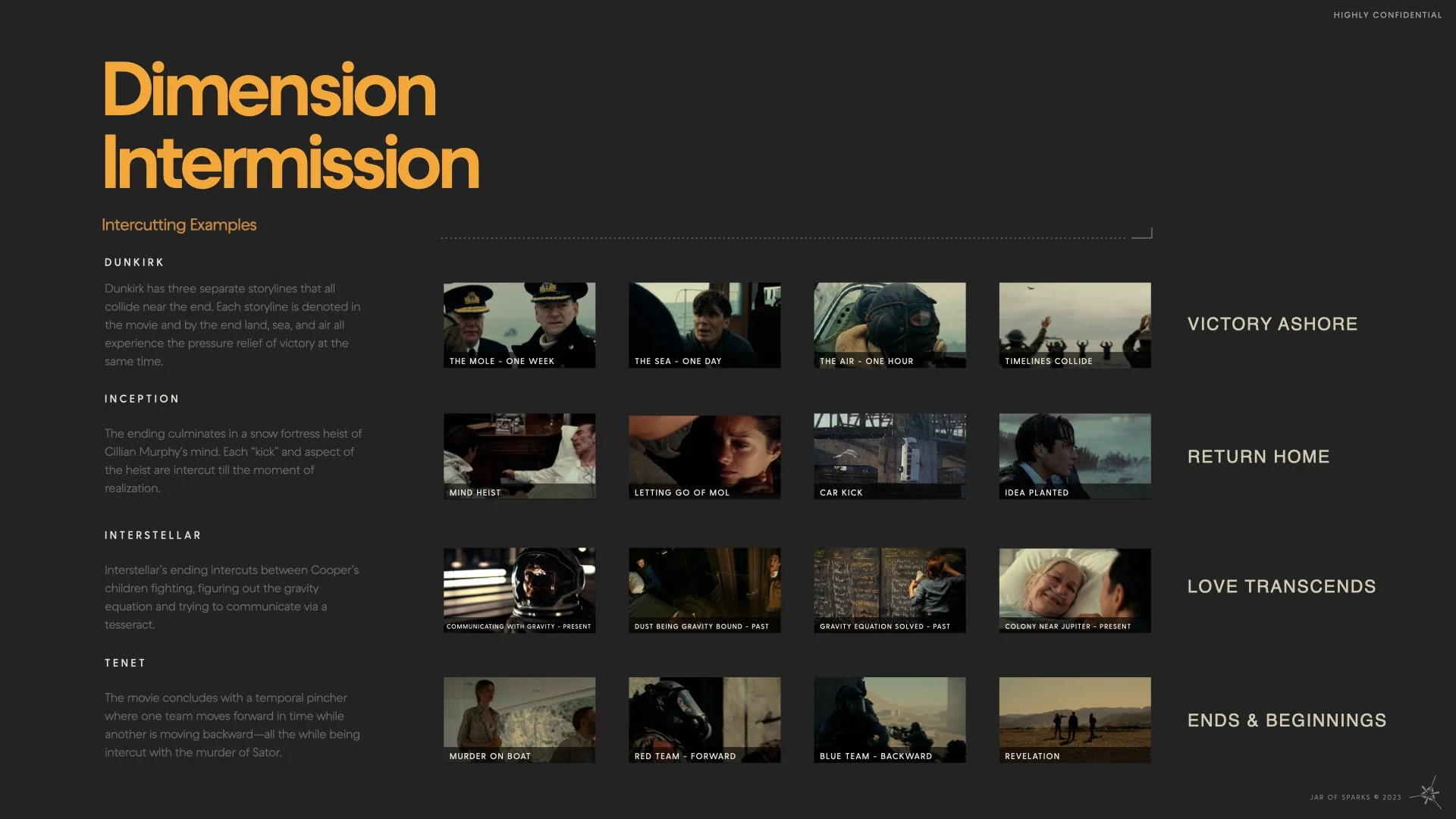

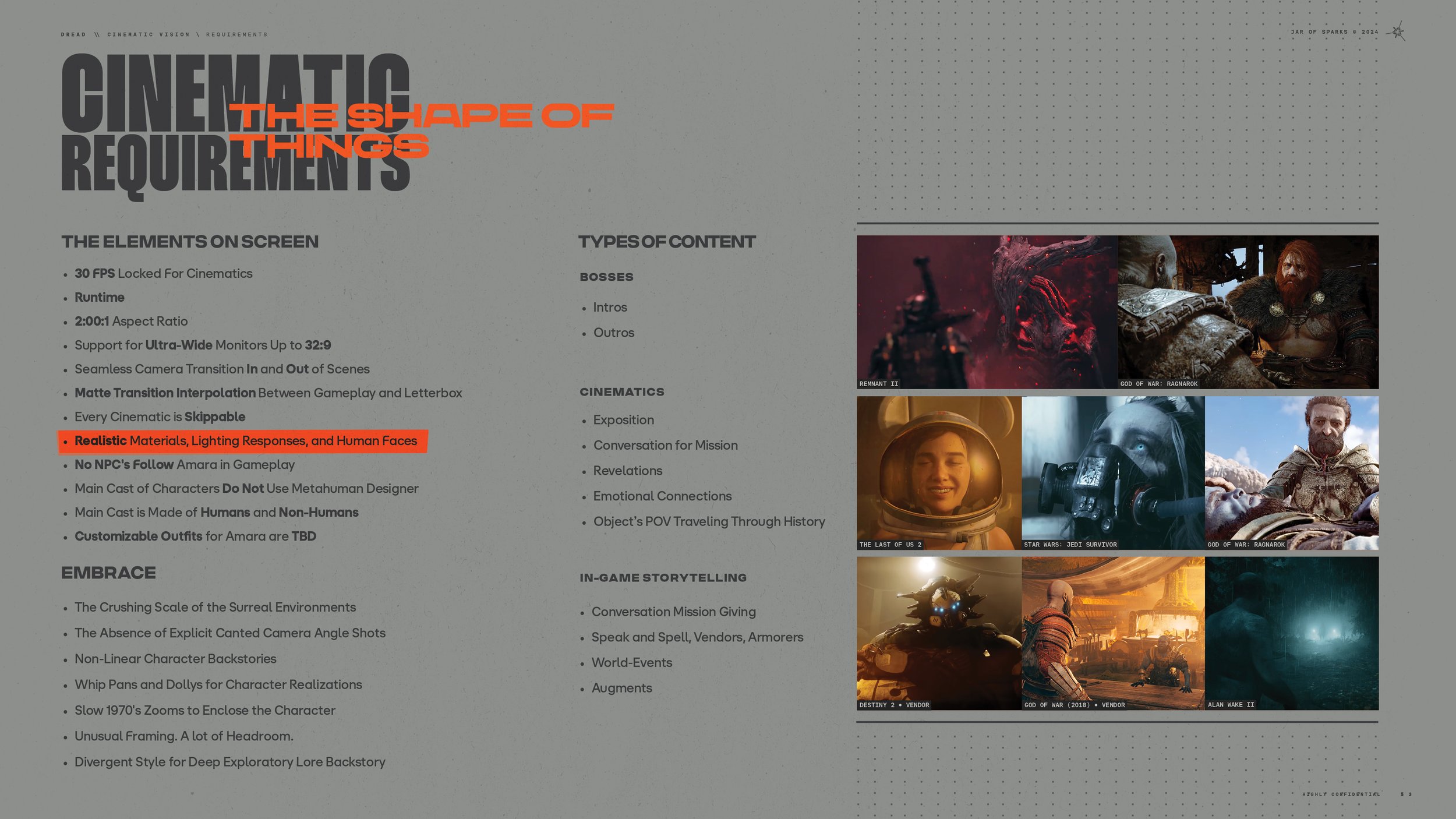

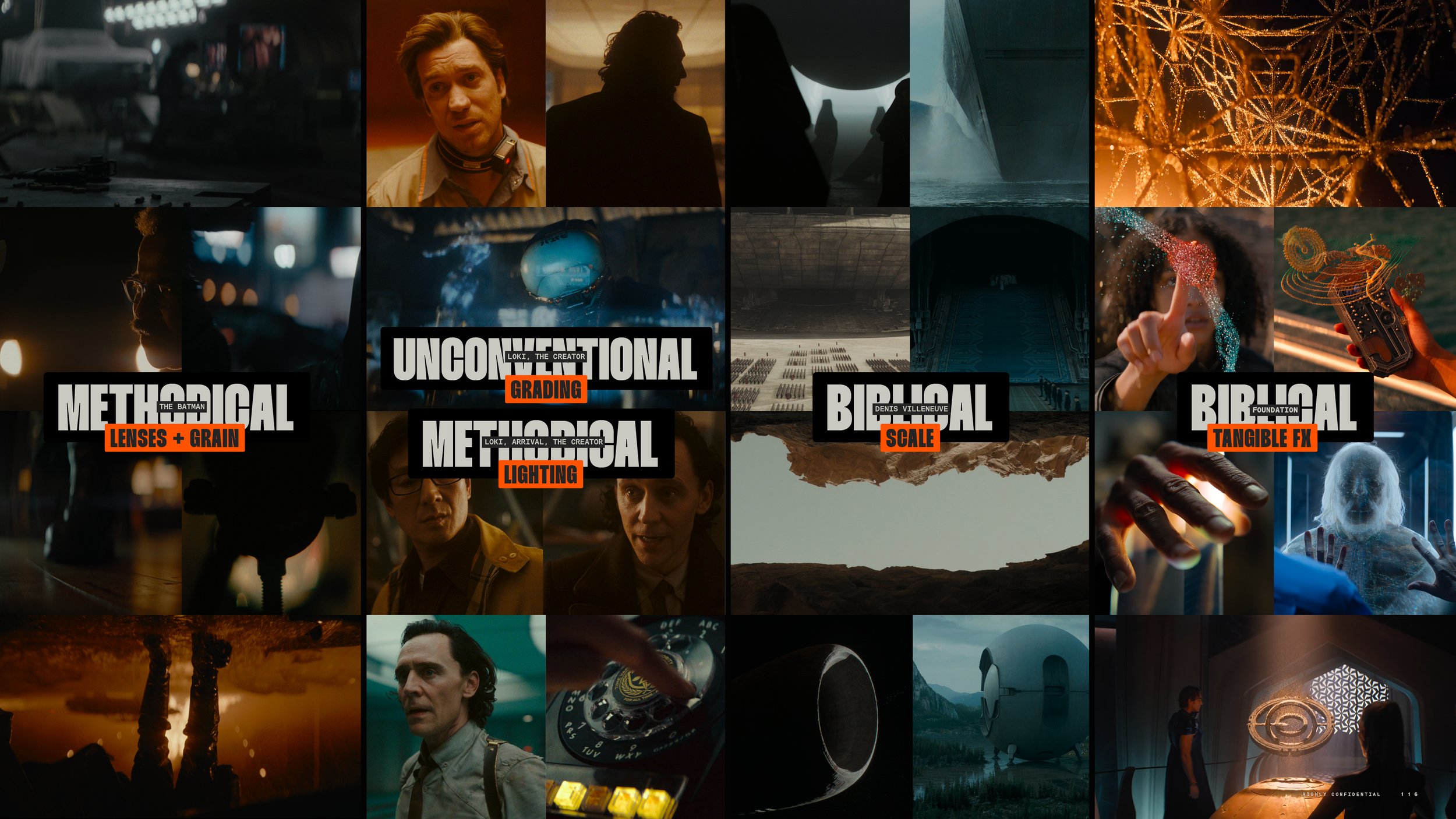

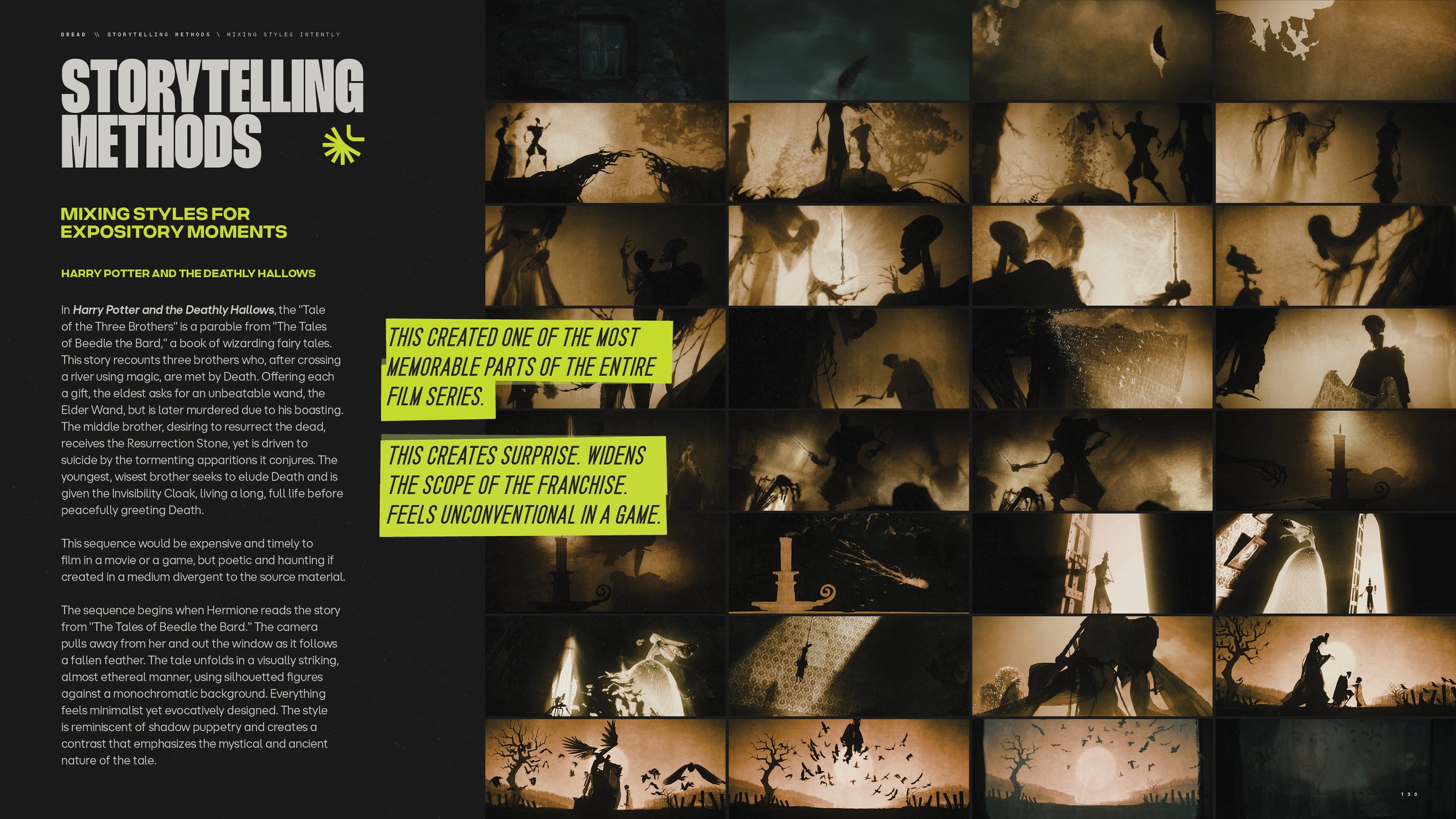

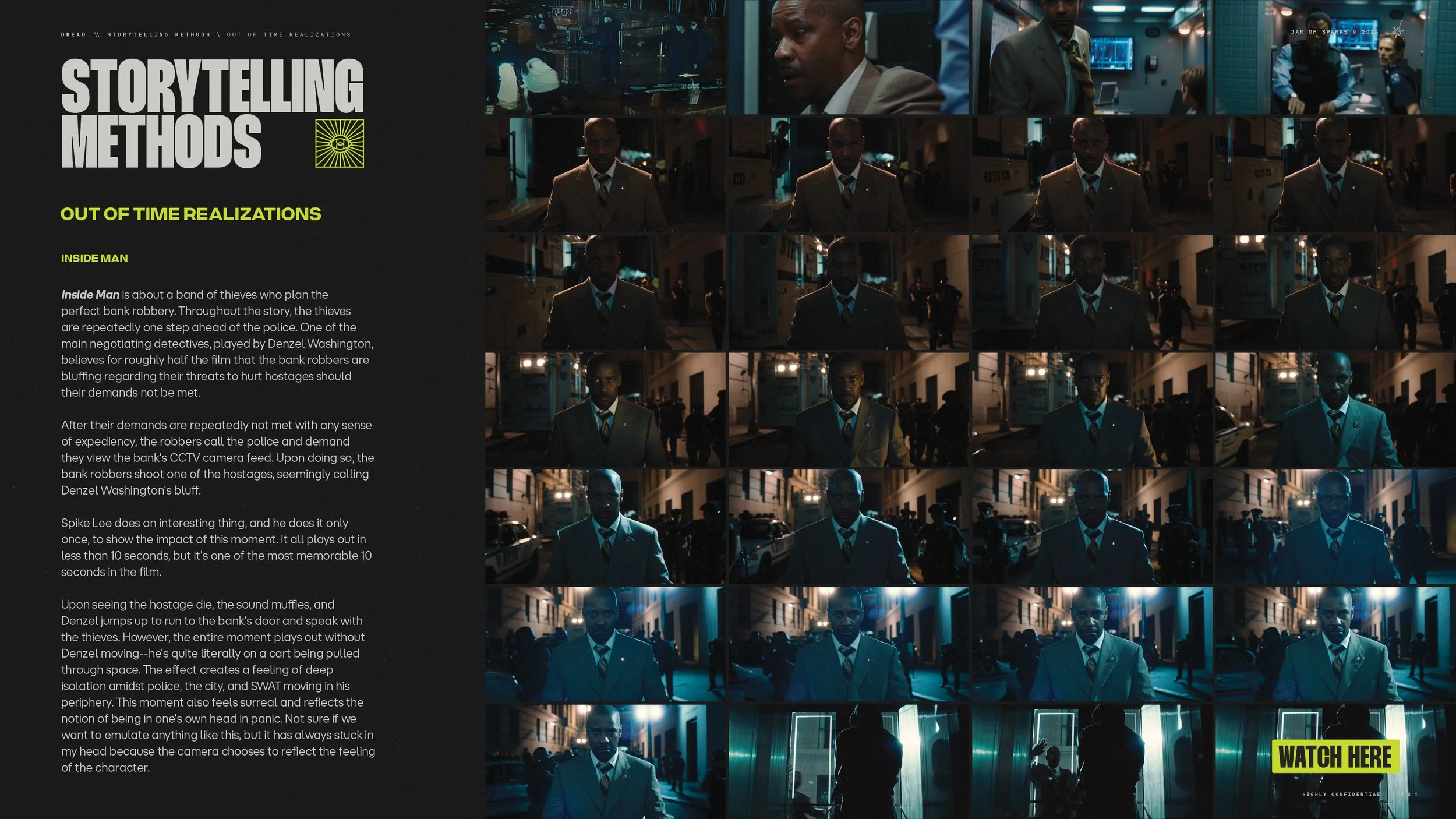

Dread Cinematic Guide

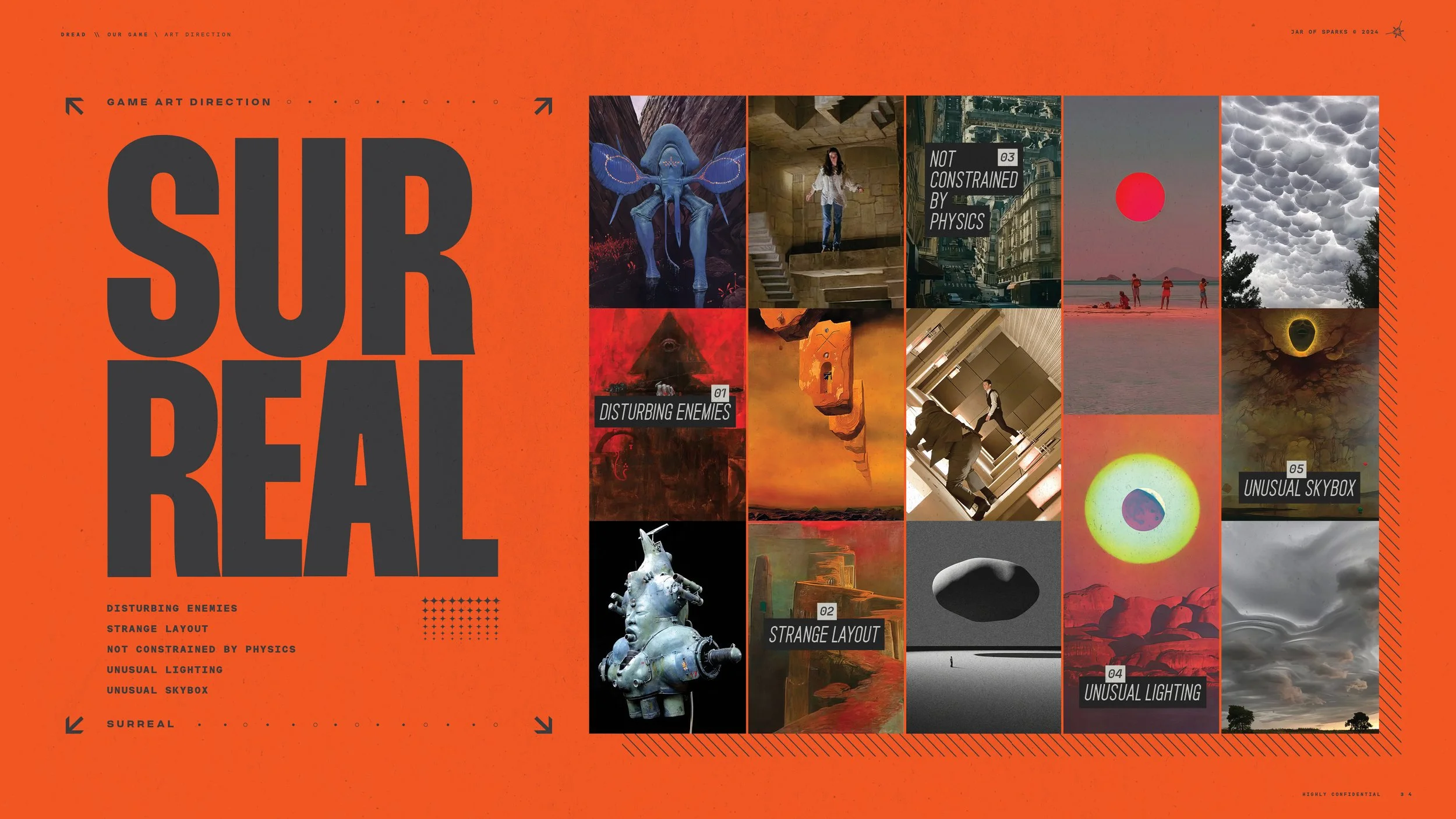

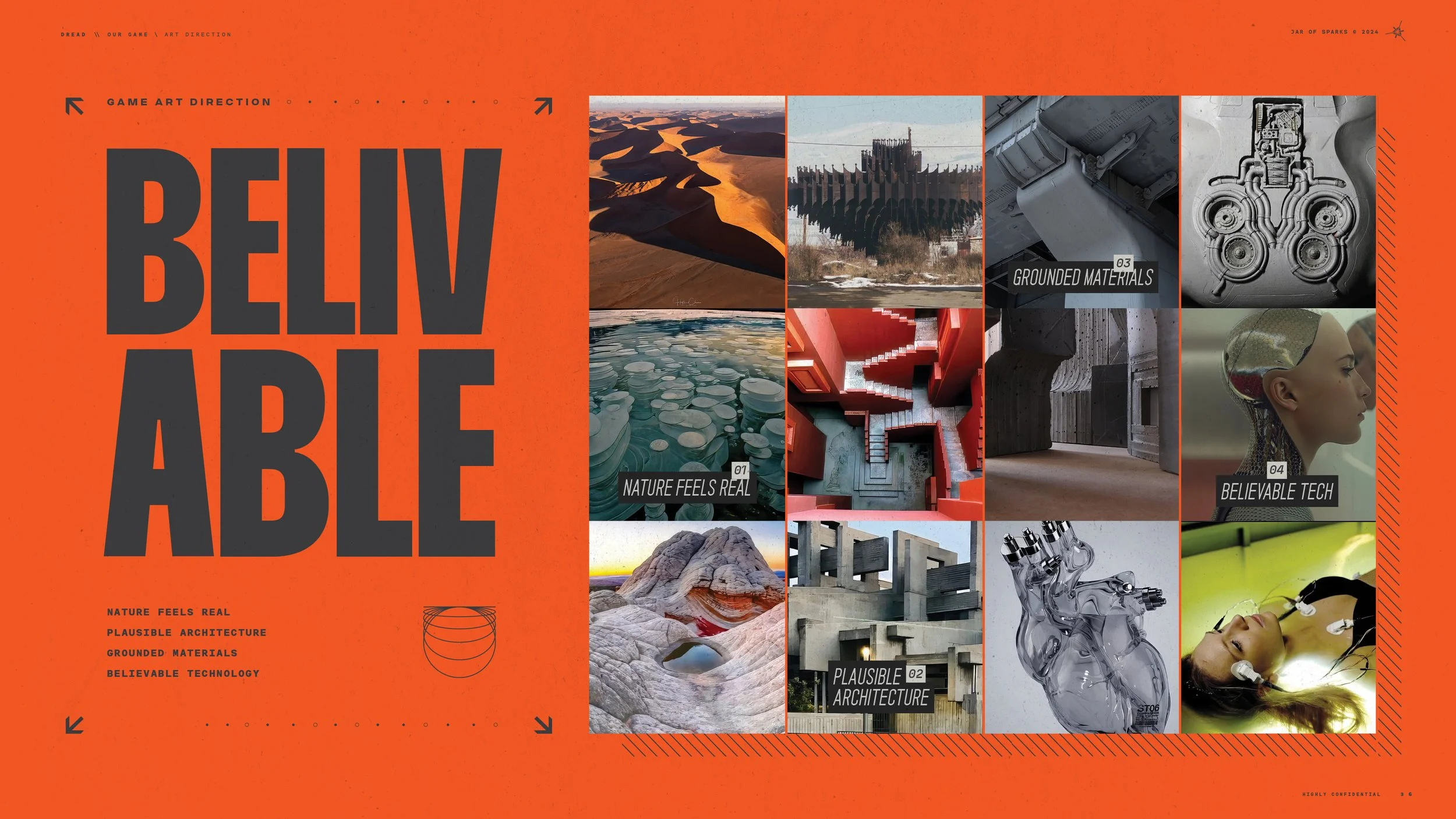

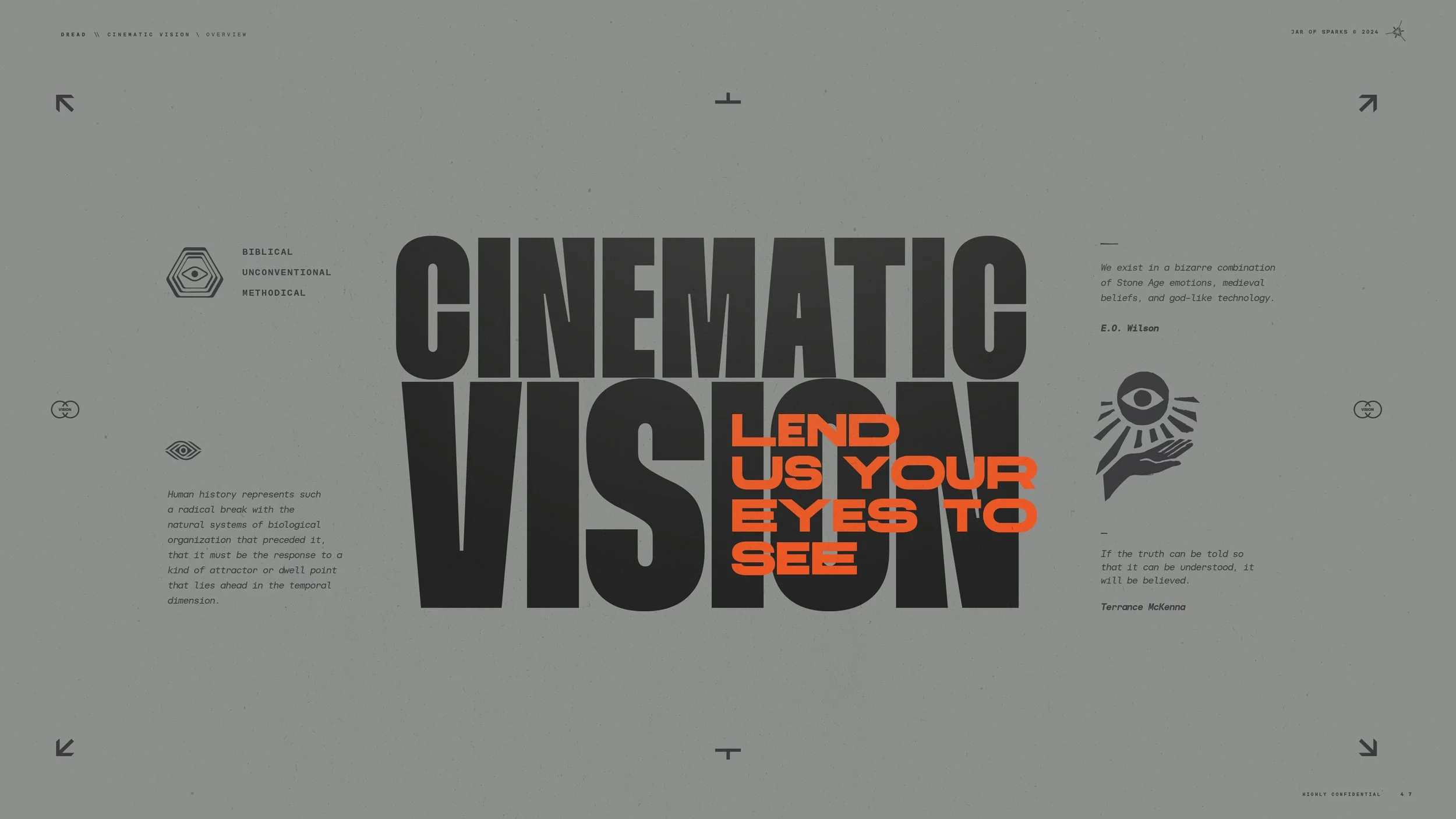

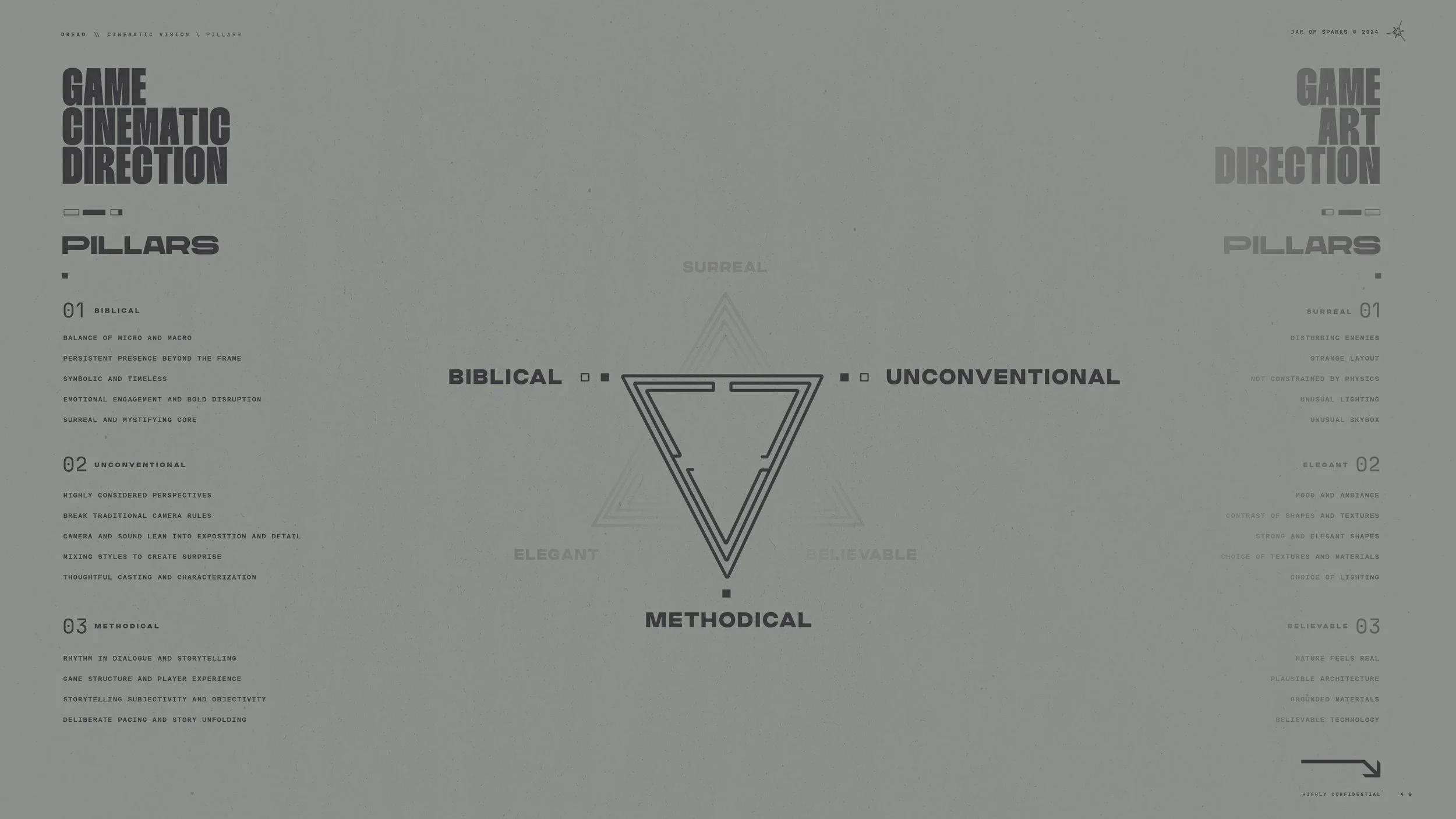

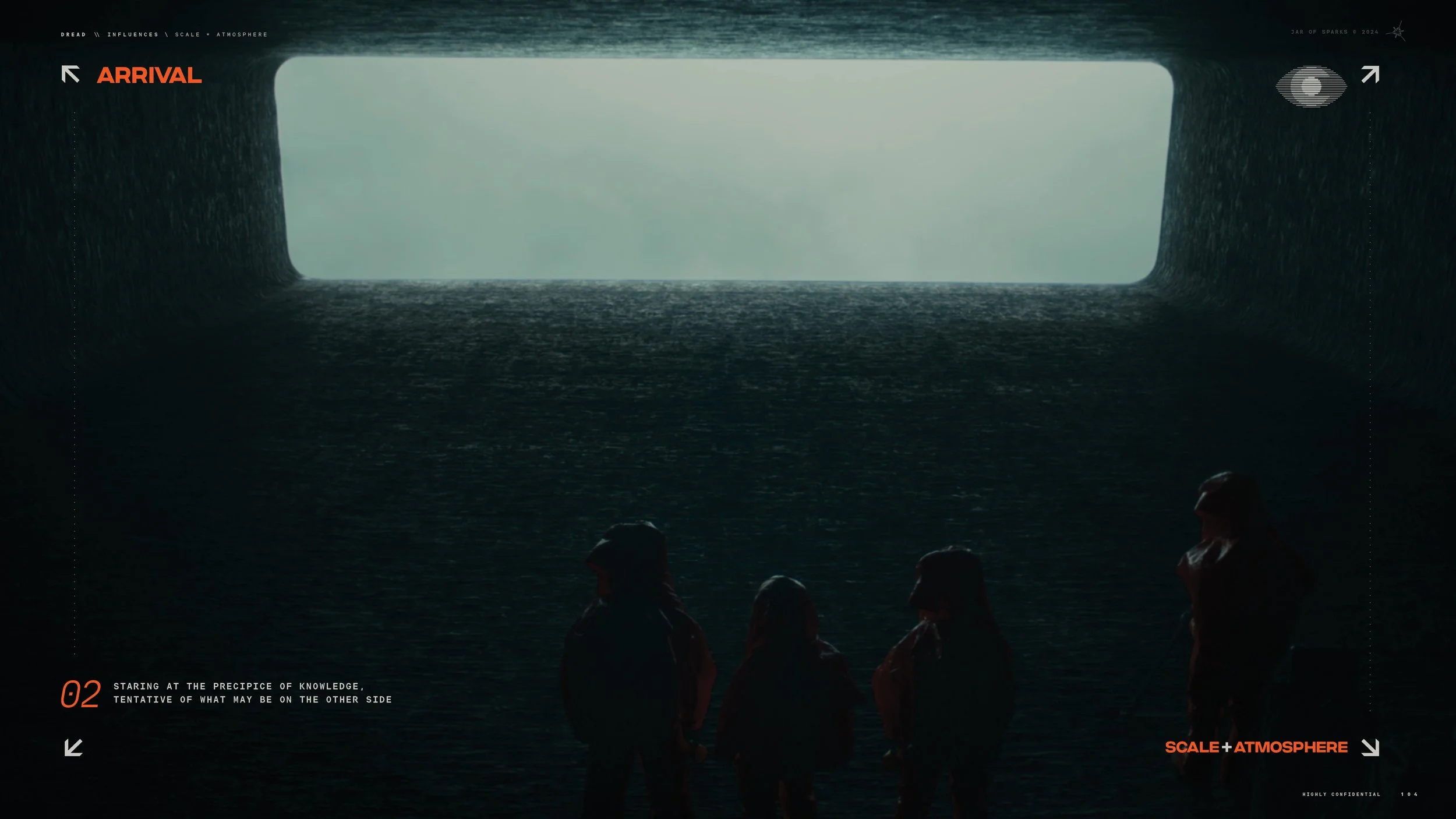

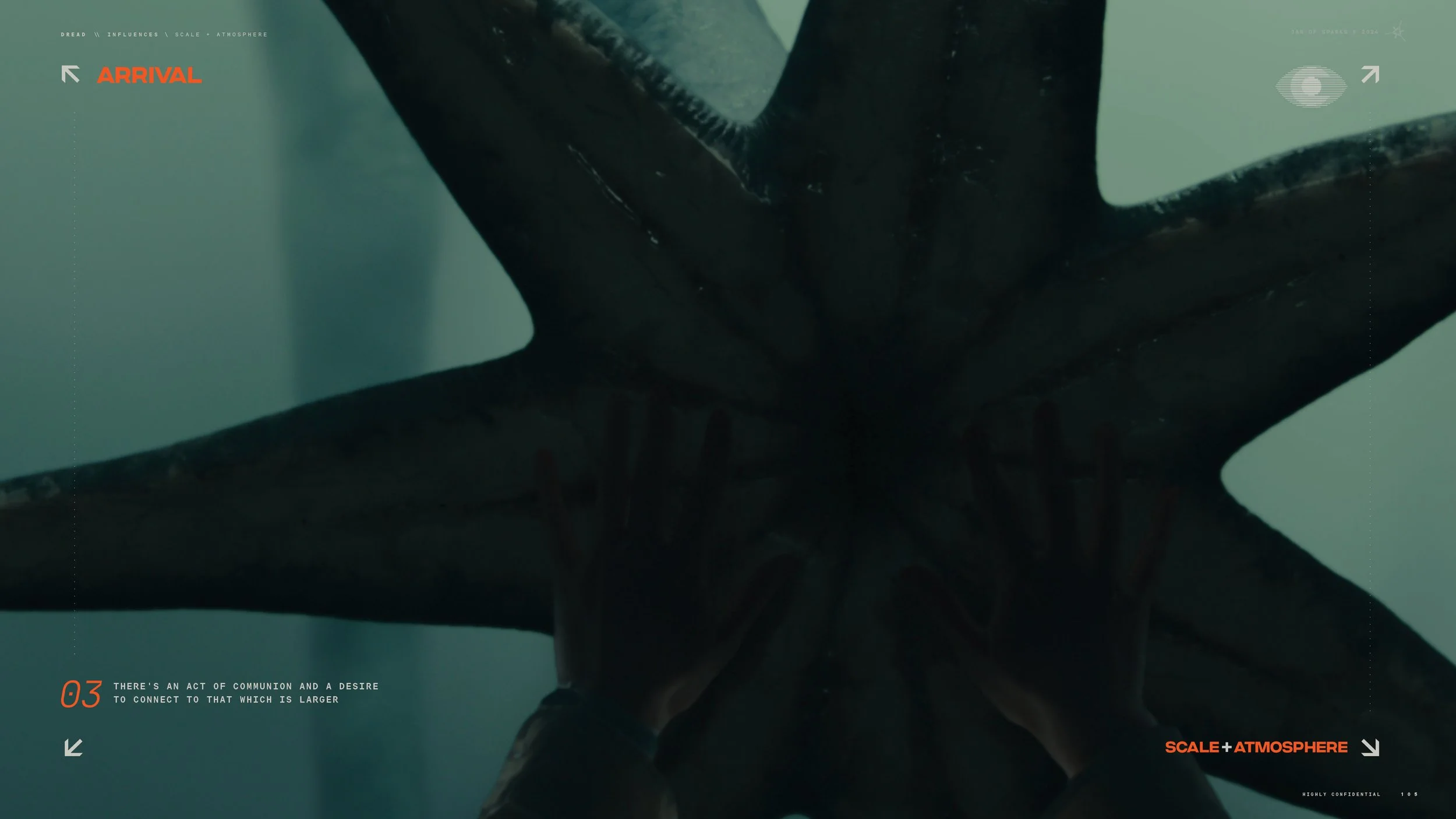

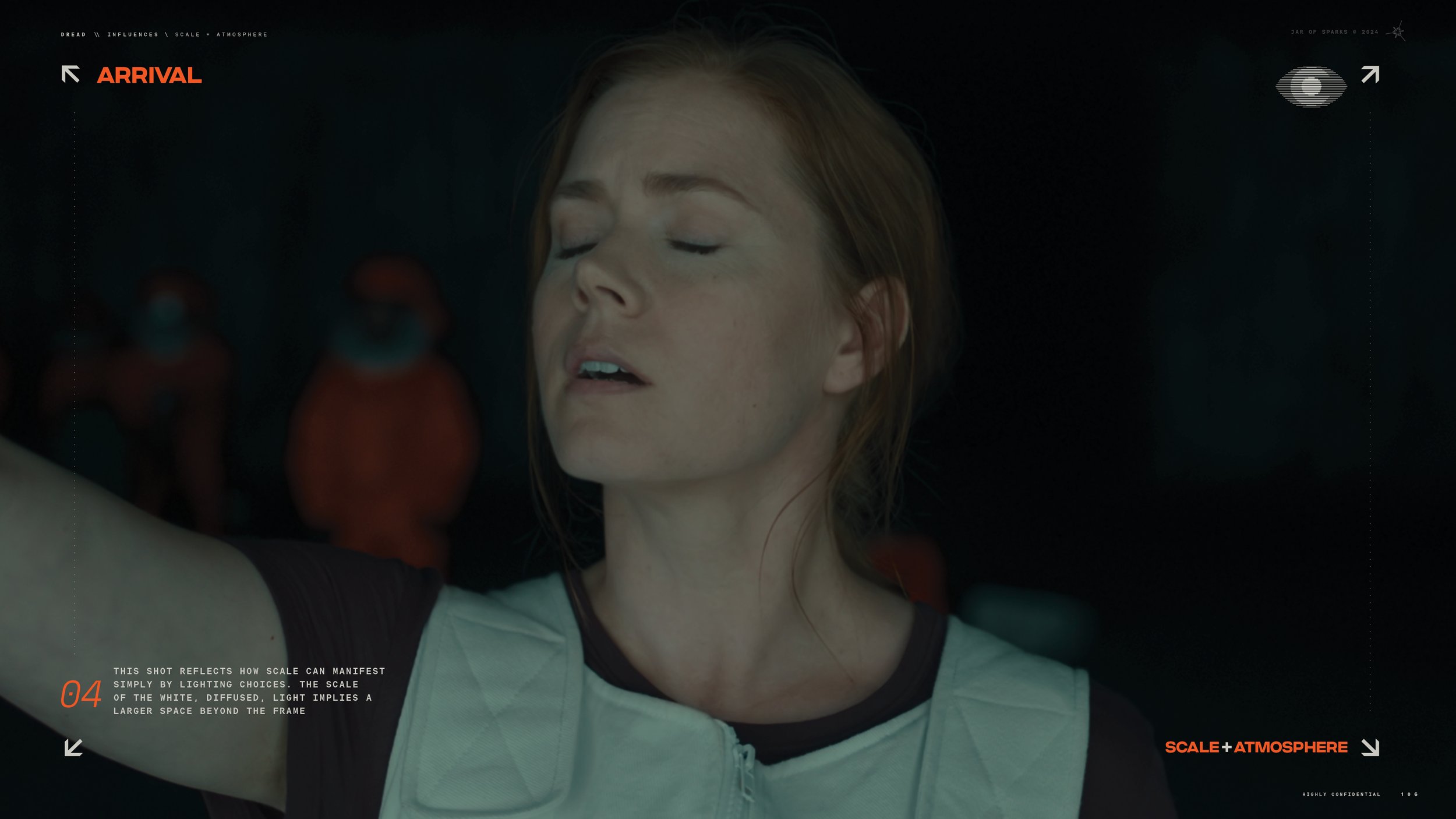

The Cinematic Guide for Dread aimed to capture a distinct and memorable visual and narrative identity that elevates the game’s storytelling beyond traditional cinematic experiences. The guide’s focus was on immersive, symbolic, and emotionally evocative storytelling that supports the game’s themes of cosmic horror, mystery, and exploration.

Cinematic Identity

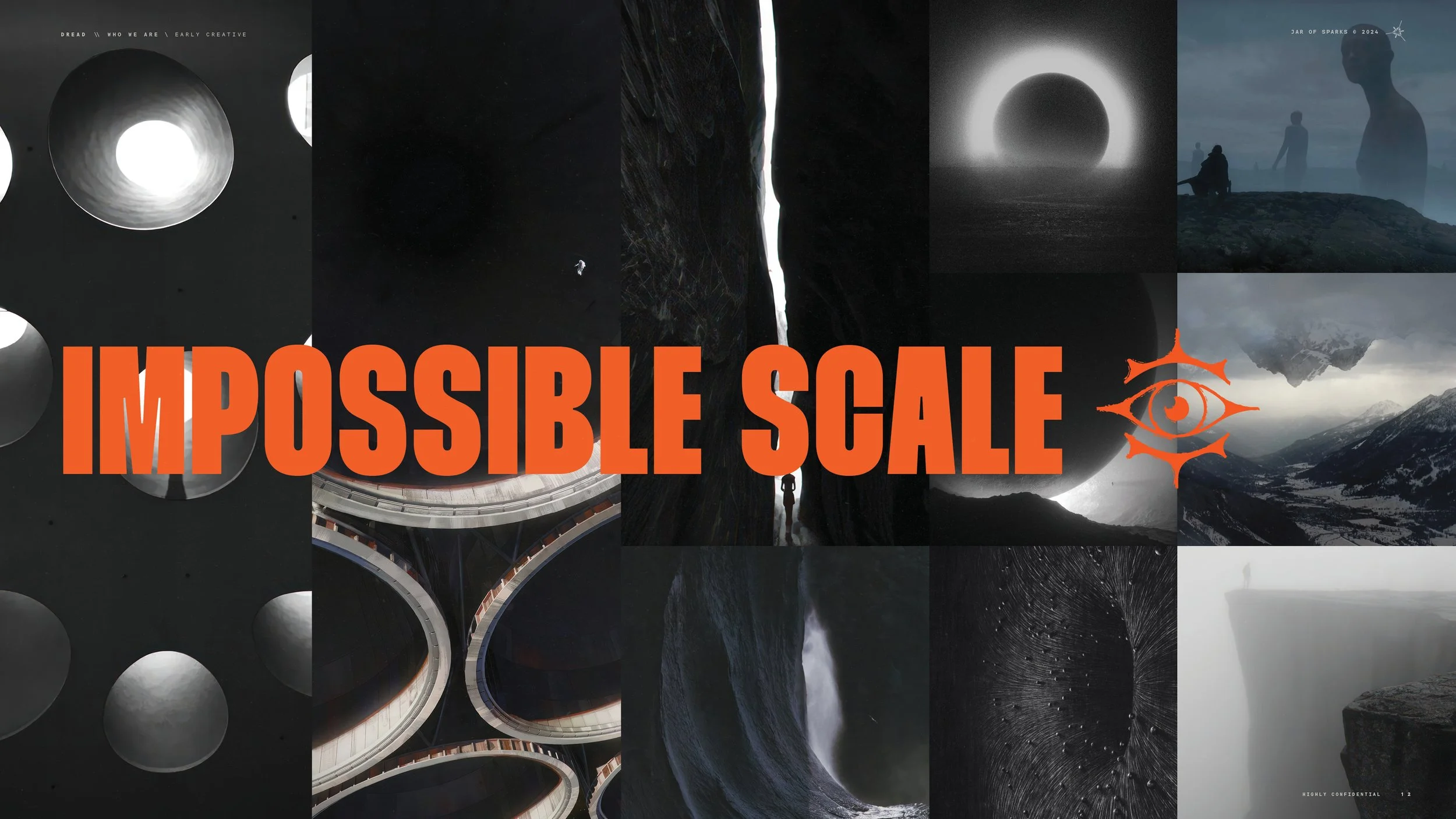

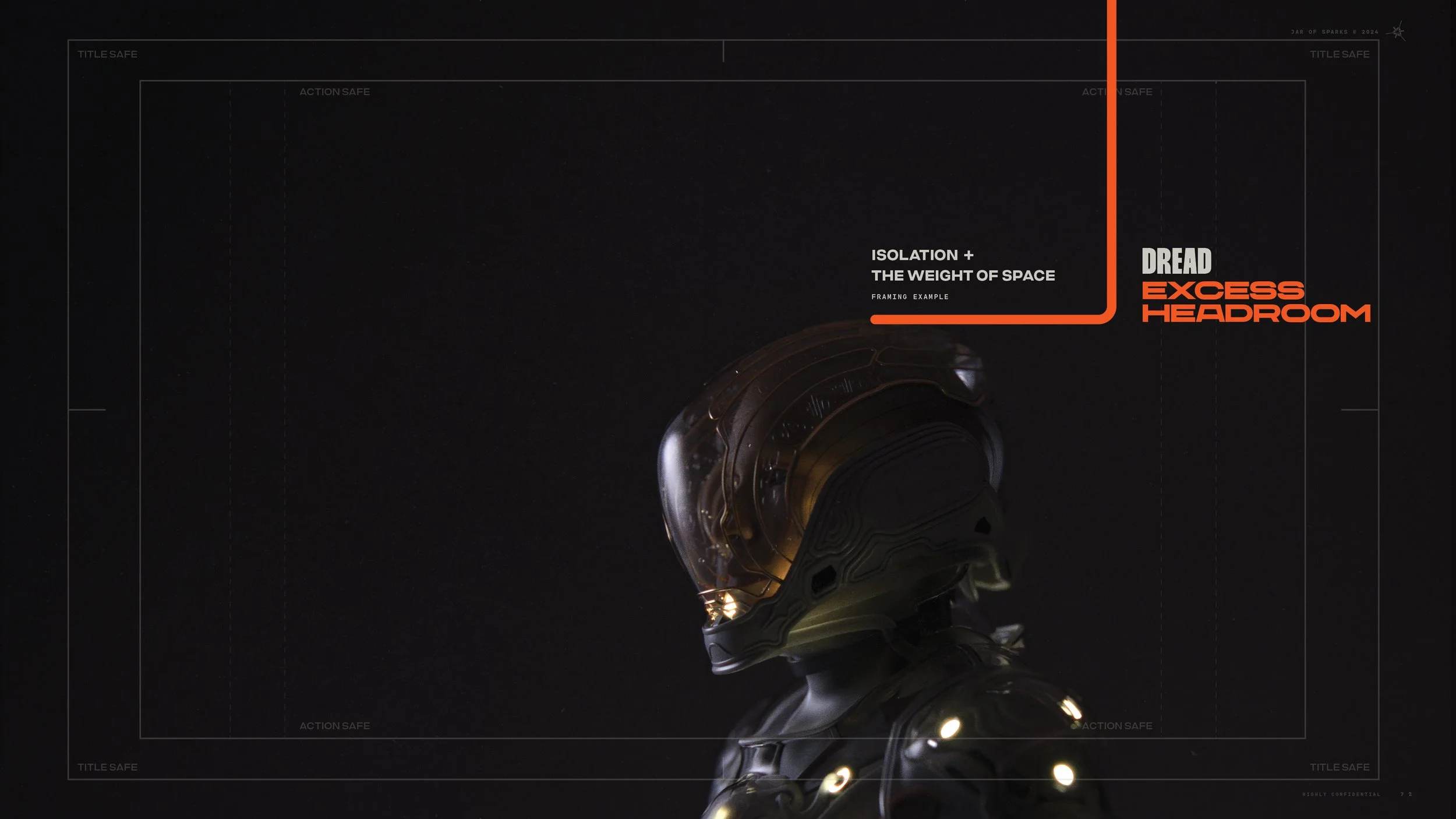

The guide sought to establish a unique, recognizable visual language for Dread. This meant moving away from conventional AAA cinematics and instead focusing on:

• Unconventional framing (placing characters in lower thirds, using negative space)

• Deliberate use of scale (to create awe, insignificance, or power)

• Surreal transitions (moving seamlessly between game and cinematics)

• A sense of discomfort and intrigue through visual composition

Thematic and Symbolic Storytelling

A key goal was to ensure that every cinematic moment had layers of meaning. The cinematics in Dread are designed to be:

• Biblical: Grand, mythological scale that evokes ancient power struggles.

• Unconventional: Using framing, movement, and perspective to subvert expectations.

• Methodical: Carefully paced storytelling that rewards player curiosity and patience .

This approach meant that no shot was just about delivering dialogue—it also had to convey character psychology, foreshadow events, or reinforce the game’s themes.

Seven Cinematic Influences

1. Christopher Nolan: High Concept Sensibility

Grounds the audience in a plausible reality

Lean on non-linearity to build character over time

"Character" happens based upon conflict and solution

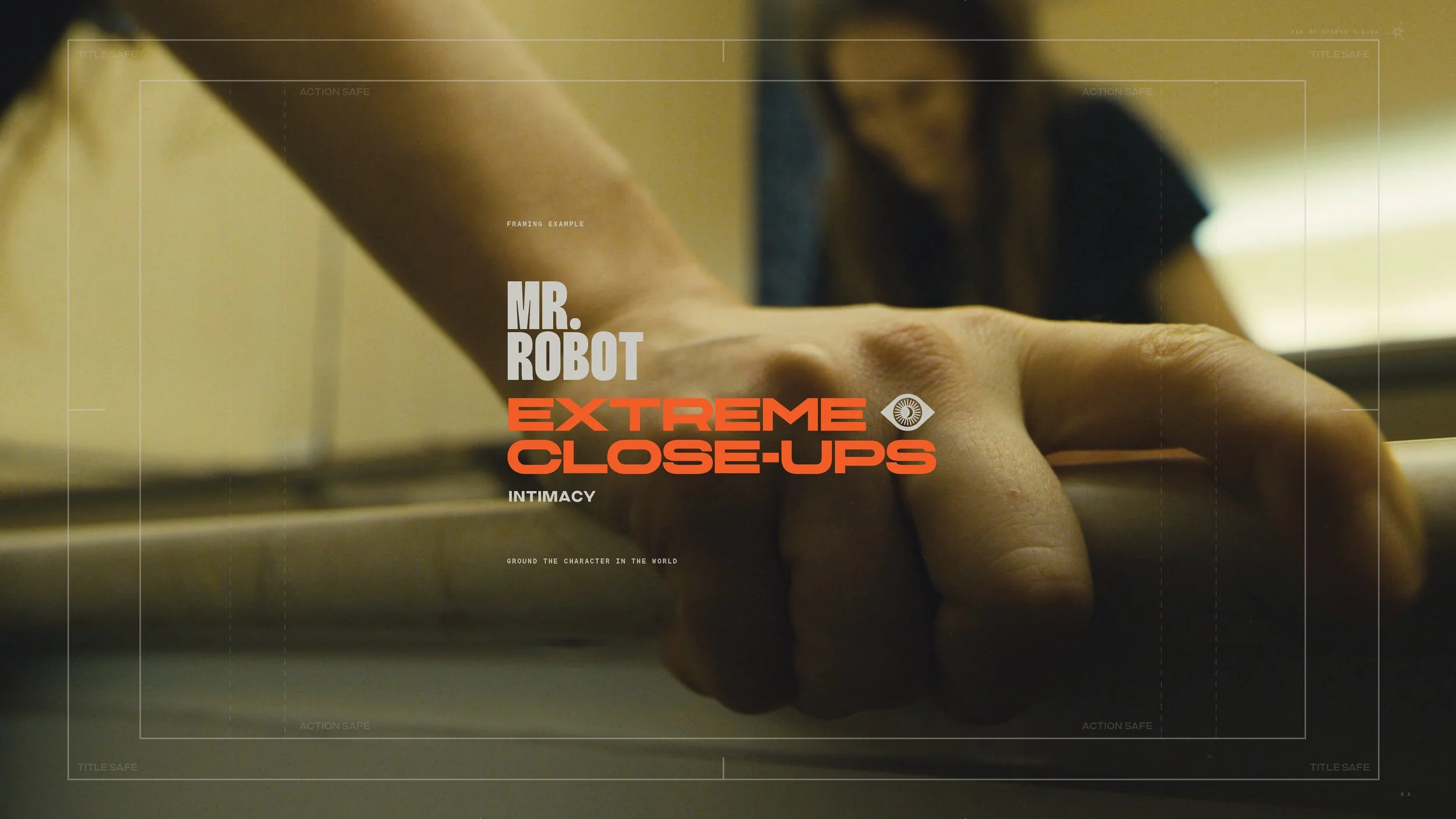

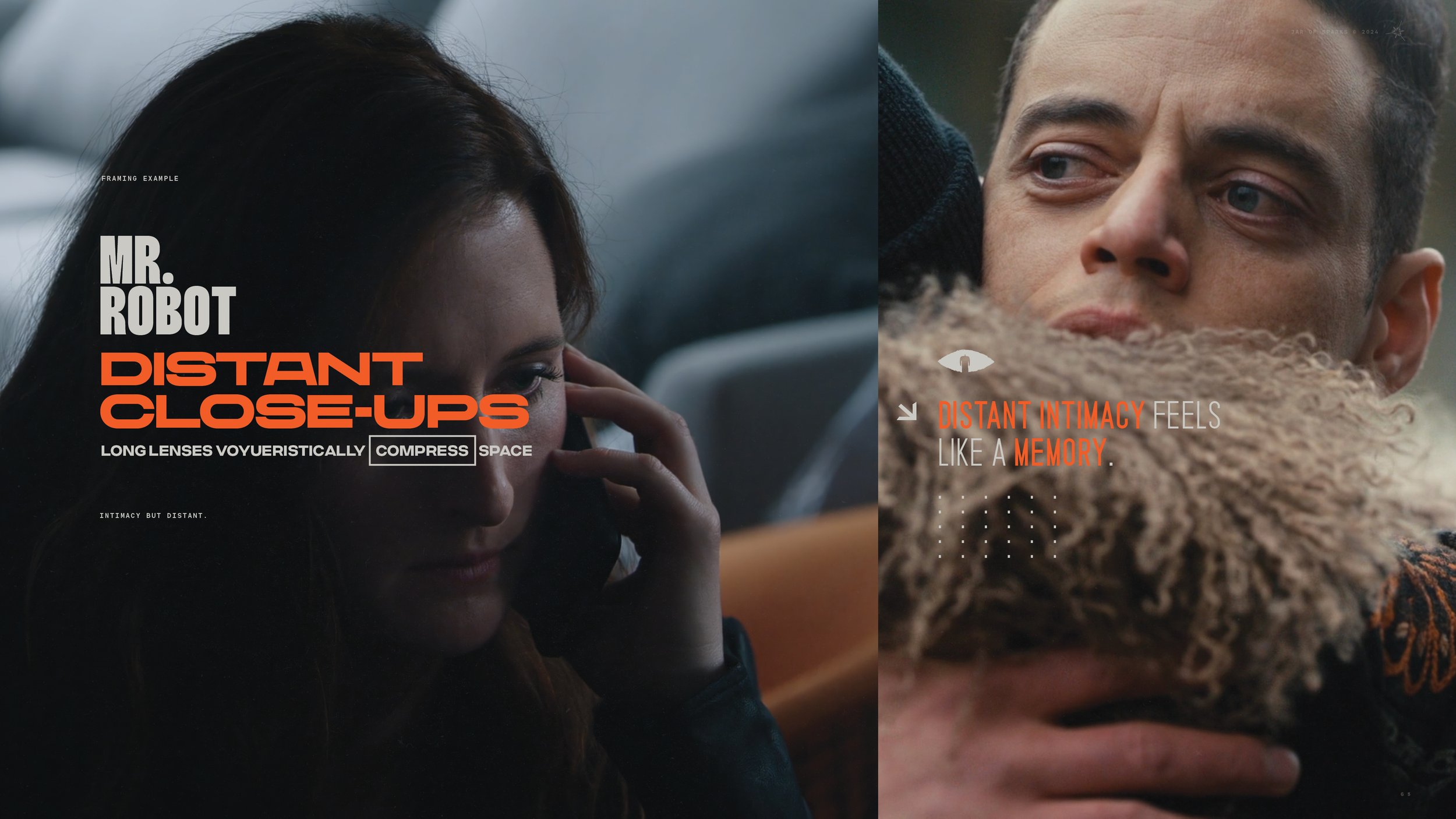

2. Mr. Robot: Framing

Rule-breaking composition

Space above amplifies the feeling of vulnerability, isolation, and pressure

Direct address draws the audience into the world

Distant Closeups: Long lenses voyueristically compress space

Tight and personal close-ups to ground the character

Out-of-focus foreground objects lends to paranoia & voyeurism

Layers of information in a static shot--action plays out in the blocking.

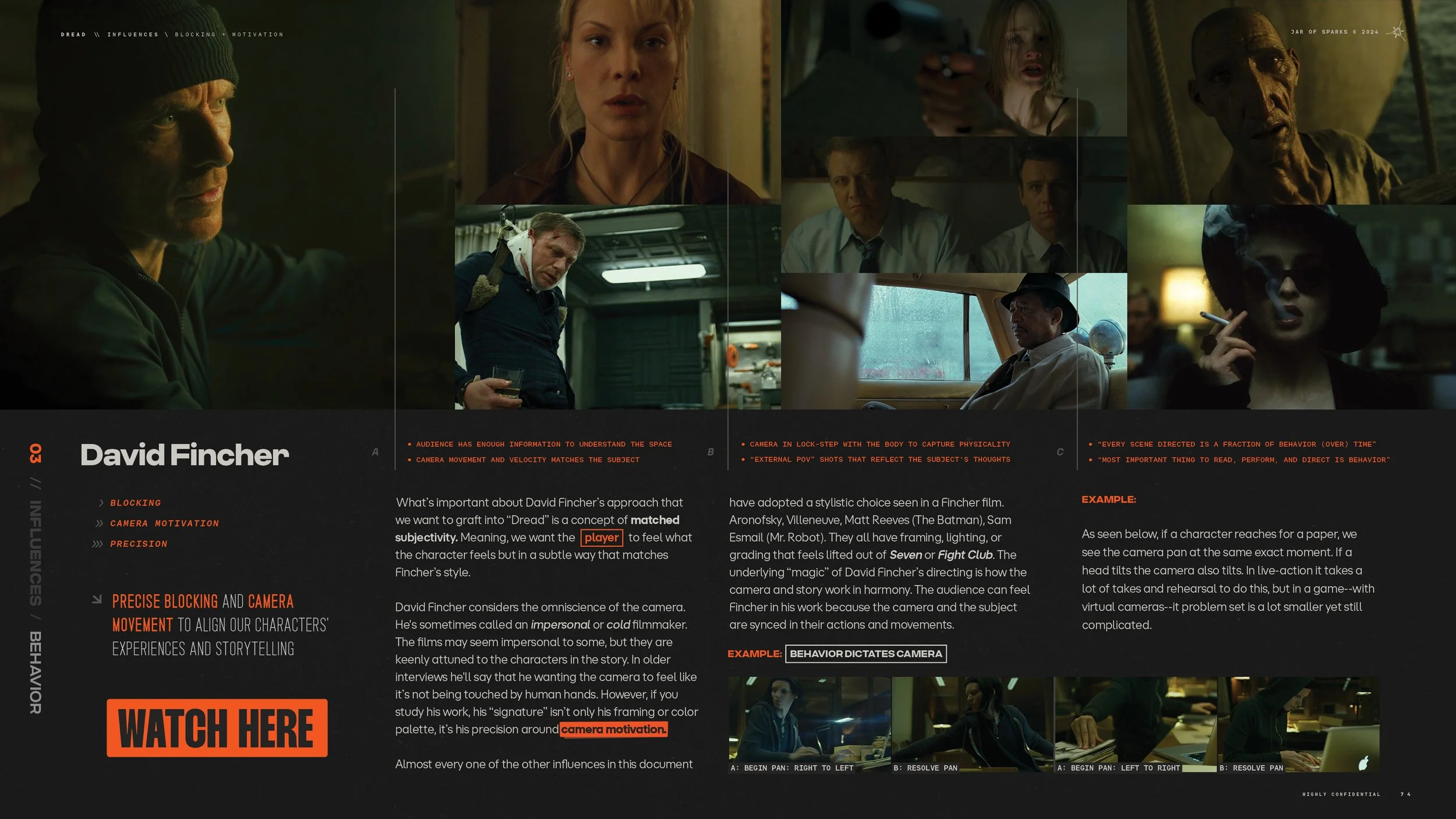

3. David Fincher: Blocking, Camera Motivation & Precision

Audience has enough information to understand the space

Camera movement and velocity matches the subject

Camera in lock-step with the body to capture physicality

“External POV” shots that reflect the subject's thoughts

“Every scene directed is a fraction of behavior (over) time”

Most important thing to read, perform, and Direct is behavior

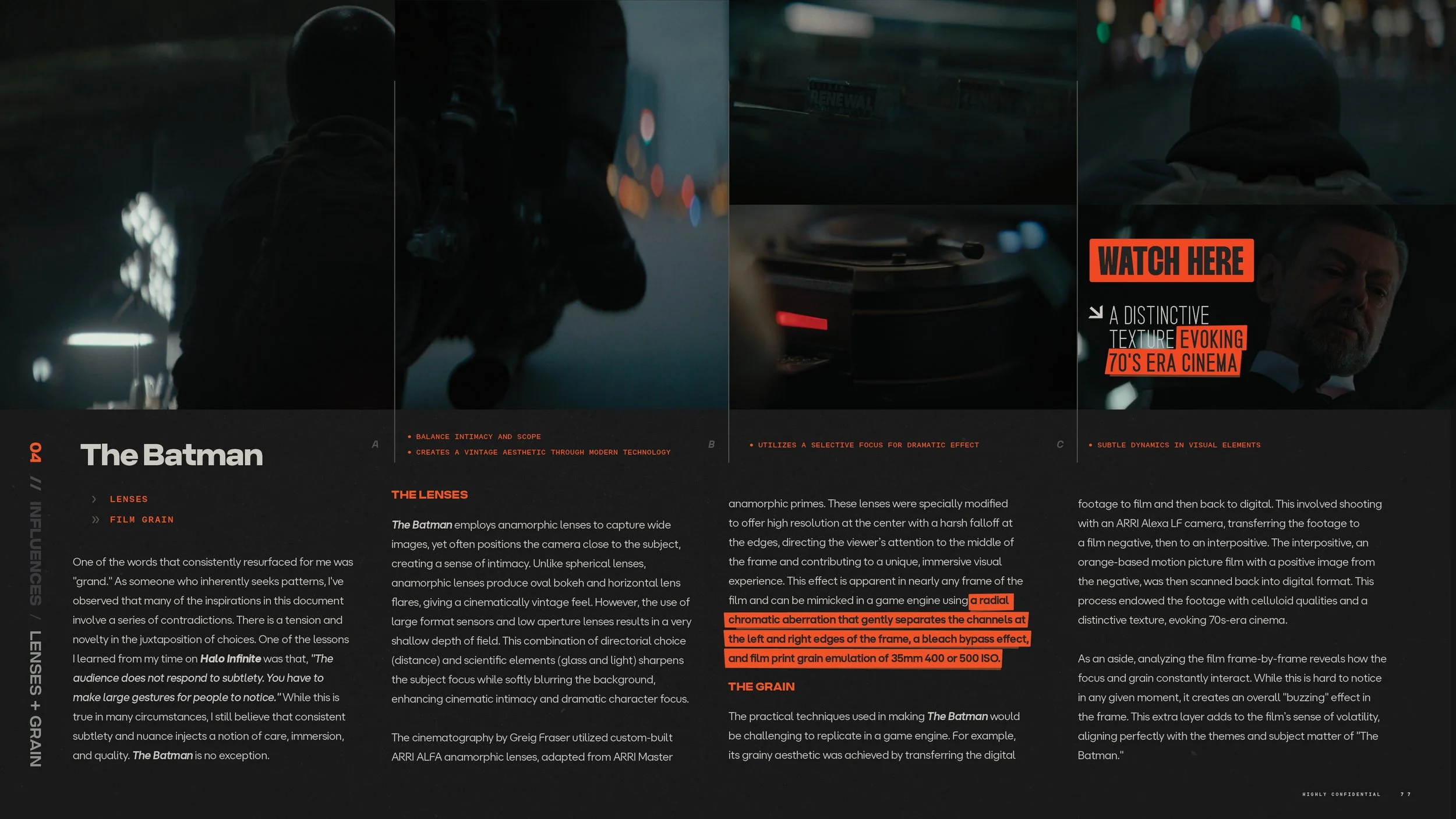

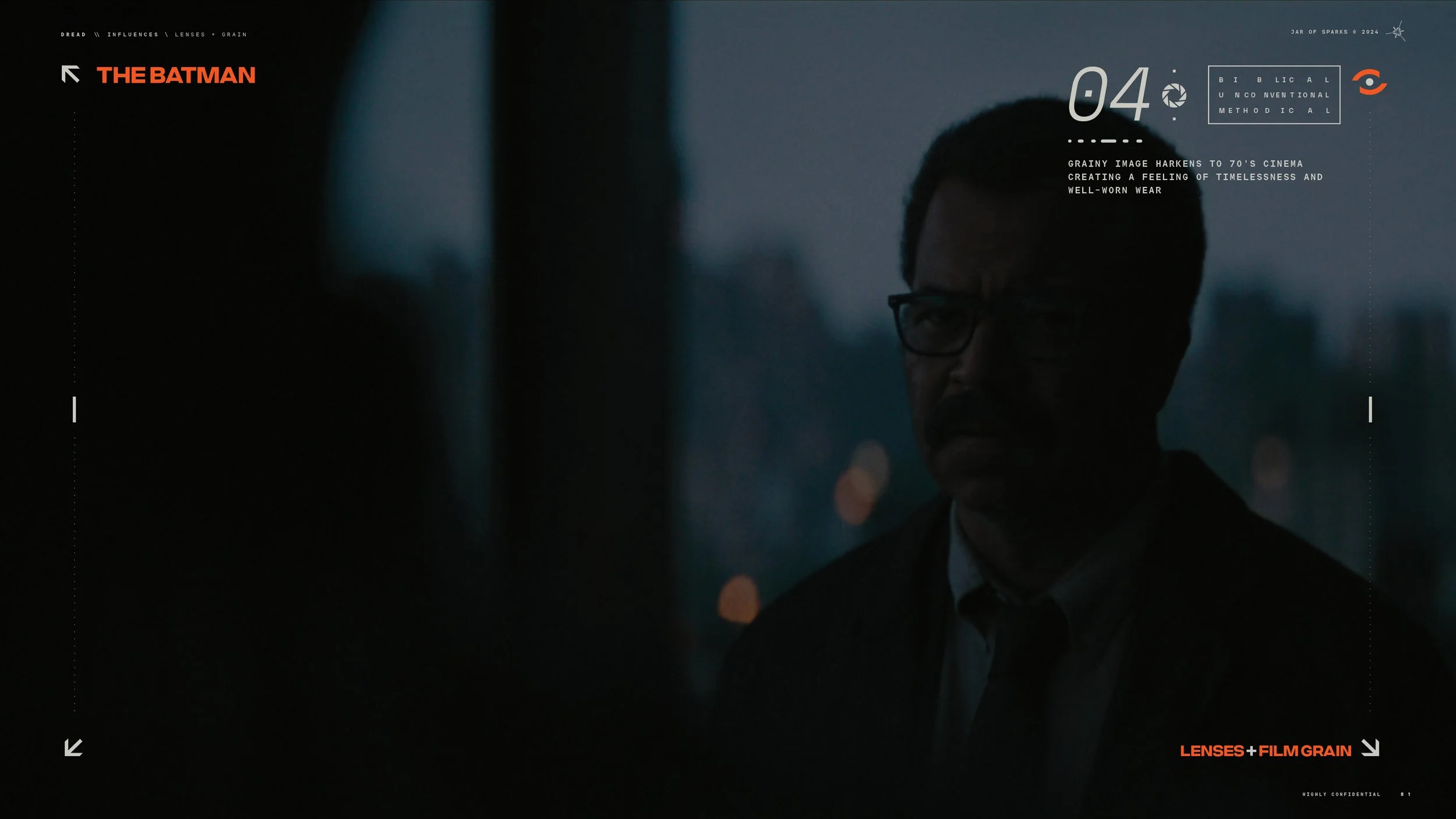

4. The Batman: Lenses & Grain

Balance intimacy and scope

Creates a vintage aesthetic through modern technology

Utilizes a selective focus for dramatic effect

Subtle dynamics in visual elements

Grainy image harkens to 70's cinema creating a feeling of timelessness and well-worn wear

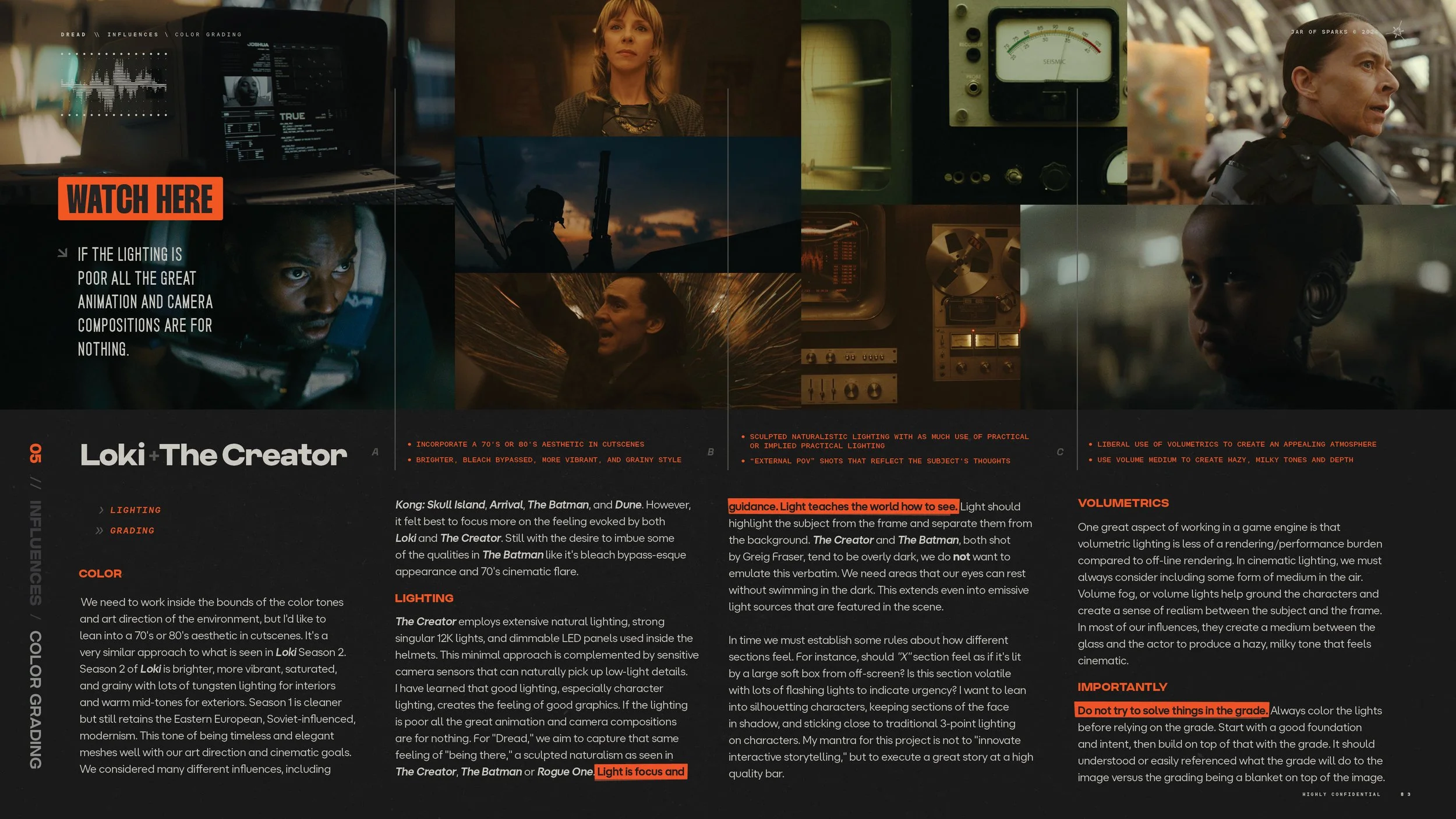

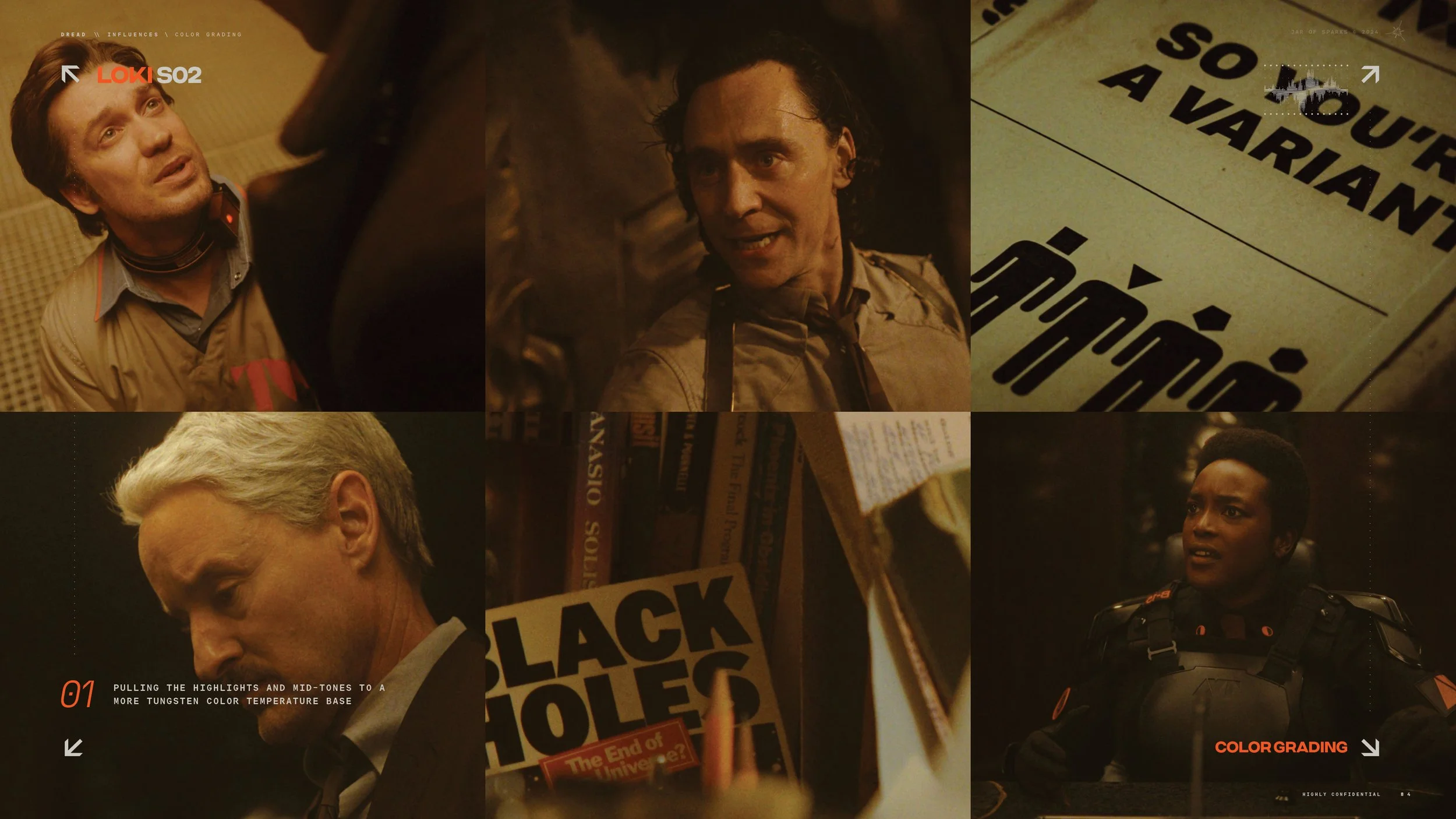

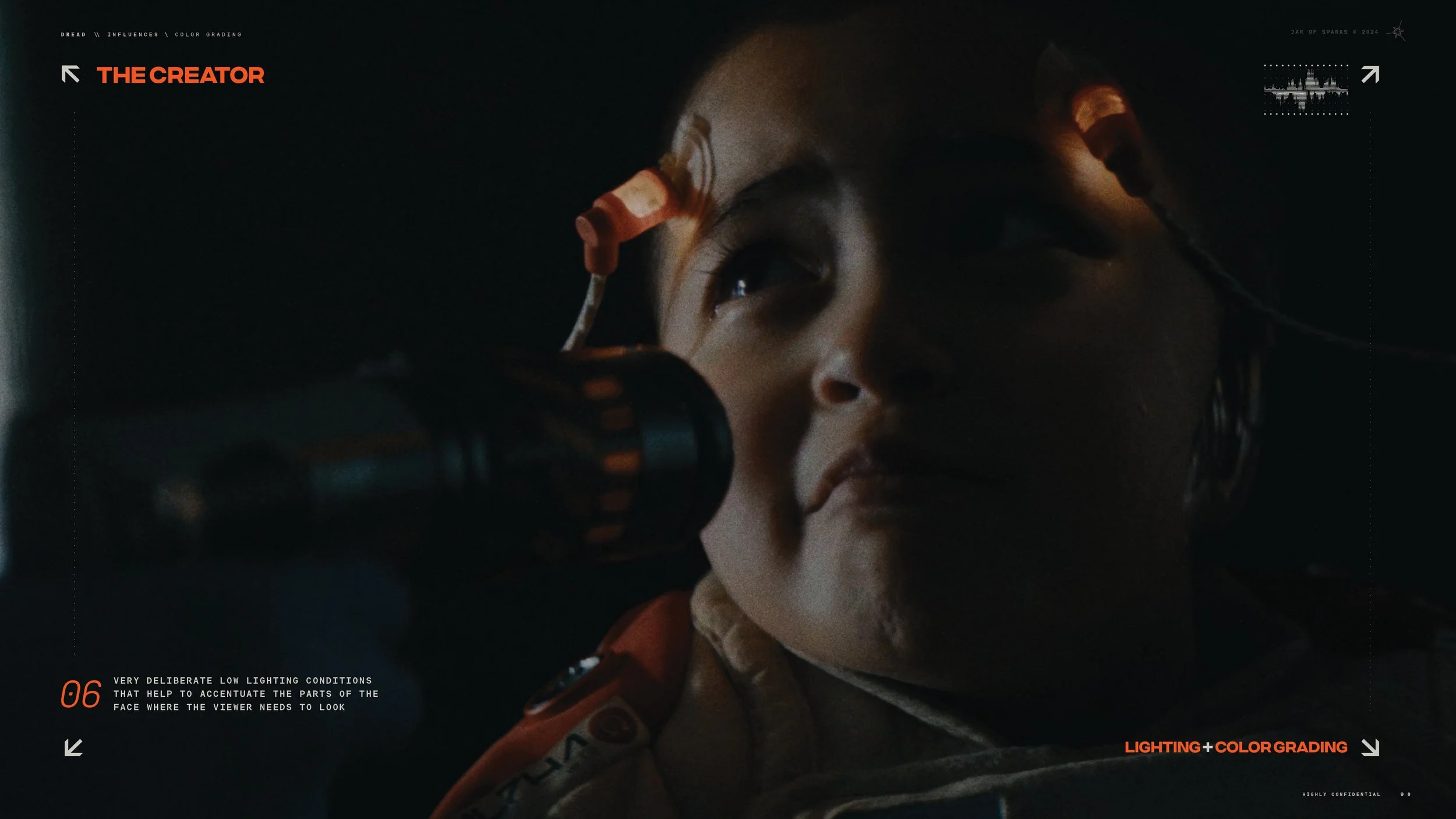

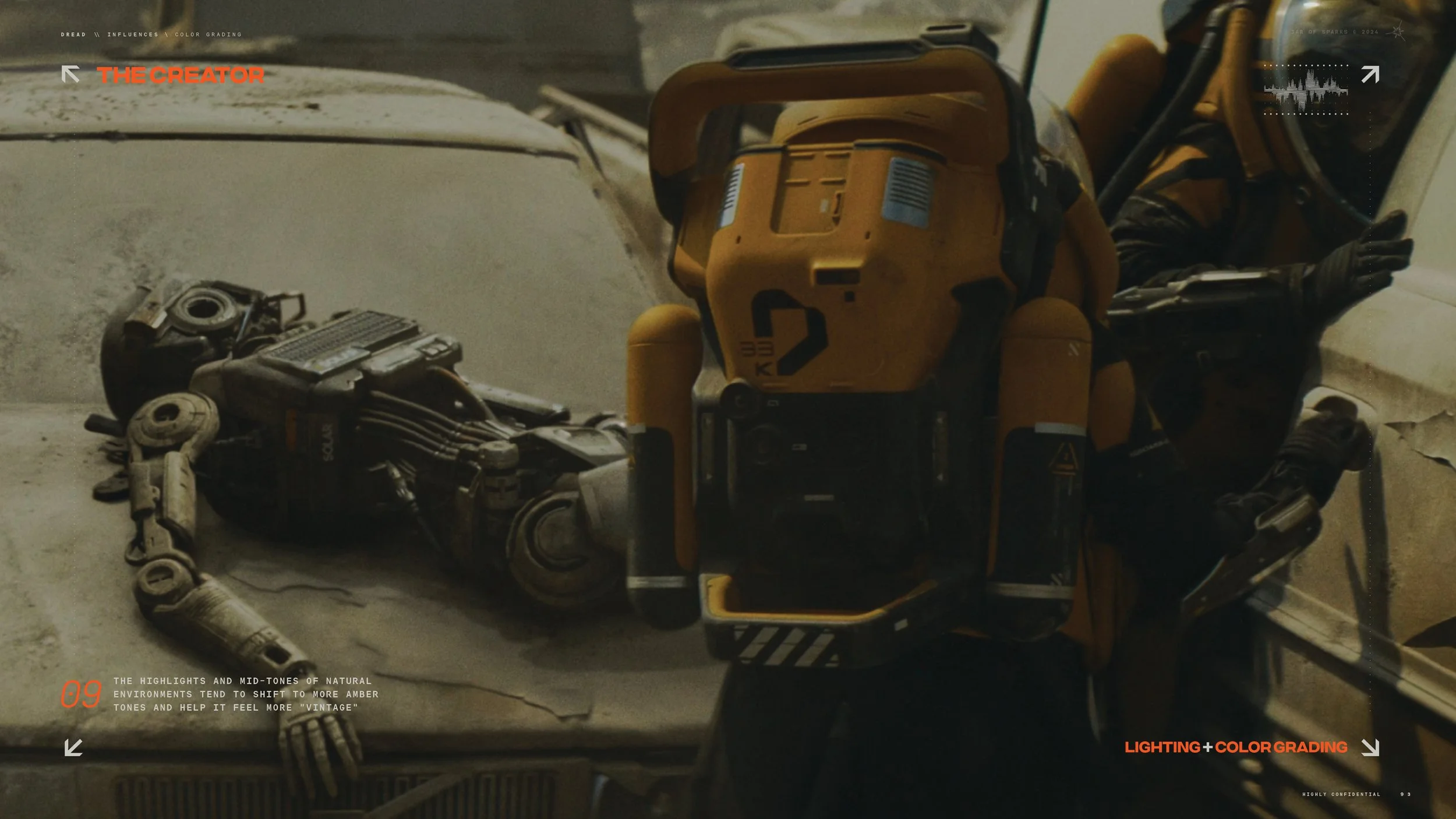

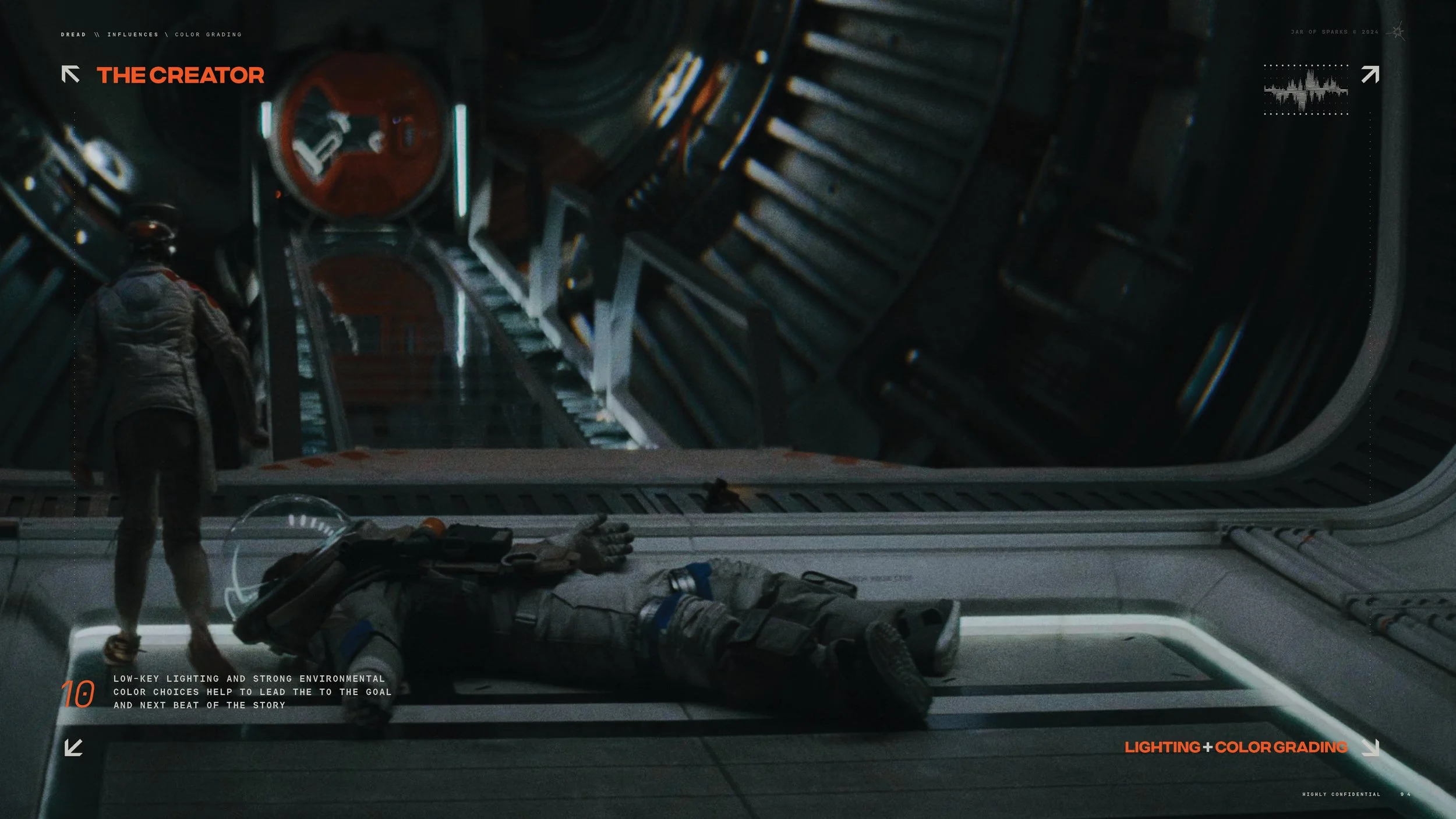

5. Loki + The Creator: Lighting & Grading

Incorporate a 70's or 80's aesthetic in cutscenes

Brighter, bleach bypassed, more vibrant, and grainy style

Sculpted naturalistic lighting with as much use of practical or implied practical lighting

“External pov” shots that reflect the subject's thoughts

Liberal use of volumetrics to create an appealing atmosphere

Use volume medium to create hazy, milky tones and depth

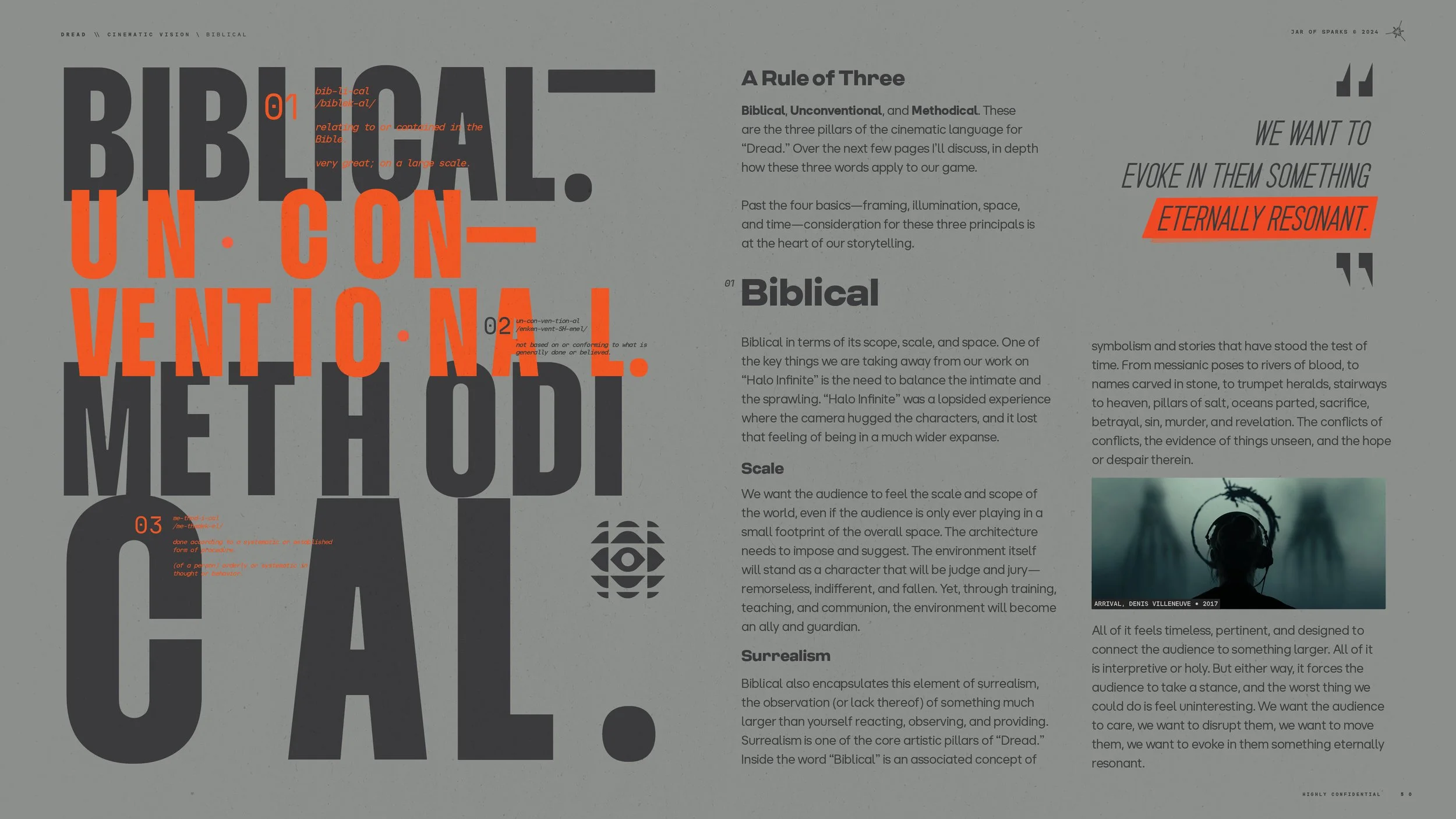

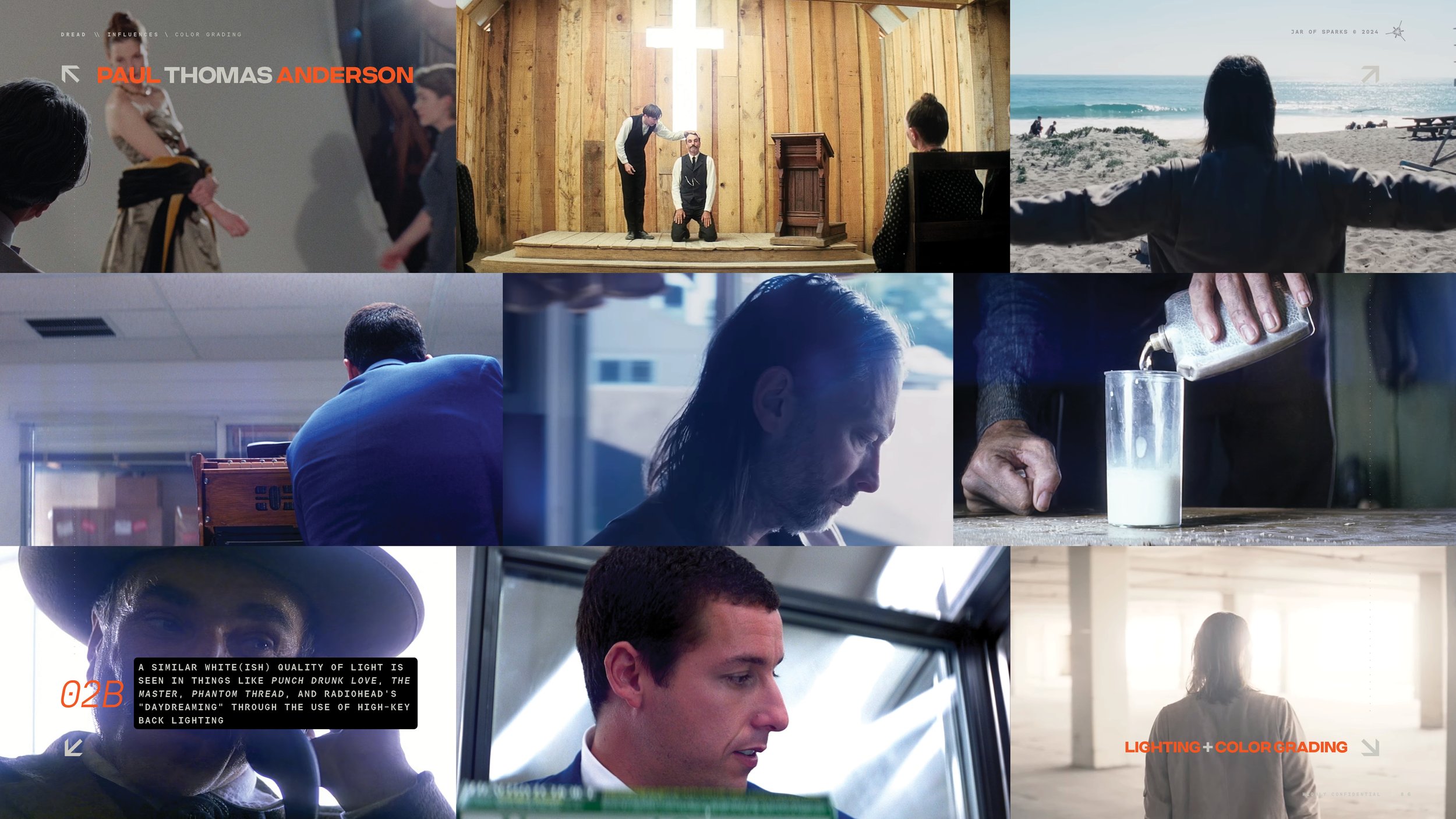

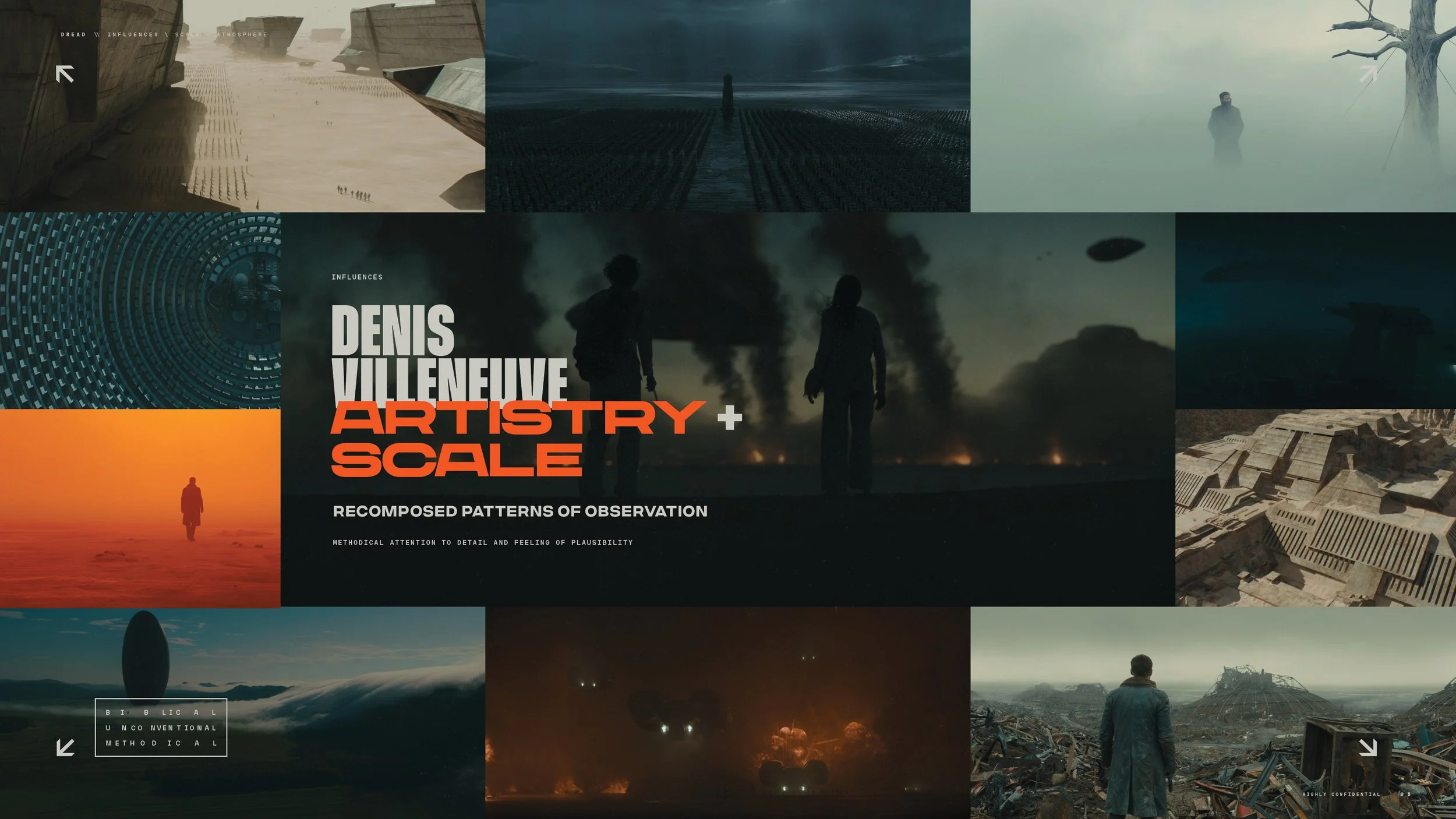

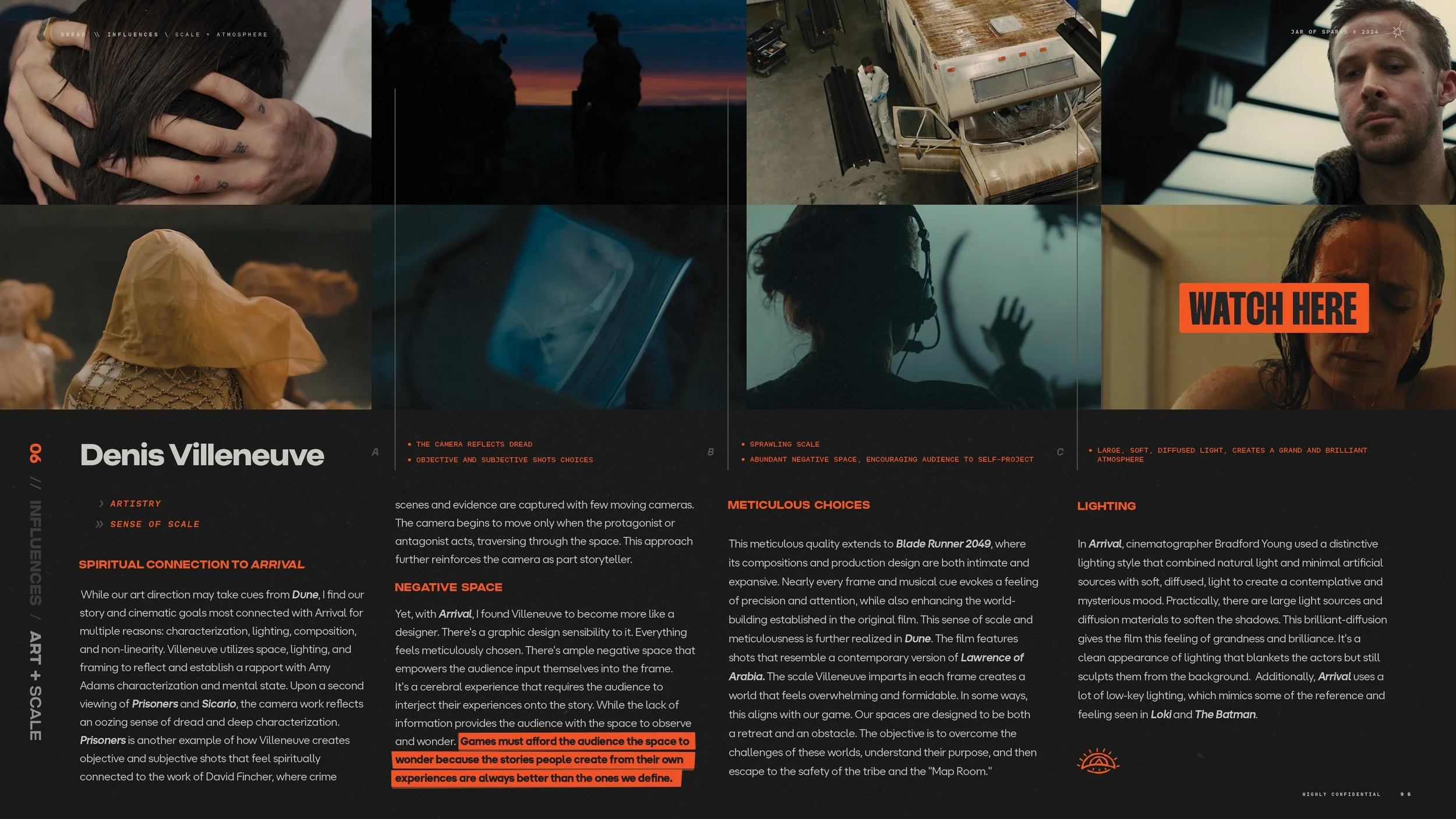

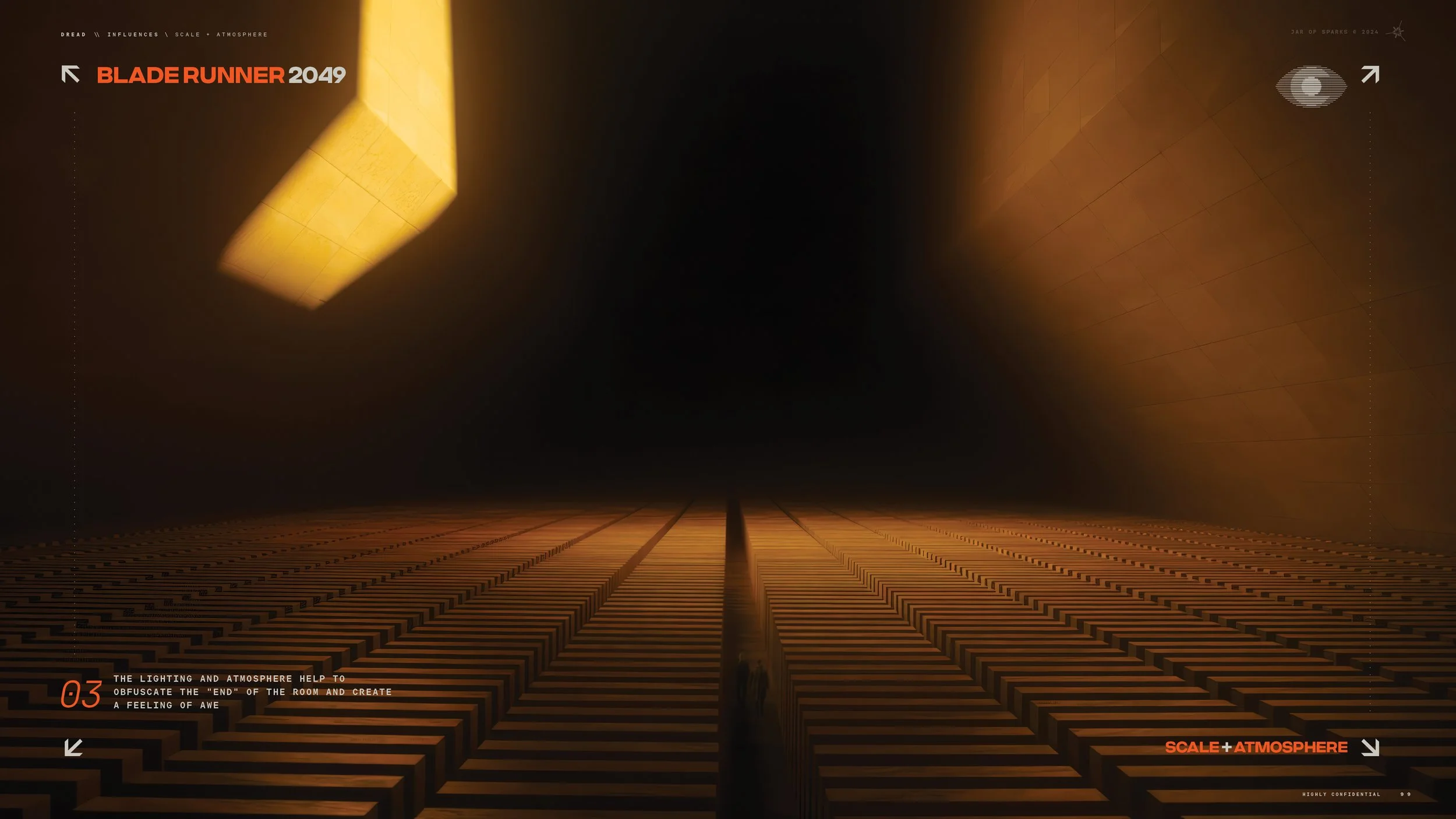

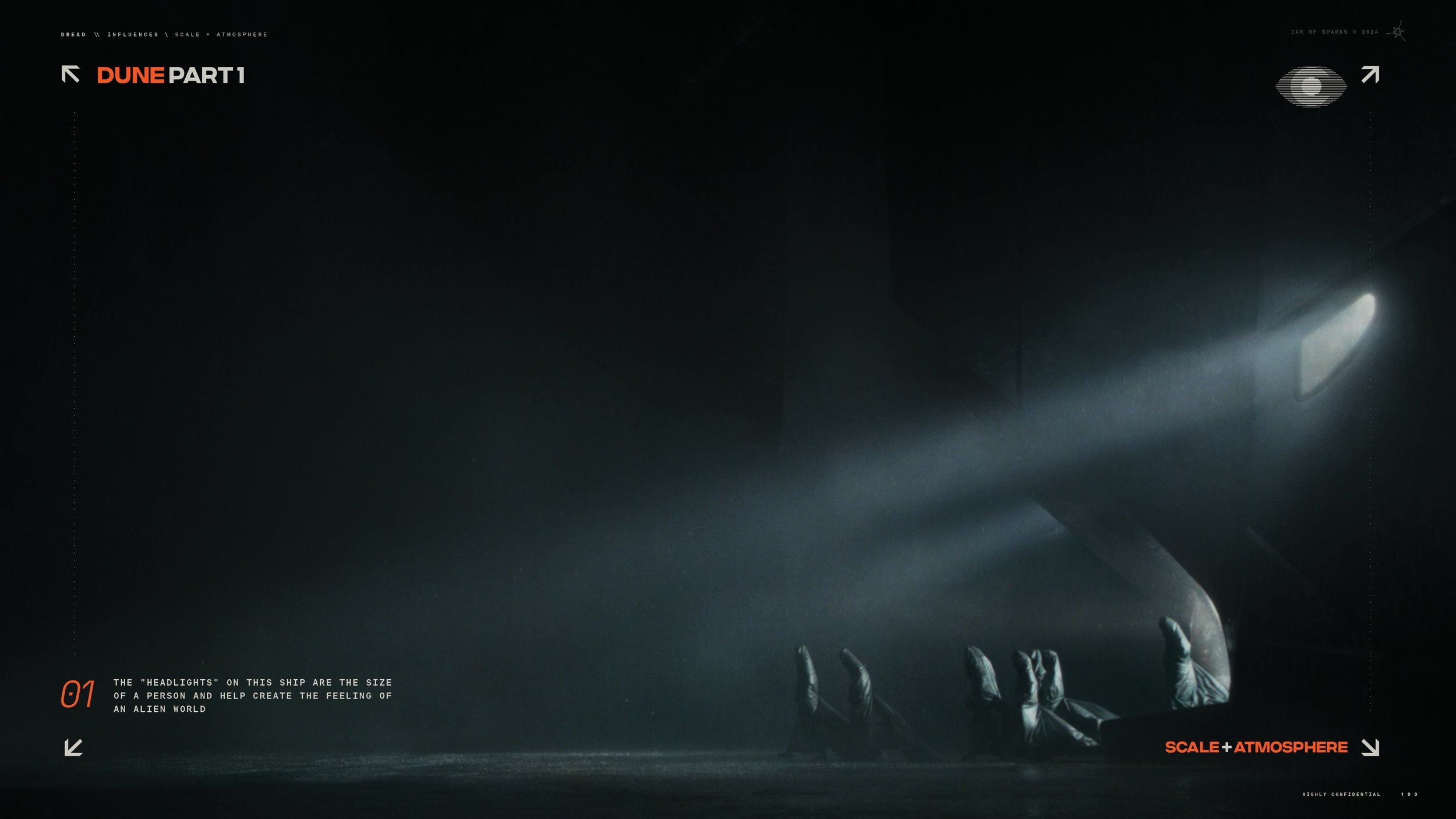

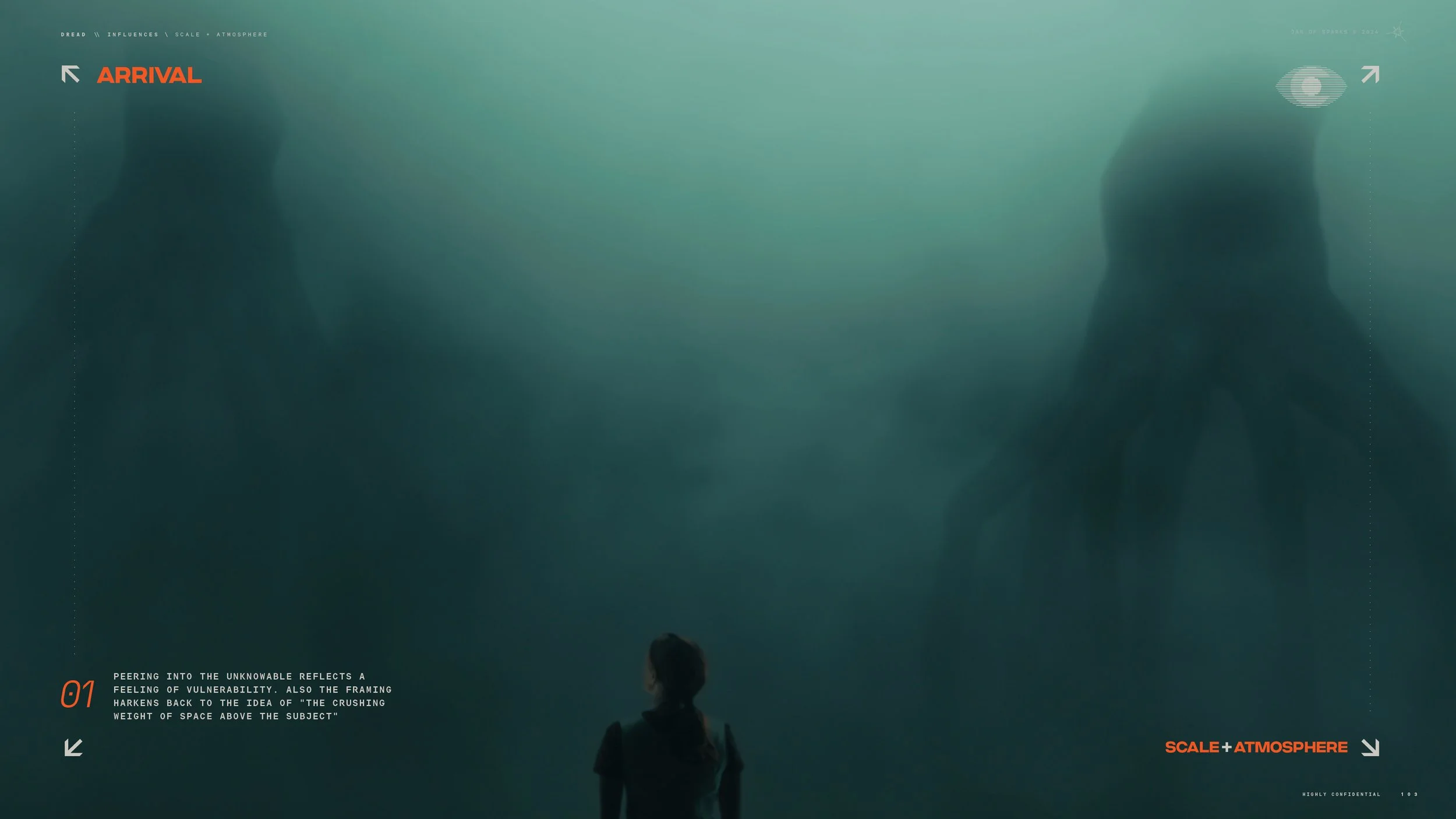

6. Denis Villeneuve: Art & Sense of Scale

The camera reflects dread

Objective and subjective shots choices

Sprawling scale

Abundant negative space, encouraging audience to self-project

Large, soft, diffused light, creates a grand and brilliant atmosphere

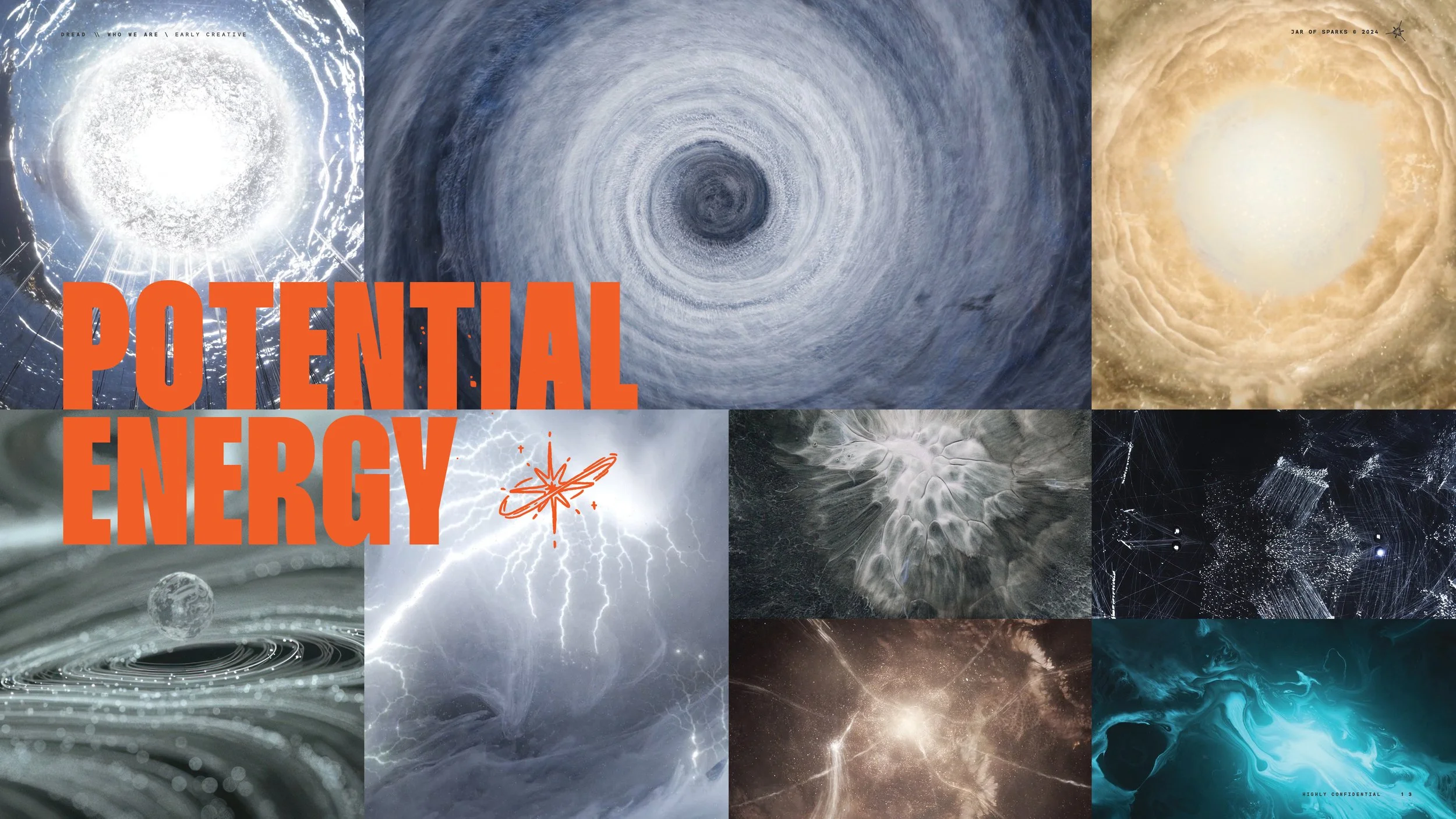

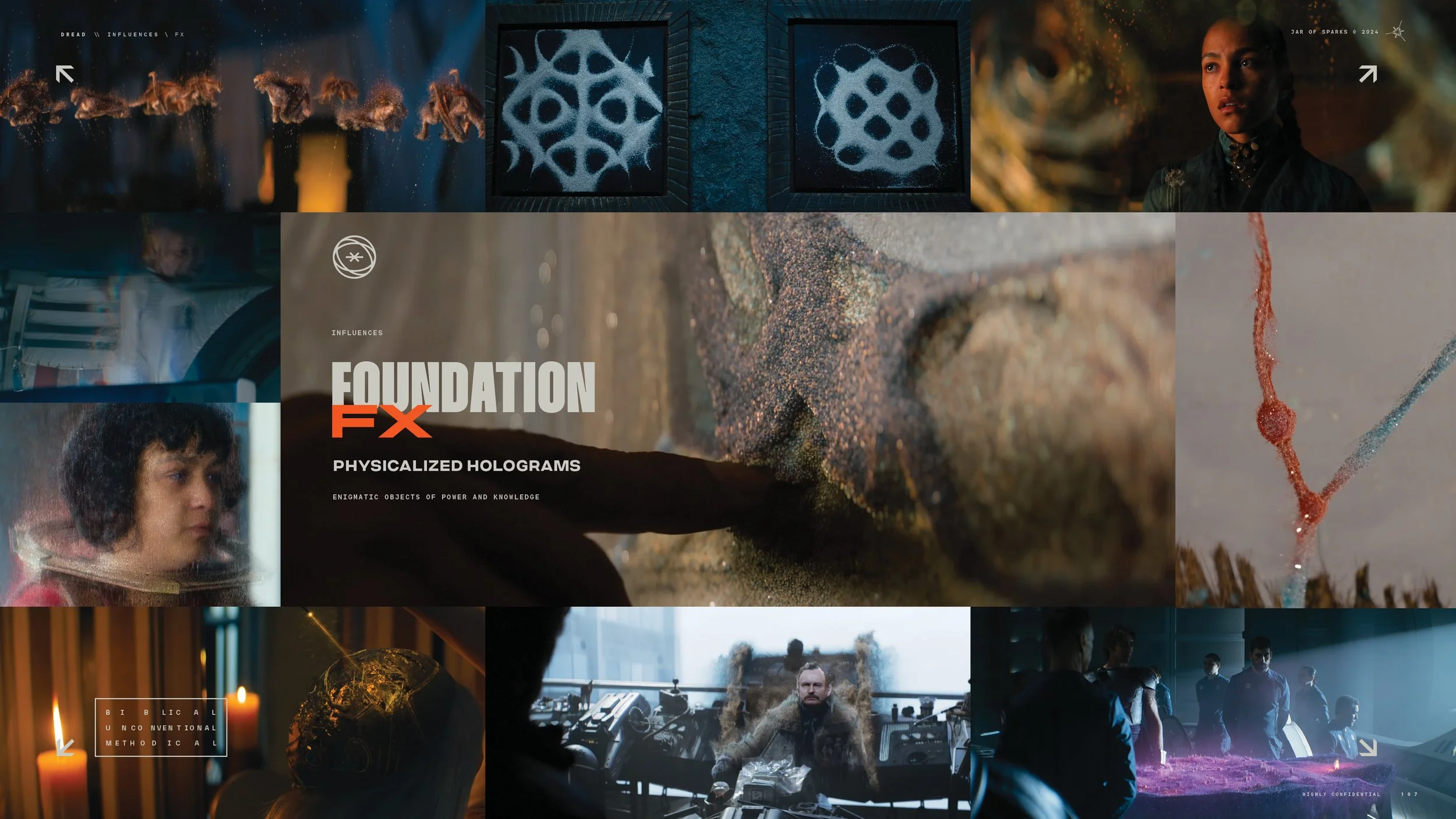

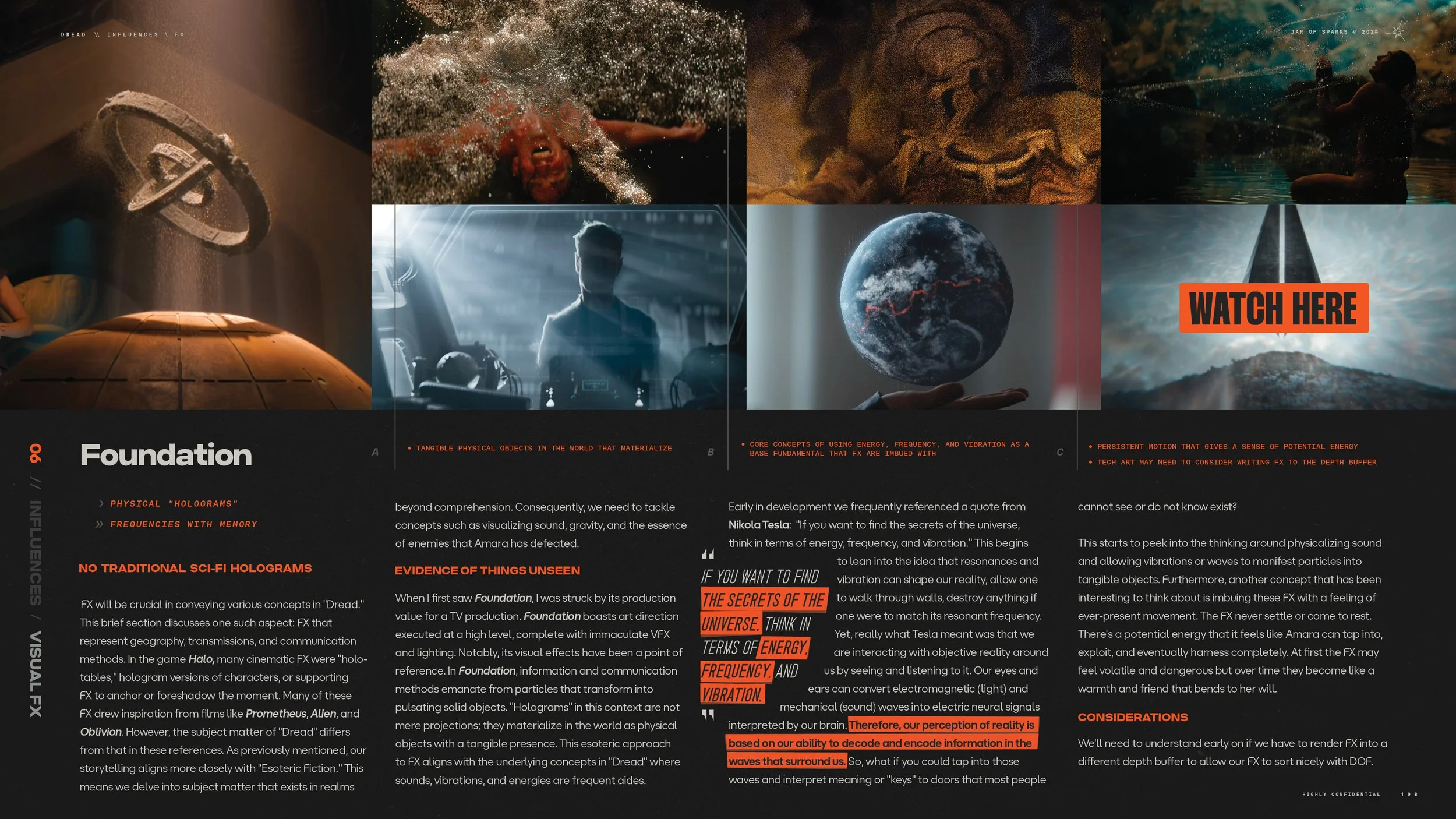

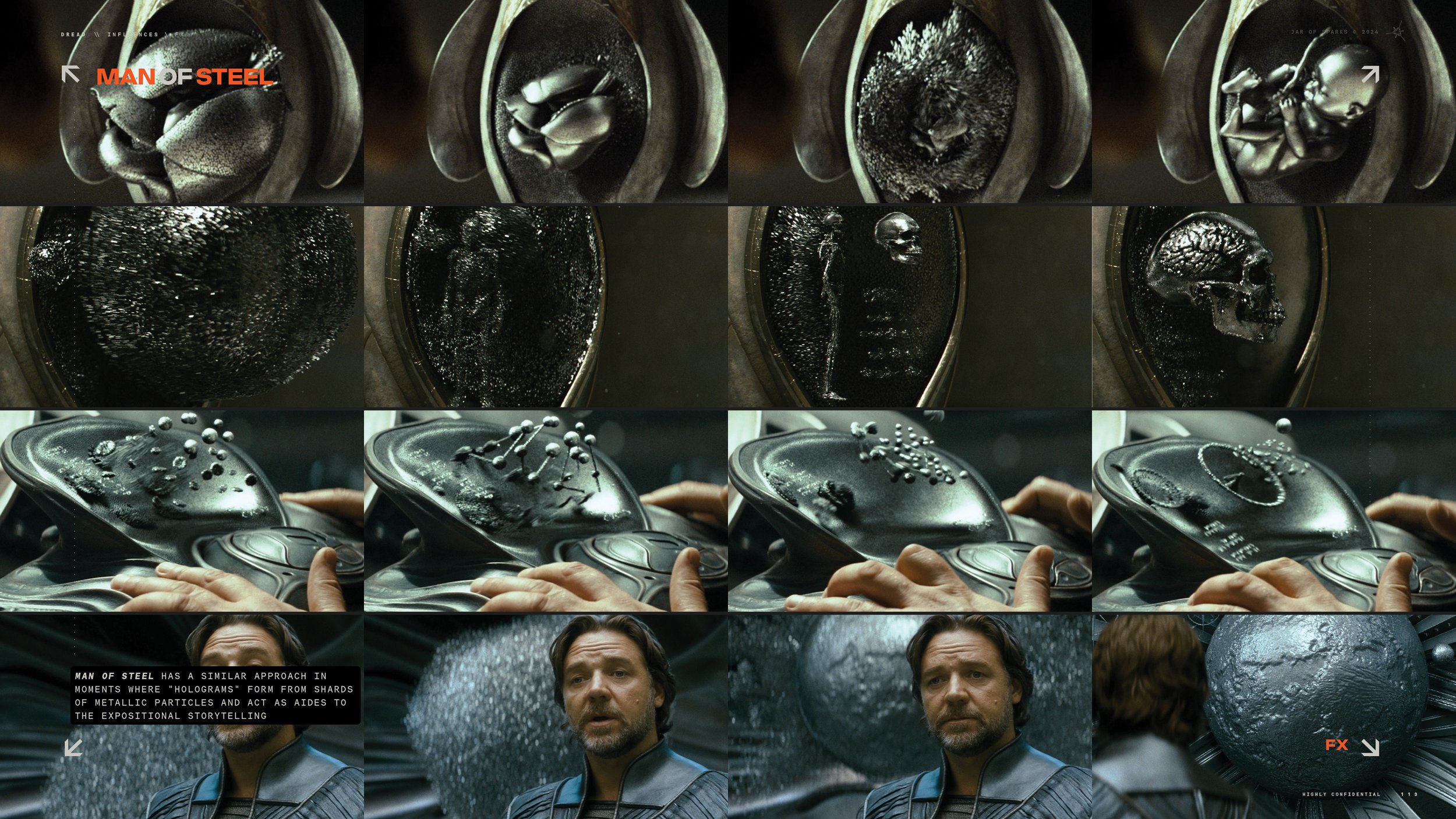

7. Foundation: FX

Physical "holograms"

Frequencies with memoryTangible physical objects in the world that materialize

Core concepts of using energy, frequency, and vibration as a base fundamental that fx are imbued with persistent motion that

gives a sense of potential energy

Tech art may need to consider writing fx to the depth buffer

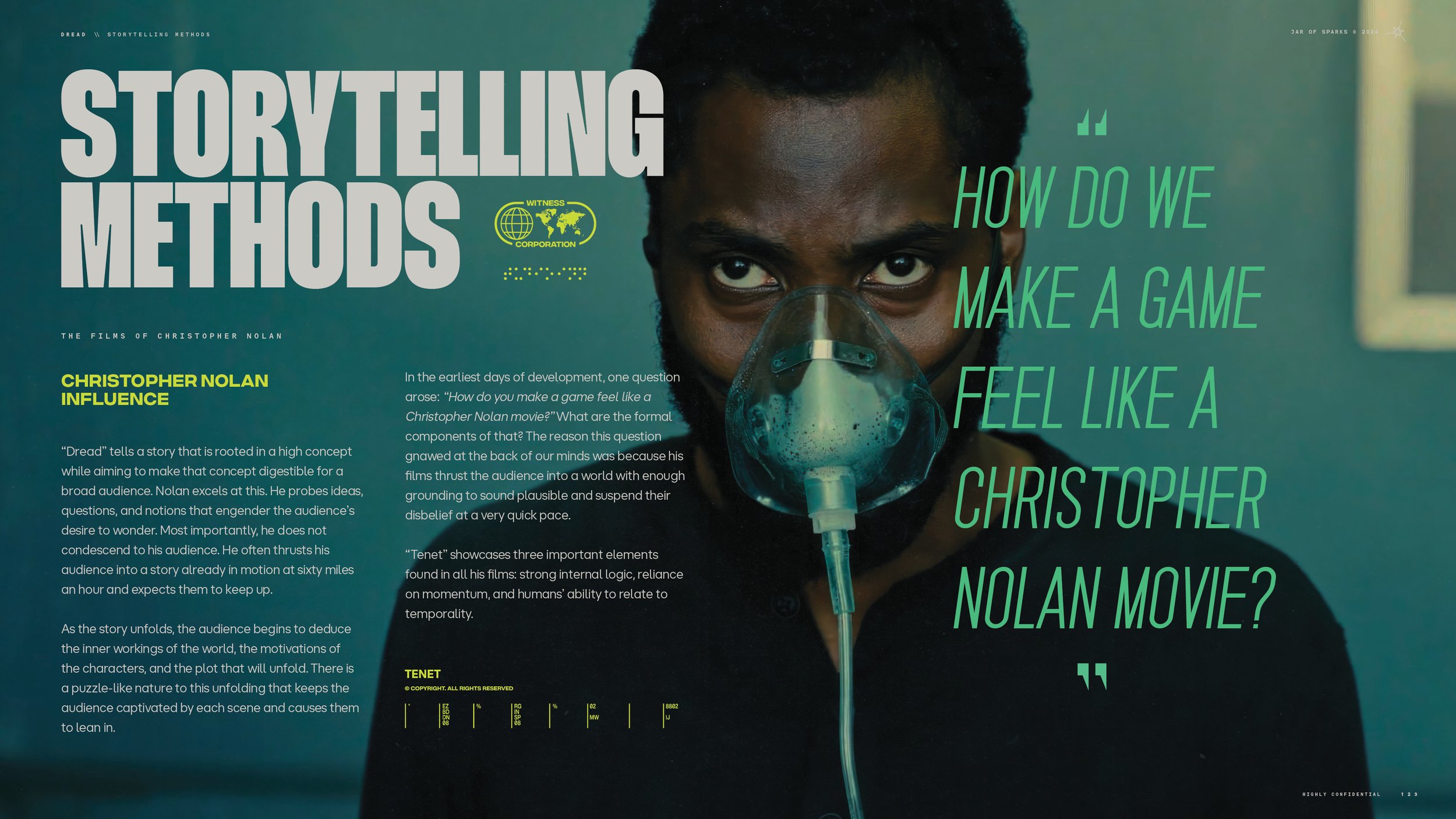

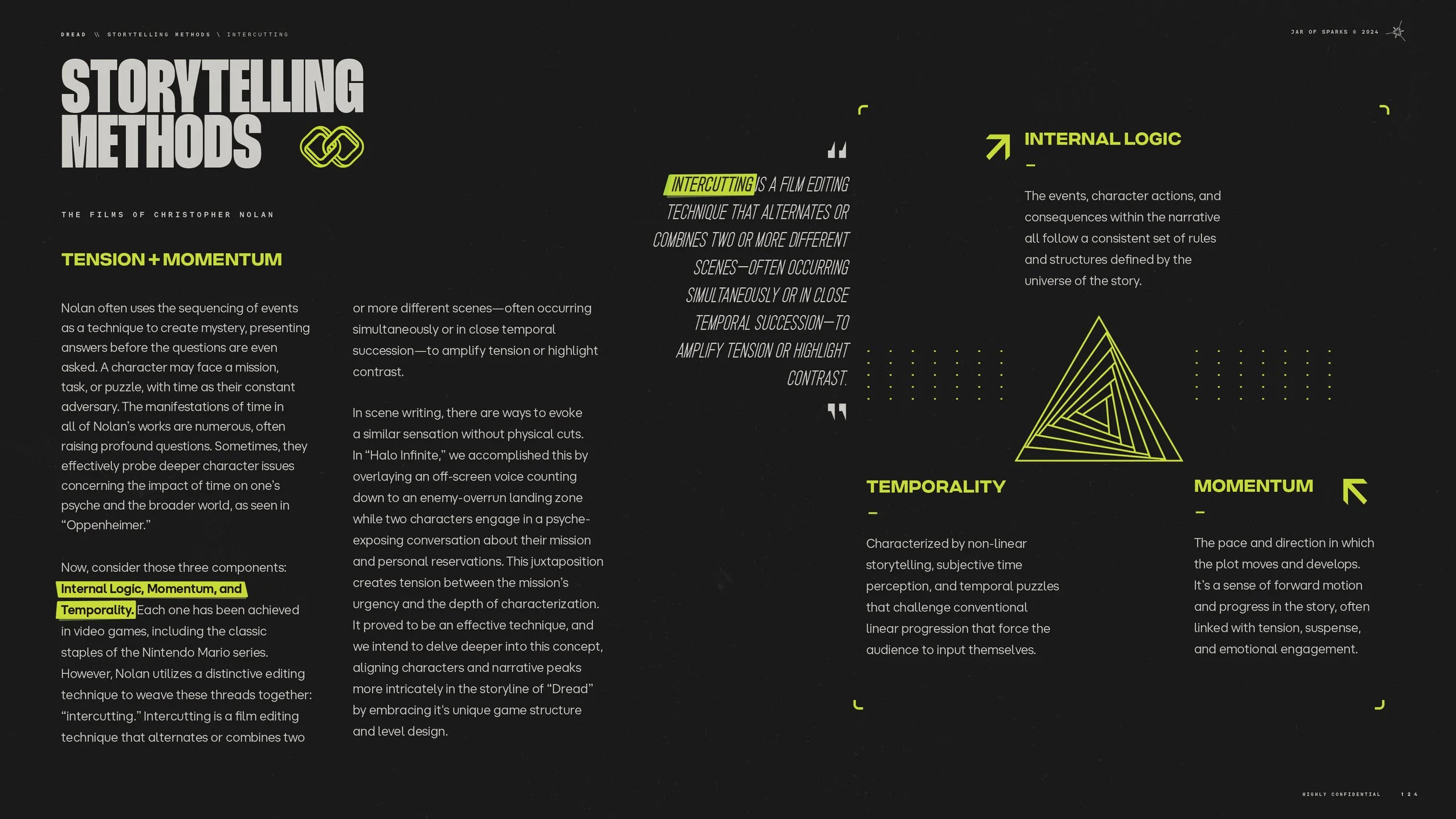

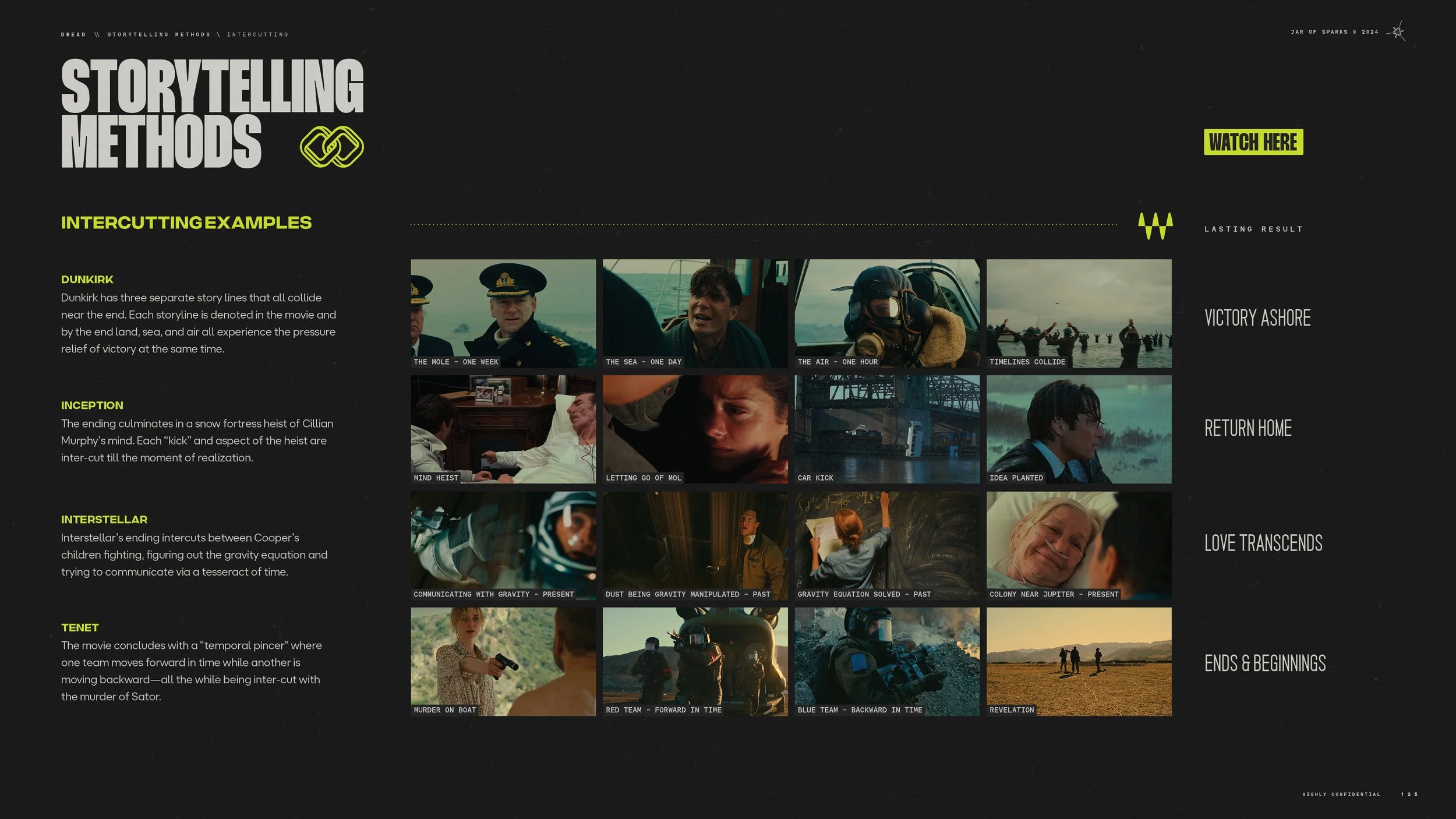

Christopher Nolan: High Concept Sensibility

Christopher Nolan's "High Concept Sensibility" is first because we believed early on that this is the type of story we would be telling. However, the need to balance "high concept" with action/adventure is continually at the forefront of our minds. One of the hardest things in games is to efficiently immerse the audience in a new world. As a player, you want to play the game. As a viewer, you want enough context to understand that the missions and objectives you are completing in the world have ramifications, stakes, and escalation. Nolan threads the needle on communicating enough of the "science" that it sounds familiar and enough of the emotional stakes that it feels resonant. We have the same charter of conveying enough plausible logic in a, experientially, foreign situation.

Depending on the type of game and the structure of the story, non-linearity can be a powerful tool, especially when trying to overcome the obstacle of "too much exposition" and creating characters that people care about.

We need enough information for the audience to want to dive deeper and enough grounding and humanity for the audience to identify with the characters. Both do not need to be front-loaded. Both can be by-products of conflict and resolution to engender the characters with feelings of heroism. Ideally, all of this occurs to propel the audience into a unique world and narrative atmosphere that suspends the audience's disbelief.

Mr. Robot: Framing

Mr. Robot uses unconventional framing throughout the entire series. When Mr. Robot came out in 2015 it immediately felt bold and unique. Its structure and screenplay do not talk down to the audience, do not hold back, and require the audience to think Notably, its framing was wholly unique. Mr. Robot's framing exemplifies that composition can signal and reinforce that something under the surface is stirring. Here is how we should apply the framing techniques seen in Mr. Robot to “Dread."

Vulnerability

Characters are frequently placed at the bottom corners of the frame, breaking the convention of being centered or adhering to the rule of thirds. Space above the character amplifies the feeling of vulnerability and reminds the viewer of the oppressive weight of space above them. This concept poses a persistent question to the audience and ties into the thematic underpinnings of cosmic horror, while also reminding the viewer of the oppressive weight placed upon Amara’s shoulders.

Power Dynamics

In scenes we want character to feel dominated by their environment or the entities that they are up against, and the visual representation of them being ‘down’ or ‘under’ is a subtle nod to this imbalance.

Paranoia & Perspective

Amara is often framed with foreground objects in the immediate space, through windows, doorways, or reflective surfaces. The use of such voyeuristic perspective suggests a constant observation and purposeful emotional distancing when in the HERE.

Negative Space

There’s an extensive use of negative space – large areas of the screen are often left empty, which can evoke feelings of isolation, disconnection, or significance of the surrounding environment. This can make the characters appear small, overwhelmed, or lost in their surroundings, which often reflects their internal state.

Direct Address & Symmetry

Characters are sometimes framed as if they are staring directly into the camera, creating an intimate and sometimes unsettling connection with the audience. This approach can break the fourth wall, drawing viewers directly into the characters’ world. While symmetrical shots and strong straight lines within the composition will guide the viewer’s eyes and often convey a sense of order amidst the chaos of our characters’ lives.

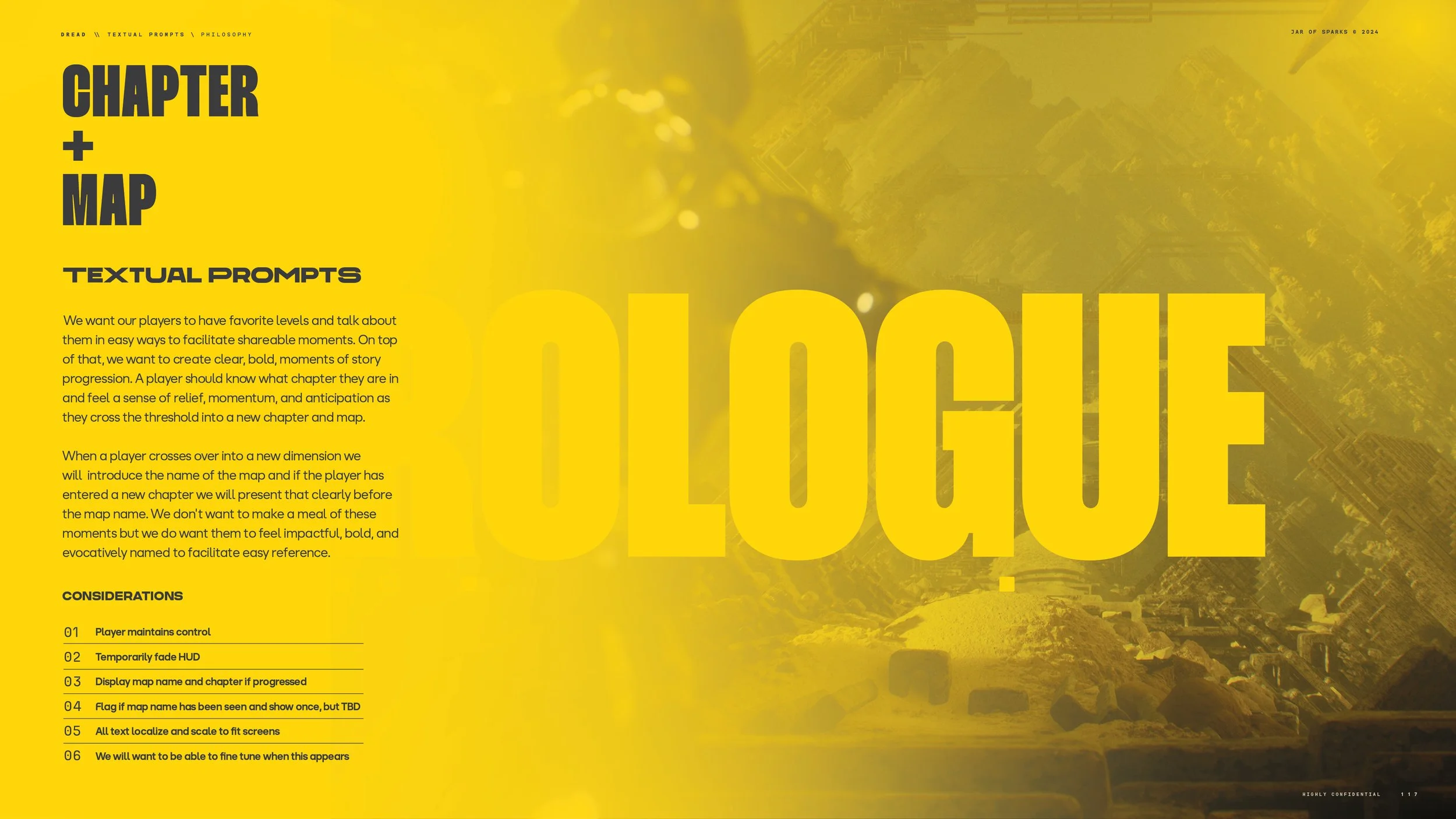

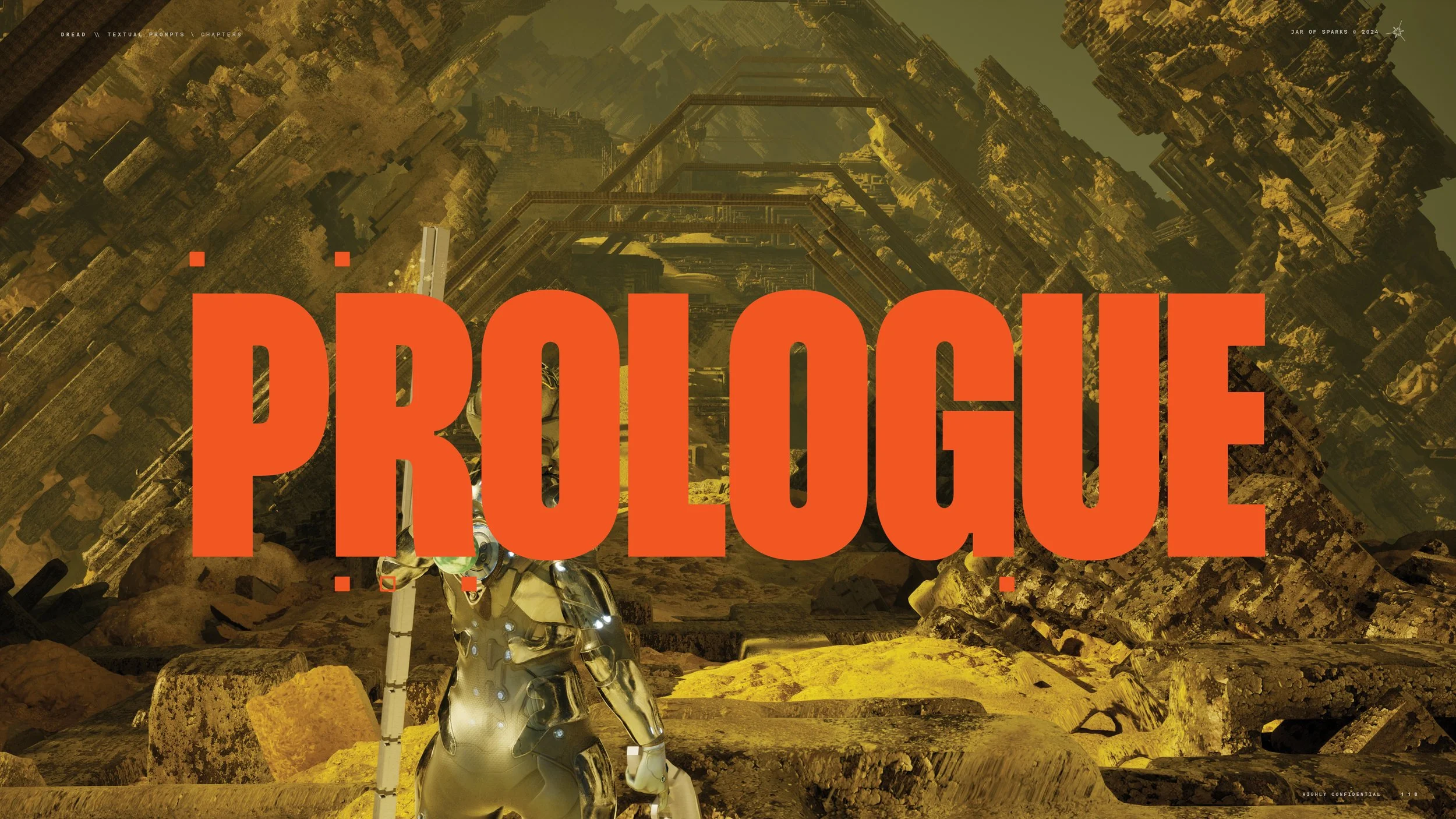

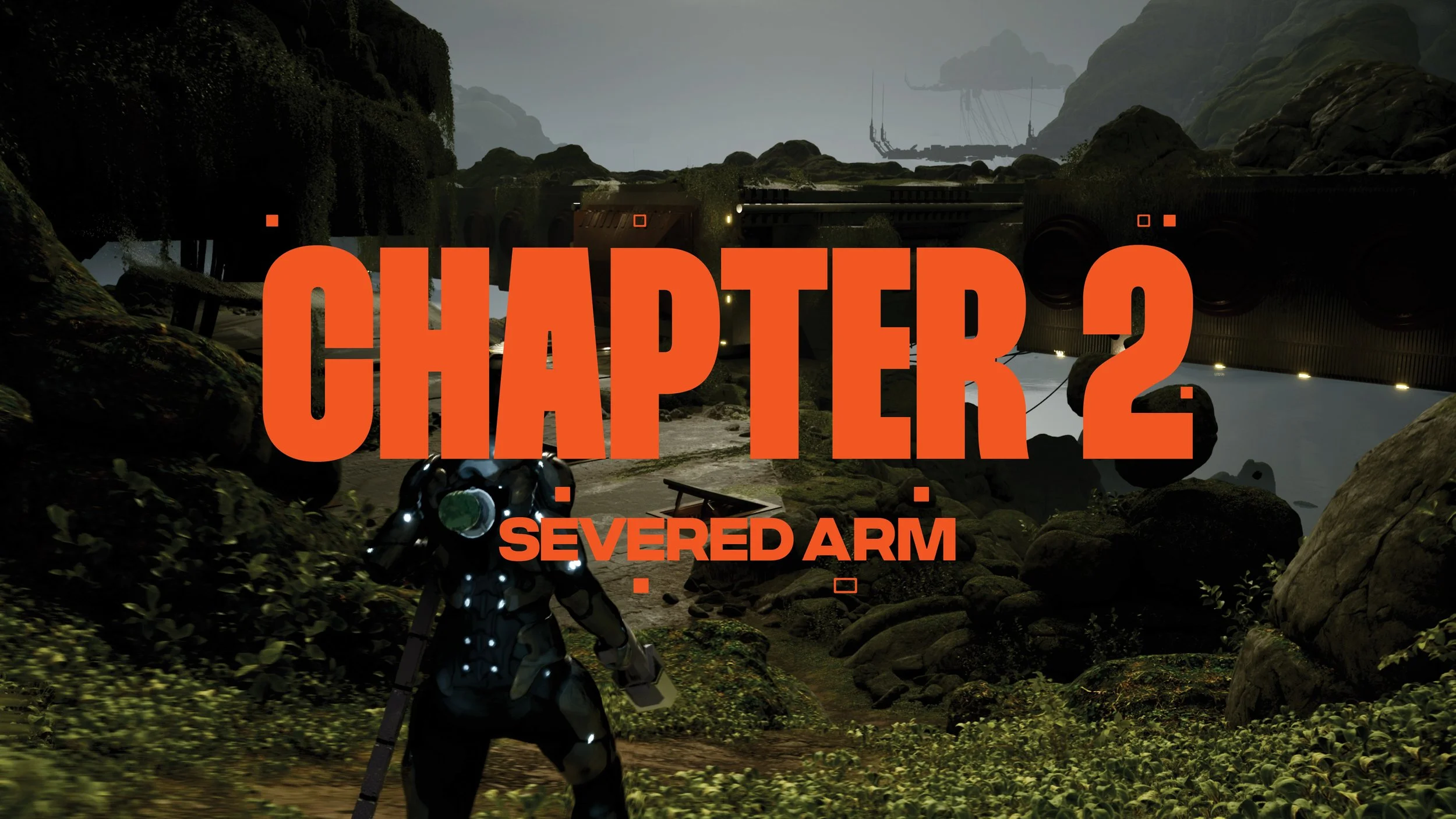

Game Experience

My primary role was to create the experience of the game. The Creative Director sets the boundaries for the experience. He’ll say what he wants the game to be, but it’s up to me to invent and congeal a lot of different ideas into the flow, pacing, and emotional beats of the game.

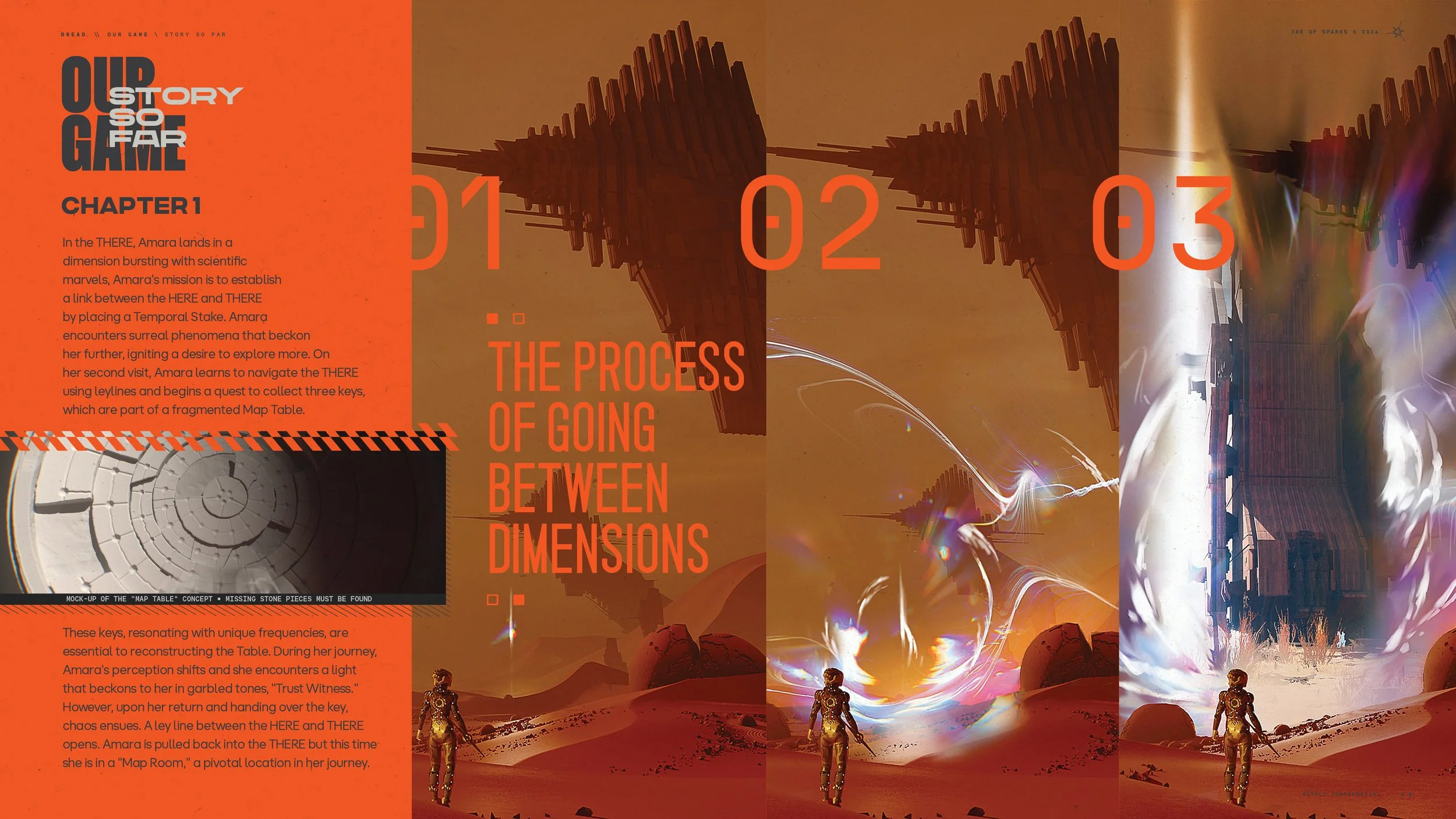

We used an internal tool called Confluence for documentation. That documentation is here as embedded PDFs. The game was split into chapters. There are two chapters listed here. The first chapter was created about 6 months after Chapter 2. Chapter 2 was our original vertical slice goal. This however, was changed after a milestone review where NetEase wanted the game to have a different progression model. Therefore, work on that Chapter was halted. The levels were intact but the flow and story beats needed to be put on pause. NetEase also did not want us spending money on cinematic storytelling at this time. We had to be as cost effective as possible since we were not in full production. The budget we had was to be used to get the primary gameplay and environments up and running. Once that worked we’d then flesh out sound design, cinematics, and VO.

Creating the Experience

This documentation would be created by partnering with the Gameplay Director and the Art Director. Then I’d constantly be reviewing the progress of this documentation and ideas with the Creative Director. The Art Director would help me set the boundaries of the type of architecture and biomes that would fit the experience and create enough feeling of differentiation. This way of working was incredibly successful because nothing was done in a vaccumm. The ideation process was done with the Art Director therefore nothing was a surprise and he could vet and approve if he had the manpower to get these experiences over the finish line in the allotted time.

The Gameplay Director and I would talk about the ideas that he was trying to accomplish in the time period and the things his team needed to prove. This meant that the experience was supporting the team’s goals. A lot of what the experience needed from the Gameplay Director was the types of enemies, the metrics of those enemies, how the effects of defeating certain bosses would aid in the player’s movement set. Therefore, since I also was the director of the levels this knowledge dovetailed into the levels. It was a challenge to create levels for this game because there’s a tension between the art and the need to continually adjust metrics based upon experimentation with Augments (or Mimics). The mimics would completely the change the movement set of the player and grant them the ability to walk on walls, destroy walls, fly over walls. That meant that we needed to understand the basic metrics as fast as possible.

Everything needed to move and hit very prescribed deadlines to keep the project on track and show progress to NetEase. Fortunately, this and other documents were the key any time the studio had to pivot. And we pivoted a lot.

Prove then Expand

Everything we were doing was taking a model dubbed, “Prove then expand.” This meant that we had to get the basic game structure and mechanics right. Then expand and layer on levels of polish to everything. This way of working created a scenario where levels were created in very rudimentary states but everything we wanted to do would be marked up in the level itself.

Therefore, if we wanted a ‘vignette’ to introduce an enemy a cube and text would indicate the moment. If we had a cinematic moment, we’d place a sequencer file with text that would state what the cinematic is doing. If that cinematic granted the player some kind new mechanics, such as being able to rotate the rings on the map table, the player would gain that ability post-cinematic and a text prompt would indicate that this ability has been unlocked.

The goal was to create as much as the game experience as possible, as quickly as possible. Therefore, the team, and executives could access our build at any time and understand the rough outline of the game—inside the game itself. We always wanted everything we were doing to be in-game as fast as possible. We’d often say if it’s not in the game it doesn’t exist. However, my job was to outline what the game needed to be. Therefore, 95% of my work was outside the game directing the work for level designers, artists, and gameplay animators to include in the game.

The studio head always need to be a year ahead of its directors and its directors need to be a quarter ahead of its leads. Therefore, it’s my job to be selling the vision of where the game needs to go along with the other directors. These documents show some of that work that acts as a blueprint for the game’s experience.

Dread: Level Experience Feedback

We didn’t even have an official level designer yet. This was designed by an Environment Artist named Ryan Roth. This was one method for ad-hoc feedback when most of the studio was remote. Later in development these all became meetings with a producer in tow.

MAP DESIGN

When designing maps, the size and initial placement of state-dependent objects are essential for creating moments of chance. The experience is truly driven by the collision of player abilities, team composition, dimension, and map state variables, resulting in the game’s philosophy, “TACTICAL CHAOS MANAGEMENT.”

Additionally, the game introduces consequences for being too slow in achieving objectives. This creates a constant urge to move forward quickly to reach the objective, while the ‘state’ of the map pulls players toward exploring more—at either their benefit or detriment. These dilemmas become pivotal moments that can aid or hinder the squad, maximize individual power, or accelerate progress toward the objective.

MAP DESIGN RULES

-

Every map needs multiple possible insertion points that can be randomized.

a. Rules to the amount of portals in a given map is based on map size.

b. Each portal needs to support the Diving Bell and its repair.

-

Objects on the maps can be moved based upon rules given to the object. For example, unused portal locations

in each run can be populated with unique objects to encourage exploration.

-

Every map needs at least one clear and distinct landmark to help situate the player in the world.

-

If making an interior space, an exterior space must be adjacent to it to accommodate the Diving Bell.

-

Every map needs a shortcut that can be accessed off the beaten path that makes the journey back more direct.

-

Spaces must be constrained in their size or length to facilitate around 10 minutes of play-time per dimension.

However, spaces must be spacious and flexible enough to accommodate multiple players with a litany of mimics and enemies of varying shapes and size.

-

We are making a systematic game. It is not the level designer’s job to “refine” combat or create one-off solutions.

Objects or triggers must work in every dimension and be easy to replicate, swap, and control.

-

If something is hard to do or repeatedly takes a long time, we must engage engineering or tech art to assist in bringing down that time to focus on the creative endeavor the audience will remember.